Click here to download the complete analysis as a PDF.

For several years, Recorded Future has been developing tools and methodologies for detecting and analyzing influence operations by nation-states and others. We have recently upgraded some of these tools and applied them to detecting a new kind of influence operation, which recycles old news about terror incidents by publishing them to appear as new. We refer to this technique as “Fishwrap.” This operation is also using a special family of URL shorteners that allow attackers to track click-through from social media posts used in their campaigns.

Key Findings

- We have developed new algorithms for identifying influence operations. These algorithms allow for the detection of “seed accounts,” which can be used to analyze additional accounts engaged in an operation.

- Behavioral analytics based on topological methodologies can be used to analyze the highest-likelihood participants in an operation and cluster those with the highest degree of similarity.

- Using this methodology, we identified a new kind of influence operation: Fishwrap. This methodology uses old terror news masquerading as new.

- Over 215 social media accounts participating in the Fishwrap operation were analyzed.

- These social media accounts use a special family of at least 10 different URL shortener services that allow for tracking the effectiveness of the operation. All of these URL services are running the same code and are hosted on the same commercial infrastructure.

- The accounts’ behavioral similarity leads us to believe that they are all part of the same influence operation.

- Since account holders are most likely fictive and the domains used for the URL shortener services are registered anonymously, attribution is difficult — however, research is ongoing.

Influence Operations

RAND Corporation defines information operations and warfare, also known as influence operations, as the collection of tactical information about an adversary, as well as the dissemination of propaganda in pursuit of a competitive advantage over an opponent.

Recorded Future and its partners have been engaged in identifying and characterizing influence operations for more than five years, with studies including how terror supporters spread propaganda, election hacking in the U.S. in 2016 and 2018, and how China uses social media to influence U.S. opinion.

Influence operations are, of course, not an exclusive nation-state activity — political groups use the same mechanisms, as do criminals engaging in stock manipulation activities.

The Anatomy of an Influence Operation

Influence operations that aim to change public opinion (for example, trying to sway the outcome of an election) need to reach a large number of people with messages that resonate with their beliefs or fears. Previously, certain groups, including the Nazis in the 1930s all the way to the Hutus in the 1990s, used radio to obtain massive reach. Today, social media has become the channel of choice for influence operations. Using data-driven profiling, messages can be personalized, as highlighted by the Cambridge Analytica scandal.

Even though “fake news” has become highly associated with influence operations, in many cases, “real news” is also used, but it’s carefully selected to emphasize the opinions the operation wishes to foment. These news pieces can be distributed in different ways, such as through paid advertising (as in the Cambridge Analytica case), by using a large number of social media accounts that are controlled by humans (so-called “trolls”), or with algorithms. Advertising campaigns are hard to detect without access to users’ news feeds, but campaigns using ordinary social media posts by a large number of accounts will be possible to detect by using a solution such as Recorded Future.

Detecting and Tracking Influence Operations

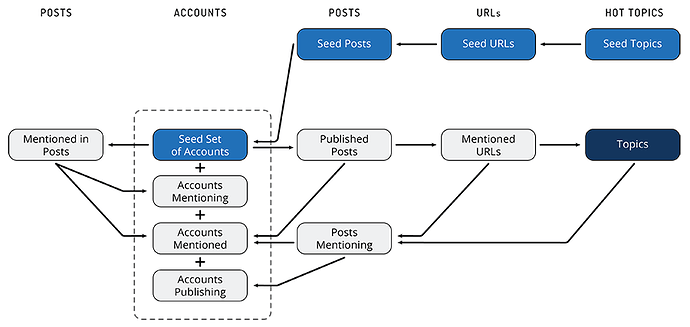

To detect an influence operation, we need a starting point — a seed. This can be a particular story that is used by the operation engaging in it. Once one or more seeds have been selected, we can broaden the scope of our investigation by finding related topics, such as URLs, hashtags, and user accounts. The image below illustrates how our Snowball algorithm can be used to grow the number of potential accounts engaged in an operation, starting with either a few accounts or with some topics believed to be used by an operation.

The Snowball algorithm generates a large number of candidate accounts, but will also typically find many false positives since “innocent” accounts will repost news from the operation. To decide which accounts are really part of the operation, we can use behavioral analytics to characterize and cluster the activities implicated by the Snowball algorithm.

