On March 13, 2025, Taiwan’s president Lai Ching-te declared that China was a “foreign hostile force” exploiting Taiwan’s freedoms to “divide, destroy, and subvert us from within” and introduced 17 major strategies to respond to threats from China against Taiwan. Four days later, on March 17, 2025, the Chinese Ministry of State Security (MSS), posting on its public account on Chinese messaging app WeChat, named four Taiwan citizens who allegedly are members of Taiwan’s Information, Communications and Electronic Force Command (ICEFCOM, 國防部资通电軍指揮部)1 “linked to ‘Taiwan independence forces’.” On the same day, three Chinese information security companies, Qi An Xin, Antiy, and DBAPPSecurity (a.k.a. Anheng Information), simultaneously published reports on alleged Taiwan-linked APT group PoisonVine (毒云藤)2 (a.k.a APT-C-01, GreenSpot (绿斑), APT-Q-20). Evidently, this was a coordinated action led by the MSS.

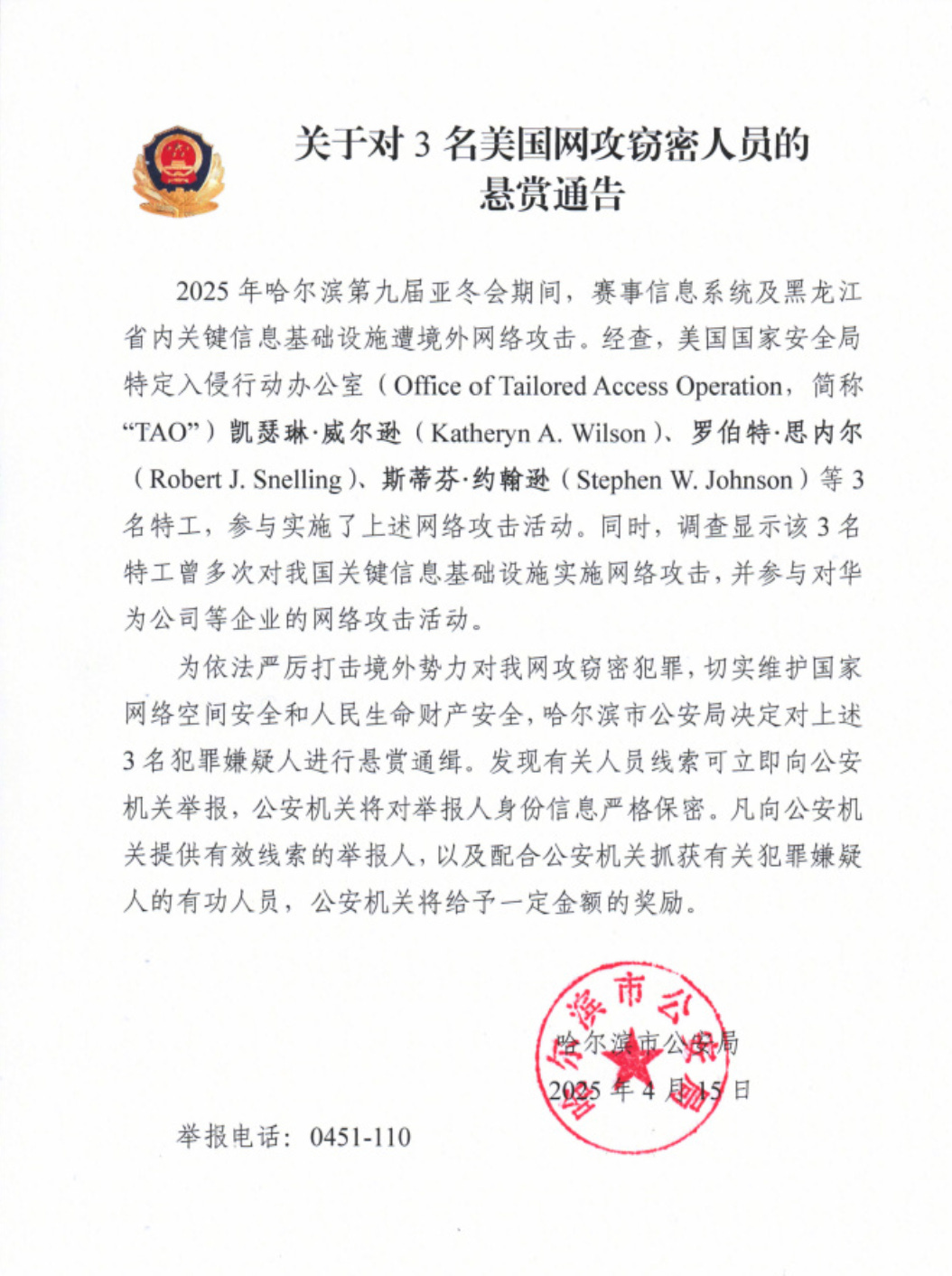

Nearly a month later, on April 15, 2025, the Harbin Public Security Bureau—a regional office of the Ministry of Public Security (MPS)—escalated the attribution campaign further. In a statement posted on the Chinese social media platform Weibo, it named three individuals alleged to be operatives of the Tailored Access Operations (TAO) unit of the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA). The statement accused them of conducting cyberattacks during the 9th Asian Winter Games, held in Harbin in February, and of “repeatedly” targeting Chinese telecommunications company Huawei and other domestic firms. It also stated that “monetary rewards will be granted to those who provide effective clues to the public security authorities or those who assist the public security authorities in the capture of the suspects.”

The Natto Team’s previous research indicates that public cyber attribution and a “name-and-shame” strategy are a relatively new foreign policy tool for the Chinese government. Using this new foreign policy tool on Taiwan is new as well, particularly the claim that Taiwanese hackers are targeting China with the goal of asserting Taiwan’s independence. The outing of alleged U.S. operatives represents yet another escalation in China’s evolving approach. Many Chinese social media posts commented on the MSS announcement on Taiwan. One wrote, “mainland China and Taiwan are engaging in a war without gun smoke in cyberspace now.” This saying seems very vivid, but in reality, it describes the situation closely.

China Using Public Cyber Attribution: A Short History

In September 2023, Natto Team published research showing that China’s use of public cyber attribution initially focused on calling out alleged US government-backed hacking activities. Furthermore, it evolved from cybersecurity company-centered public attribution, starting in 2019, to an explicitly government-led public attribution with the cooperation of cybersecurity companies since September 2022. Within the Chinese government, at first the National Computer Virus Emergency Response Center (CVERC) took the lead in initiating public cyber attribution. Later, multiple agencies, particularly the Ministry of State Security (MSS), also began issuing such reports. China has increased the intensity and pace of public cyber attribution since 2023. After the CVERC’s first report, in September 2022, alleging that the US National Security Agency (NSA) had launched a cyber attack against China’s Northwestern Polytechnical University, Chinese government agencies working with Chinese cybersecurity firms have called out alleged US hacking activities at least four times in 2023.

In 2024, the Natto Team discovered that China’s use of public cyber attribution has gone to another level in the Volt Typhoon case. When the United States and the so-called Five Eyes countries raised the alarm about Chinese state-sponsored cyber actor Volt Typhoon targeting US critical infrastructure, China’s CVERC published a report in April 2024 arguing that Volt Typhoon had “more correlation with a ransomware group or other cybercriminals” than with Chinese state hackers. This was the first time that China used public cyber attribution as a tool of retaliation to counter other countries’ public cyber attribution against China.

In a surprising turnaround, Chinese officials later tacitly acknowledged responsibility for the Volt Typhoon intrusions into US infrastructure, the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) reported on April 10. In a secret December 2024 meeting, Chinese officials "indicated that the [Volt Typhoon] infrastructure hacks resulted from the U.S.'s military backing of Taiwan," the WSJ reported, citing a former US official and other sources “familiar with the matter.” In what the WSJ characterized as an apparent attempt "to scare the U.S. from involving itself if a conflict erupts in the Taiwan Strait," this reported signaling to the US government in December 2024 would represent a remarkable shift from the attempt in April 2024 to blame the Volt Typhoon activity on cybercriminals.

In addition, we noticed that Qi An Xin and its former parent company, Qihoo 360, are the two main Chinese cyber security companies that have worked with the Chinese government on public cyber attribution since 2019. For example, Qi An Xin’s 2023 Mid-Year Global APT Report named the likely Taiwan-based group GreenSpot (i.e. PoisonVine) as a top APT group targeting China. Antiy and DBAPPSecurity, which participated in the effort of calling out PoisonVine in March 2025, are new to the name-and-shame game.