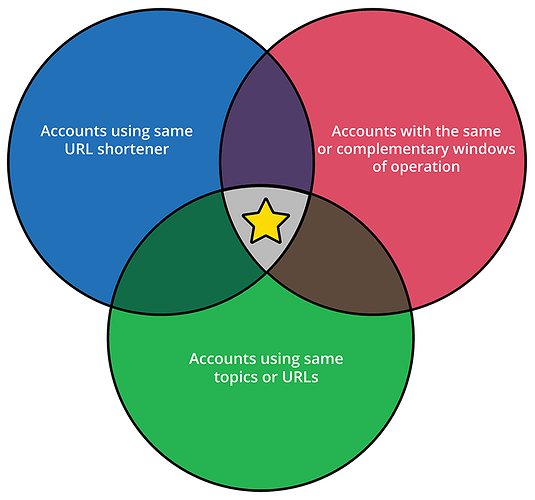

Our approach to analytics is to define a number of similarity metrics over a large set of social media accounts. For example, accounts are more similar if they:

- Post the same URLs and hashtags — the similarity is stronger if only a few accounts post a certain URL or hashtag within a certain time frame

- Post on the same topics, as defined by the entities and events they mention

- Are using the same URL shorteners

- Have similar temporal behavior — either their overall period of activity or their weekly or daily behavioral patterns

- Have mutually exclusive but adjacent overall periods of activity — this is a weak but not insignificant indication that one account has replaced the other

- Have similar account names, as defined by the editing distance between their names

All of these different similarity metrics can be used to cluster accounts. We then look at sets of accounts which are associated with multiple identical similarity clusters. These accounts are highly likely to be part of the same influence operation. Accounts which are related only through joint membership in one cluster are not very likely to be part of the operation — they are just associated (for example, by having reposted a post originated by the operation).

Fake News in Influence Operations: 2 Examples

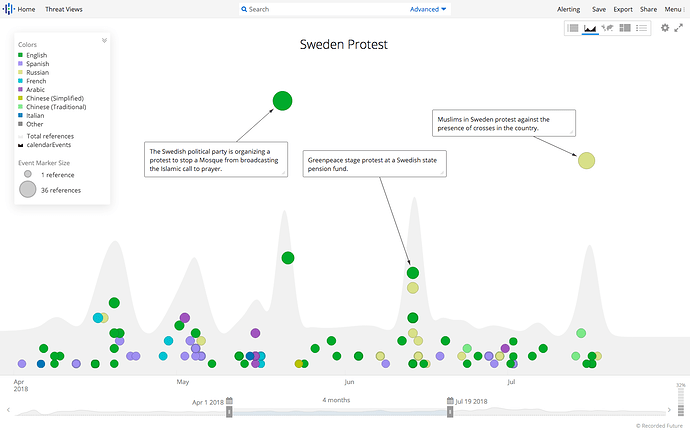

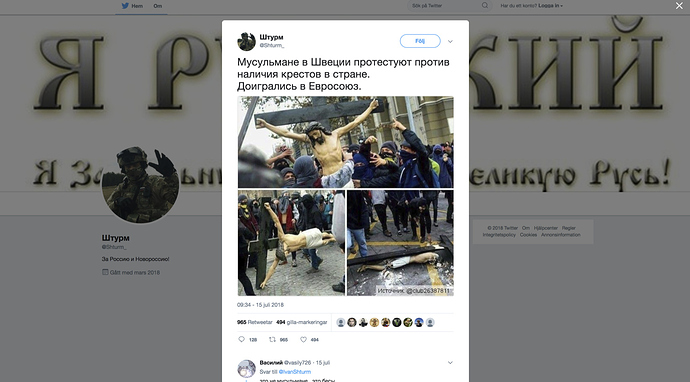

Identifying fake or biased news can be hard, but by looking at some examples, we can gain some insight. For example, in a timeline view of reports on protests in Sweden in 2018, one event on July 16, 2018 regarding Muslims protesting against crosses stands out because it is only being reported in Russian. This is quite strange for what should be major news in Sweden, and different from all other major protests during the period.

Even though we first found this “news” in Russian, it was also referenced by other social media accounts (like U.S. alt-right ones).

This particular story turns out to be entirely fake, and in this case, we could actually use a reverse image search to find the original story, which turns out to be about students protesting in Chile two years earlier.

This example validates our intuition that important news stories which are reported either only in a single language, in a surprisingly small volume, or only on social media, are good initial candidates for being fake or hyperpartisan news used in an influence operation.