China’s Attribution to the U.S. Has Advanced to a Direct “Wanted” Notice

China’s public cyber attribution targeting the United States explicitly began in 2019 with Qi An Xin publishing a Chinese-language report in September 2019 accusing the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of hacks against Chinese aviation targets between 2012 and 2017. Following that, Qihoo 360, in March 2020 and March 2022, published two reports about alleged hacking activities attributed to the CIA and to the US National Security Agency (NSA), respectively. Later, Qi An Xin’s Pangu lab published a February 2022 report discussing technical details of a backdoor that it said the allegedly NSA-linked hacking team Equation Group had used, and a follow-up technical report on the same backdoor in September 2022. These reports did not independently establish attribution. Rather, they either elaborated on or originated from leaked material, such as the 2017 Vault7 and Shadow Brokers leaks of purported CIA and NSA materials, respectively. They similarly did not name specific individuals responsible for the operations.

The release of the public statement by the Harbin Public Security Bureau on April 15 (image below), naming three alleged NSA agents for their involvement in cyberattacks against the February 2025 Asian Winter Games, marks a turning point in China’s attribution effort against the U.S.

Roughly two weeks earlier, on April 3, the CVERC and the National Engineering Laboratory for Computer Virus Prevention Technology (NELCVT) published a report titled “Cyber Threat Report of the 9th Asian Winter Games Harbin 2025.” That report attributed a cyber campaign during the Games to the U.S. government but did not name the NSA or any specific individuals. Its technical evidence was limited to a list of IP addresses allegedly linked to the attacks, without providing further context or corroboration.

The April 15 statement by the Harbin Public Security Bureau appears to build directly on that report, elevating its claims into the realm of law enforcement by naming individual NSA operators and offering monetary rewards for information leading to their capture. On the same day, major state media outlets Xinhua and Global Times published English-language articles just two minutes apart, reporting on the Harbin Bureau statement. While the Global Times article was largely a direct translation of the statement, Xinhua’s version included additional details not found in the Harbin Public Security Bureau release. About twenty minutes later, a second Global Times article echoed the added information.

According to the two outlets, citing investigations by Chinese technical teams—identified in the second Global Times article as CVERC and the NELCVT—the following findings were reported:

The NSA targeted core systems of the Asian Winter Games, including registration, travel, and competition entry platforms that stored sensitive personal data;

NSA attacks peaked on February 3, coinciding with the first ice hockey match, and aimed to disrupt critical information systems;

The NSA also allegedly targeted critical infrastructure in Heilongjiang Province, including sectors such as energy, transportation, water, telecommunications, and defense research;

During the Games, NSA operatives reportedly sent encrypted data packets to Windows devices in the region, likely attempting to trigger pre-installed backdoors;

Technical teams further implicated the University of California and Virginia Tech in the broader cyber campaign;

Despite the volume of claims, neither the articles nor the April 3 report provided technical evidence to substantiate them. With regard to the two universities, the second Global Times article only claimed that “The [technical] team traced and analyzed the IP addresses that took part in the cyberattacks during the Asian Winter Games in Harbin and found that IP addresses of 169.228.*.* and] 45.3.*.* [are] attributed to these two universities.” This level of evidence is generally considered insufficient, as IP addresses alone can be unreliable indicators. They can be spoofed, routed through proxies, or originate from compromised machines—especially in large, open academic networks like those at the University of California or Virginia Tech.

The lack of new technical detail in the police statement and its reliance on the earlier April 3 report—combined with the elevation of the case to a public arrest warrant—raises questions about the timing and intent behind the release. One possible explanation is the broader context of rising tensions between China and the United States, as the Trump administration imposes additional tariffs on Chinese goods. Another possibility is a more cyber-specific dynamic, potentially linked to the recent Wall Street Journal article mentioned above, in which Chinese officials reportedly acknowledged that China was behind the Volt Typhoon cyber campaign—an unusually candid admission in the ongoing contest over narrative control in cyberspace. In parallel, the cumulative pressure of sustained U.S. actions—including indictments of Chinese nationals and sanctions against firms allegedly involved in cyberespionage—has intensified over the past several months. The Harbin statement may therefore represent an effort to shift the focus and reframe China’s role from that of a perpetrator to a victim in cyberspace.

Overall, this attribution effort stands out as a shift in China’s approach to publicly accusing the United States. The naming of alleged NSA operators, the offering of monetary rewards, and the involvement of China’s Ministry of Public Security (MPS) all represent new elements in China’s attribution efforts. Notably, the use of the MPS—rather than the Ministry of State Security (MSS), which spearheaded the latest attribution efforts targeting Taiwan—may be linked to the potential issuance of arrest warrants. This approach appears to mirror the style of U.S. Department of Justice indictments, though with fewer details, no supporting documentation, and no photographs of the alleged perpetrators.

Naming and Shaming Alleged Taiwan-linked Hackers: MSS Focuses on Attacking “Taiwan Independence Forces”

Roughly one month before naming and shaming U.S. operatives, China directed similar accusations at Taiwanese hackers. In March 2025, the Ministry of State Security (MSS) published a post on its official WeChat account identifying alleged Taiwanese hackers. On the same day, the English-language website of the Chinese Ministry of National Defense reposted a report from the Global Times, an internationally distributed media outlet of the Chinese Community Party. Citing the MSS statement, the Global Times report said China’s national security agencies “have identified multiple individuals involved in the planning, commanding, and executing” of cyber infiltration activities against mainland China.

This marked the second such disclosure in recent months. The first came in September 2024, when the MSS accused the hacktivist group “Anonymous 64” of having ties to the Taiwanese government. That earlier report claimed hacktivist group “Anonymous 64” had links to the Taiwan government, and it named three alleged active-duty personnel who it said carried out hacking activity against mainland China, Hong Kong and Macau. Both the September 2024 and the March 2025 public announcements from the MSS named the identified hackers as the “Internet Army of Taiwan Independence”(“台独”网军) and warned Taiwan that “reliance on hacking for independence is ultimately a dead end.”

By framing the actors as part of the “Taiwan Independence Forces,” the MSS appeared to send a warning message to anyone promoting Taiwan independence. The use of the phrase “hacking for independence” could be an effort to associate Taiwan’s pro-independence government with hacking. It might refer to Taiwan’s continued resistance against China’s efforts at reunification. Alternatively, it might imply that Taiwan is seeking to break out of its current ambiguous international status and seek formal international recognition as an independent state. The Chinese government insists that Taiwan is part of China, that complete reunification is inevitable, and that it reserves the option to use force to achieve it – even though no specific timeline has been set.

There are notable differences in structure, level of detail, and overall messaging between the MSS posts from September 2024 and March 2025 about the alleged hackers. The more recent release adopts a sharper tone and suggests a shift in strategic objectives—emphasizing naming and shaming of alleged hackers and imposing reputational costs.

The September 2024 post is structured around Anonymous 64, portraying it as a state-linked hacktivist group. It introduces the group’s activities, institutional ties, and tactics over several sections, only revealing the names and photos of identified individuals at the very end. This structure emphasizes the group as a threat and frames its members as supporting actors. In contrast, the 2025 report leads with the alleged hackers, with information about the cyber unit they belong to provided later, almost as supporting context. Here, the focus is squarely on the individuals themselves.

The level of detail also differs. The 2024 post includes names, photos, and general roles, describing them as “active-duty personnel of the Taiwan Information and Communications Technology Army.” The focus remains on their affiliation and involvement in cyber activities. The 2025 post provides fuller profiles – covering different individuals – including birth dates, Taiwan ID numbers, and specific positions within Taiwan’s ICEFCOM. This increase in specificity reinforces the naming-and-shaming tactic at the individual level and might also imply that the MSS has mapped internal structures with some granularity. However, ICEFCOM countered that “China took pictures from the public domain to back up its assertion that the four Taiwanese service members were behind the alleged cyberattacks,” according to Focus Taiwan, the English arm of Taiwan's state-run Central News Agency (CNA).

Finally, the 2025 post includes a unique element: critique of the internal dynamics and working culture of ICEFCOM. It describes dysfunction within the “cyber army,” portraying senior officials as corrupt, exploitative, and self-serving, “greedy for achievements… appropriating the ‘merits’ of their subordinates… exaggerating, misrepresenting, and fabricating the ‘results’ of cyberattack activities to claim credit…pocketing funds under the guise of executing tasks, inflating expenses, colluding with external forces to ‘earn the difference’…” Ironically, the statement is thus inflating the maliciousness of the alleged Taiwanese cyber threat activity but also minimizing its effectiveness.

This posting – which was publicized both within China and in internationally focused media – appears aimed at different audiences.

First, by claiming access to internal dysfunction and highlighting cases of corruption, the post might seek to undermine the agency’s credibility both domestically and abroad, raising doubts about its integrity and effectiveness. The inclusion of details that would typically be classified suggests either deep infiltration or a deliberate psychological tactic.