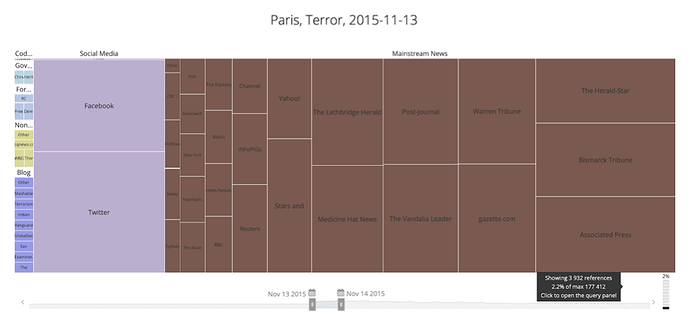

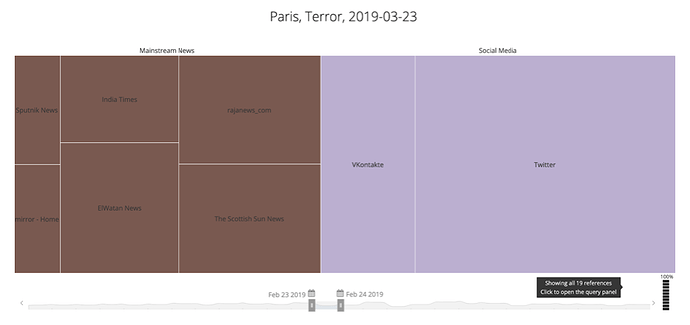

As another example, we compared the actual source distribution of a real terror event that took place on November 13, 2015 in Paris (177 thousand references, mostly in mainstream media) with fake news about an event in Paris on March 23, 2019 (only 19 references, mostly on social media). The account similarity associated with being one of the few accounts posting on March 23, 2019 is much higher than that associated with being one of thousands of accounts posting on November 13, 2015.

Fishwrap: A New Influence Operation

The fake Paris terror event mentioned above is actually part of an influence operation that we have detected using our new algorithms. This operation is focused on posting old terror news stories as if they were new, probably with the goal of spreading general fear and uncertainty. We call this operation Fishwrap, since it uses old news for other purposes.

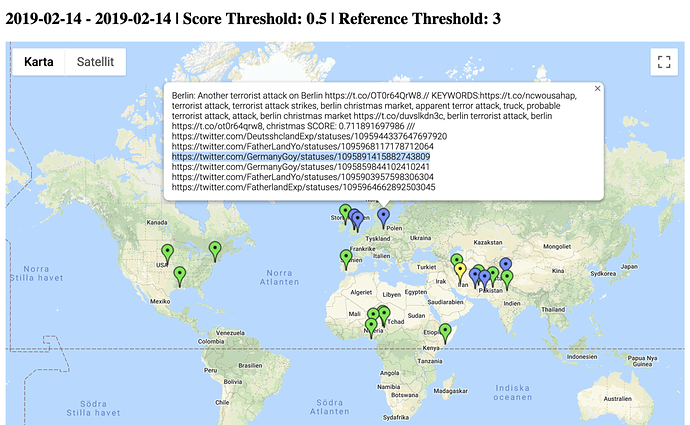

We first detected Fishwrap through our automatic tracking of terror events only reported by social media, like the Paris example above. Below is another example of such event reporting.

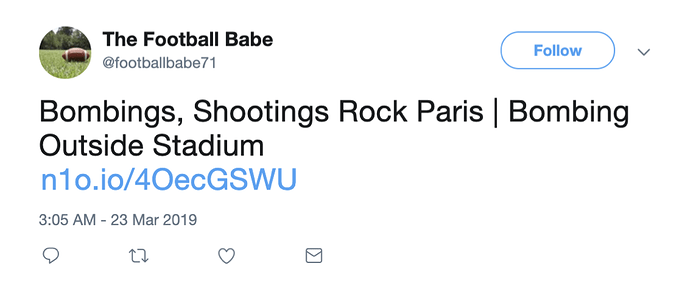

By tracking terror events in Recorded Future that were only reported on social media, we were able to find a set of about a dozen accounts clearly engaged in spreading old terror news as if it were new. The reason we compared the specific dates in the Paris terror example above is because of a social media post from March 23, 2019 reporting on an event shown in the image below.