Second, by depicting a toxic, hierarchical work culture, the report may be intended to deter skilled professionals from joining or remaining in Taiwan’s cyber units, framing them as professionally unrewarding and personally risky. This kind of internal critique is absent from the 2024 post, which maintains a clearer focus on Anonymous 64's offensive threat activities against China itself.

Three Cybersecurity Firms Join MSS in Naming and Shaming Taiwan

The MSS post was published simultaneously with reports from three major Chinese commercial cybersecurity firms—Qi An Xin, Antiy, and DBAPPSecurity—reflecting a coordinated and large-scale effort. The Chinese government likely directed the companies to release reports on the same actor PoisonVine (毒云藤) (a.k.a APT-C-01, Greenspot (绿斑); also written “Poison Vine”) but from different angles, each detailing different tools and case examples. Interestingly, both Antiy and Qi An Xin have reported PoisonVine activity before. However, both companies’ previous reports did not attribute the group to Taiwan explicitly. To the extent that their reports were coordinated with the Chinese government, this suggests the Chinese government is shifting in its tactics toward Taiwan’s government. It is explicitly accusing the Anonymous 64 hacktivist group, the Taiwanese government, and “‘Taiwan independence’ separatists” more broadly with carrying out hybrid warfare against mainland China. This signals a more confrontational posture than before.

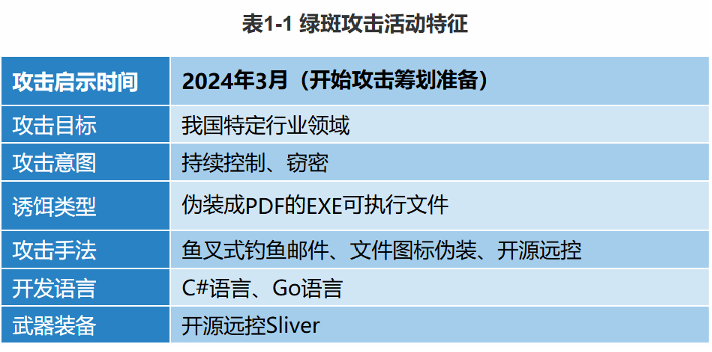

The Antiy report, building on its 2018 analysis of the group, provides a technical deep dive into APT-C-01 (PoisonVine) activity observed in the second half of 2024, with planning traced back to March. It details a spear-phishing campaign that lured victims to fake government websites, triggering the download of an executable EXE file disguised as a PDF document. Once executed, the file retrieved and decrypted a hidden payload—a remote access tool (RAT) based on Sliver, an open-source command-and-control framework. Designed as a legitimate alternative to Cobalt Strike for penetration testing and red teaming, Sliver is widely used by security professionals but has also been weaponized by threat actors. In this case, the tool connected to attacker-controlled servers, enabling persistent access and allowing the attackers to move laterally, gather intelligence, and exfiltrate data.

The DBAPPSecurity report adopts a distinctly strategic tone, opening with a broad framing of cybersecurity’s national importance and positioning Taiwan as a persistent cyber threat to mainland China. It stands out among the three reports as the only one to directly reference the four individuals publicly identified by the Ministry of State Security (MSS), outlining their affiliation with Taiwan’s ICEFCOM and some contextual background on the agency’s function and activities. The report characterizes ICEFCOM as “a malignant tumor endangering cyberspace security” and accuses it of hiring civilian hackers and cybersecurity firms to execute cyber warfare directives issued by the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) authorities—the party of Taiwan’s sitting president—including intelligence theft, sabotage, and counter-propaganda efforts.

DBAPP also highlights the group’s 2024 activities—drawing on different examples than those used by Antiy—identifying similar tradecraft, particularly the use of spear phishing campaigns that redirect victims to credential-harvesting websites as an initial access vector. However, in contrast to Antiy’s emphasis on the open-source C2 framework Sliver, DBAPPSecurity shifts the focus to the group’s deployment of closed-source remote access Trojans (RATs) such as Poison Ivy and ZxShell, long-used within Chinese-speaking APT groups for remote surveillance, credential theft, and persistent access.

Lastly, the Qi An Xin report is the most detailed of the three, following a structure similar to Antiy’s by documenting spear-phishing campaigns and phishing websites that redirected victims to fake government portals. These sites delivered EXE files disguised as PDFs, which, once executed, decrypted and deployed remote access tools such as Cobalt Strike or Sliver for remote and persistent access. In addition, Qi An Xin described APT-C-01’s phishing infrastructure, domain registration, and the use of known (N-day) vulnerabilities—particularly in routers, cameras, IoT devices, and firewalls—for initial access and lateral movement.

The Qi An Xin report also exposes some of PoisonVine group’s mistakes, including misconfigured phishing servers that inadvertently exposed stored credential logs and phishing site source code. It is the only report to explicitly assess the group’s capabilities, concluding that “their attack methods are not particularly sophisticated, and the network weapons they use are not particularly complex.”

Escalation of Wars in Cyberspace

China’s shift in attribution approach towards Taiwan and the U.S. within a 30-day period marks a major turning point in its public attribution of cyber threat activity. What started as general accusations against U.S. agencies has now advanced to naming alleged American hackers in an outright “wanted” notice, complete with a bounty. The explicit attribution to Taiwan—both as a state actor and through the outing of individual hackers—is just as significant, particularly given the long history of reporting on the allegedly Taiwan-linked group PoisonVine, none of which had previously named Taiwan.

Chinese cybersecurity firms now attributing operations to Taiwan have reported on PoisonVine as early as 2018 and claimed the group’s activities could be traced back to 2007. However, these early reports had no attribution. In September 2018, Qihoo 360’s Helios Team published the first PoisonVine report, describing the group’s “11 year’s cyber espionage activities” from 2007 to 2018. In 2020, Qi An Xin’s Red Raindrop team published another report about PoisonVine’s phishing campaign targeting Chinese entities during the Covid-19 pandemic, but again without attributing it to Taiwan. In July 2023, Qi An Xin’s Mid-year Global APT Report listed GreenSpot (i.e. PoisonVine) as the most active group targeting Chinese entities during the first half of 2023. The report only attributed the group to its geographic region but didn’t mention Taiwan. None of these reports attributed the group to the Taiwanese government. Instead, for example, the Qi An Xin Red Raindrop team’s report only described PoisonVine as “an APT group that has been targeting key units and departments of China’s military, government, science and technology, education, and maritime agencies.”

It appears that the Chinese government previously restricted cybersecurity companies from publicly attributing cyber operations to Taiwan and that only in March 2025 were cybersecurity companies allowed to point openly at Taiwan for alleged hacking activities. This change suggests that the Chinese government is ready to face direct conflicts with Taiwan in cyberspace. Taiwan is the second country, other than the U.S., to whom China has publicly attributed cyber operations. From China’s perspective, a “Taiwan compatriot” —in Chinese parlance, a Taiwanese citizen who should really be considered a citizen of greater China— is as bad as the U.S.

Interestingly enough, the Natto Team and other researchers have discovered that it wasn’t just Chinese cybersecurity companies reporting on PoisonVine (APT-C-01/GreenSpot) targeting China, but also a U.S.-based company. In February 2025, Hunt.io reported that PoisonVine had targeted visitors to the website 163.com using fake download pages and spoofed domains. 163.com belongs to NetEase, one of China’s largest IT companies, which provides online gaming, email services and other online services. Hunt.io’s findings of PoisonVine’s tactics reflect those in Qi An Xin’s Red Raindrop 2020 report, which also identified PoisonVine using similar phishing techniques targeting 163.com services with fake login pages. Taken together with China’s shift toward outing alleged U.S. hackers, this growing pattern of mutual exposure and cyber posturing makes us realize that China’s war in cyberspace with the U.S. and Taiwan, despite being without smoke, is escalating.

Natto Thoughts is a reader-supported publication. Your paid subscription supports access for all and serves as a token of appreciation for the efforts of the Natto Team

Information, Communications and Electronic Force Command (ICEFCOM) is one of the two “Military Establishments” (the other one is Military Police Command) under Taiwan’s Ministry of National Security, according to the website of Ministry of National Defense Republic of China updated on January 1, 2022.

The Natto Team has seen reports using “PoisonIvy” for the name of this APT group. This is likely a translation variation from the group’s Chinese name “毒云藤”. We choose to use “PoisonVine” to match the naming convention of Chinese information security companies.

Introduction to Malware Binary Triage (IMBT) Course

Looking to level up your skills? Get 10% off using coupon code: MWNEWS10 for any flavor.

Enroll Now and Save 10%: Coupon Code MWNEWS10

Note: Affiliate link – your enrollment helps support this platform at no extra cost to you.

Article Link: https://nattothoughts.substack.com/p/wars-without-gun-smoke-china-plays