However, the URL-shortened link in the post led us to an article about the original event from November 13, 2015. While many readers would probably not scrutinize the publication dates, it is easy to see how the post could cause concern for those reading it and prompt them to follow the link to validate the news, missing the difference in publication date.

By applying the Snowball algorithm to the small set of identified posts, we could swiftly grow the number of suspicious activities in this operation to more than a thousand profiles.

Narrowing It Down

We then looked at the similarities within this fairly large set of accounts and concentrated on three specific aspects:

- Temporal behavior

- The domain of the URLs referred to in the accounts’ posts

- Account status

Temporal Behavior

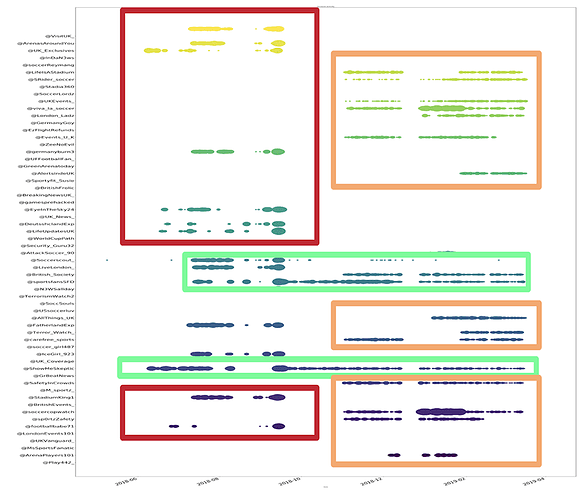

By plotting the activity (postings) of all accounts found in the operation, we can identify different activity periods.

We clearly see three different clusters of accounts:

- Those active between May 2018 to October 2018

- Those active between November 2018 to April 2019

- Those active during the entire time period, between May 2018 to April 2019

These temporal patterns indicate the launch of a number of accounts in May 2018, many of which were shut down in October 2018. These were followed a few weeks later by a new batch of accounts with the same behavior and still in operation.

Topic Similarity: URLs and Domains Used

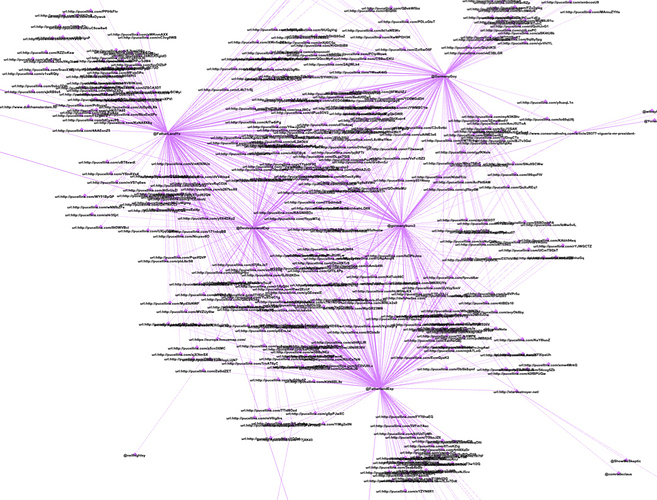

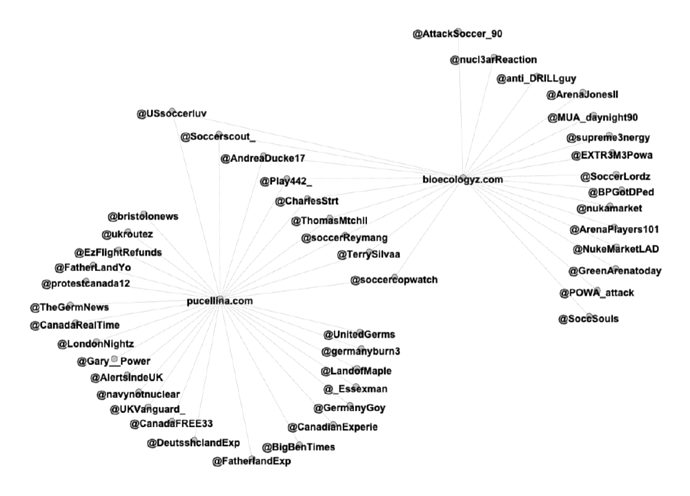

By looking at the URLs posted by a subset of the accounts, it is clear that there is some relationship between them since they, to some extent, post identical URLs.

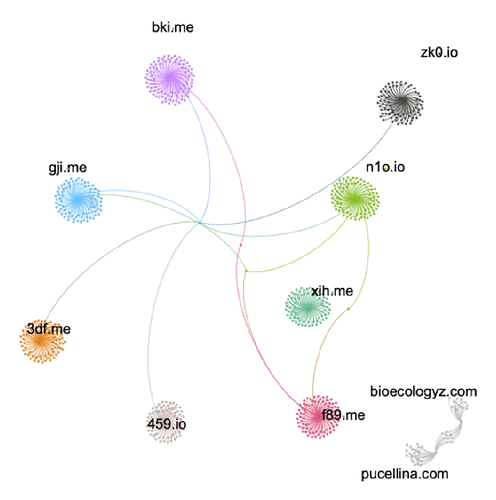

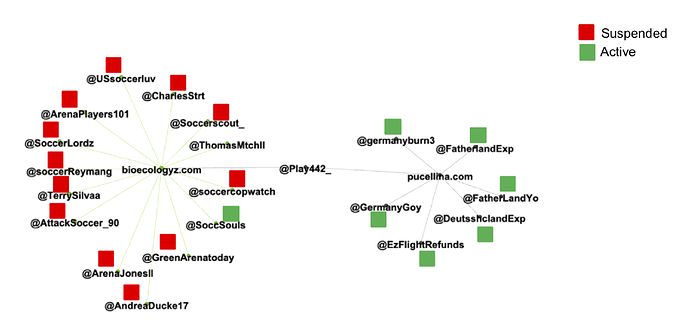

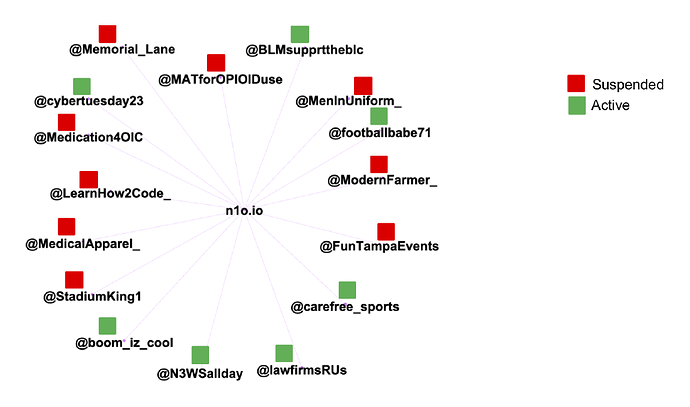

The graph above looks quite complicated. However, if we focus only on the domains of these URLs, a much simpler picture emerges, shown below.

It turns out that a lot of the accounts are posting all of their links through a small number of URL shortener services (in the example above, pucellina[.]com and bioecologyz[.]com). More precisely, we can identify 10 domains hosting URL shortener services that are used for essentially every single post made by 215 of the identified accounts. As seen in the graph above, some accounts use multiple URL shorteners, and thus show that there is an indirect connection between accounts using different shorteners. Overall, we can see that each domain has a fairly large number of accounts that has published some reference to it, and a very small number of accounts have published a reference to more than one of the domains (based on the data we’ve collected). The exception is the two domains pucellina[.]com and bioecologyz[.]com, where a larger number of accounts have published references to both domains.

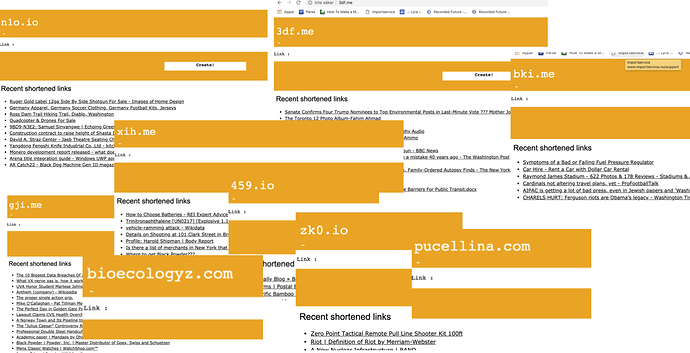

It gets more interesting! Upon inspecting the 10 different URL shortener websites, we immediately see that their appearance is identical.

This is strong evidence linking all 215 accounts to 10 URL shorteners, which in turn appear to be running the same code. Interestingly, an inspection of the HTML code for the URL shorteners also reveals that these domains seem to be tracking all agents that follow the links. This could be to measure the effectiveness of the operation, but it might also be used for profiling the “captured audience” of the operation.

Unfortunately, all of these 10 domains are anonymously registered, and we cannot see who registered or owns them. We did investigate where these services are hosted, and it turns out they are all currently running on dedicated servers on Microsoft Azure.

| Domain | Created | Updated | IP | Selected Historic Name Server | Mentions |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 459.io | 2018-04-26 | 2018-06-25 | 40.117.116.52 | 24,156 | |

| n1o.io | 2018-04-27 | 2018-06-26 | 23.98.135.84 | 14,113 | |

| 3df.me | 2018-04-27 | 2018-06-26 | 104.209.158.224 | 20,315 | |

| bki.me | 2018-04-27 | 2018-06-26 | 23.96.7.223 | adminsky.cn | 17,703 |

| gji.me | 2018-04-27 | 2018-06-26 | 104.209.183.79 | xincache.com | 15,801 |

| xih.me | 2018-04-27 | 2018-06-26 | 13.78.148.193 | 22.cn | 9,353 |

| zk0.io | 2018-04-27 | 2018-06-26 | 23.101.187.48 | 16,549 | |

| pucellina.com | 2018-09-17 | 2018-09-17 | 104.209.246.70 | 5,983 | |

| bioecologyz.com | 2018-09-17 | 2018-09-17 | 40.76.26.54 | 3,215 | |

| f89.me | 2018-04-26 | 2018-06-25 | 13.78.137.38 | 22.cn | 11,232 |

We can clearly see two clusters of domains corresponding to the two time frames we identified in the temporal analysis above. The first eight domains were created just prior to the observed start of the campaign (the red accounts in the temporal analysis above), and the last two domains were created some weeks before the launch of the second wave of the campaign (the orange accounts in the temporal analysis above).

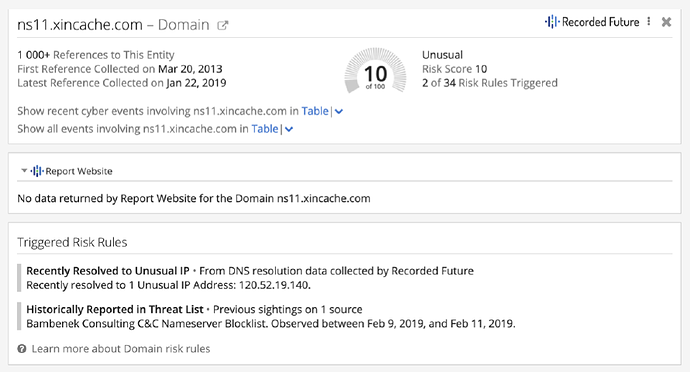

We can also see historic name servers for a couple of domains, but this does not give us much additional information. None of the 10 domains have any risk score in Recorded Future — the only trace of malicious activity is that one of the previous name servers has been associated with a suspicious IP number and a malware command and control server.

Sadly, due to anonymous registration, this is where our trail ends! We can only speculate as to who registered these domains and is running the network of social media accounts that use them. The fact that the operation has been going on for close to a year, and that it is spending money on numerous domains on dedicated servers, leads us to believe this is not just someone running the operation “for the lulz,” but rather, a political organization or nation-state with an intent to spread fear and uncertainty and track followers of the posted links.

Account Status

Upon closer inspection of the status of the accounts, we note that a fair percentage of them have been suspended. The degree of suspension varies between different URL shortener service clusters, but it is clear that there has been no general suspension of accounts related to these URL shorteners. We believe one reason for this is that by posting links related to old, but real, terror events, the accounts are not in clear violation of any terms of service, and therefore have not been suspended due to either automatic identification or manual reporting.

Conclusion

Based on a long track record of investigating influence operations, we developed a set of algorithms for identifying and analyzing such operations. Using these algorithms, we have identified a fairly large influence operation that uses old terror events repackaged as breaking news to gain attention. Using behavioral analytics, we have shown how more than 215 accounts have participated in or are participating in this operation. The operation uses a set of dedicated URL shortener services to link to old news, and this mechanism allows the operation to track the efficiency of its operation and possibly to analyze what kind of audience (at least geographically) it succeeds in targeting.

The post The Discovery of Fishwrap: A New Social Media Information Operation Methodology appeared first on Recorded Future.

Article Link: https://www.recordedfuture.com/fishwrap-influence-operation/