Editor’s Note: The following blog post is a summary of a presentation from RFUN 2018 featuring David Peduto (threat intelligence analyst), Christopher Kash (intelligence services consultant), and Julie Starnes (federal account executive) of Recorded Future.

Geopolitics can often seem far removed from the here and now. For many, official proclamations and state-sanctioned programs around the world may appear as amorphous as they are grandiose. Yet, understanding the localized impact of global realities is critical for organizations to ensure business continuity and the well-being of personnel. Recorded Future can help foster this understanding, thereby making geopolitics relevant for organizations operating around the world.

During a talk at this year’s Recorded Future User Network (RFUN) conference, moderated by Julie Starnes and led by Christopher Kash and David Peduto, Kash and Peduto provided a real-world example of using Recorded Future to make geopolitics relevant for organizations. The discussion centered on analyzing the implications of a geopolitical reality in the context of a single location — namely, how the Chinese government’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI, also known as “One Belt, One Road”) has impacted Djibouti. It provided for a localized, granular analysis of a hemispheric initiative that has global implications.

Belt and Road Initiative

First, an understanding of BRI is necessary in order to understand its impact. According to a “Visions and Actions” document put forth by the Chinese government in March 2015, BRI is meant to “instil vigor and vitality into the ancient Silk Road.” As such, BRI is promoted as an effort to engender cooperation, peace, and development along commercial corridors between the East and West. Of course, commerce requires an ability to bring goods to market, which in turn requires sound infrastructure. It is this latter point — infrastructure — that is a central element of the Belt and Road Initiative.

To that effect, BRI is projected to entail over $500 billion in investment across dozens of countries in Asia, Africa, and Europe. In an effort to assuage concerns that BRI may not be as benign an initiative as promoted, Chinese Premier Xi Jinping argued that BRI is not a “Chinese plot” in a speech in April 2018.

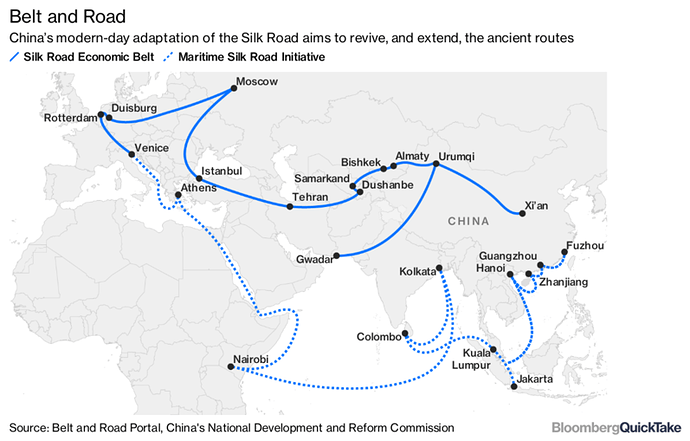

As for its component parts, BRI consists of two main elements — the Silk Road Economic Belt (SREB) and the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (MSR). The former is the land-based element of BRI, while the latter is its sea-based portion.

Map of the Belt and Road Initiative.

Displayed on a map, the resultant view of BRI is one that Halford Mackinder and Alfred Thayer Mahan, two grandfathers of modern geopolitical strategy, would be proud of. Mackinder promoted the so-called “heartland theory,” which argued that control of Central Asia (the “heartland”) was essential to asserting global power. Mahan, on the other hand, believed in the supremacy of sea power, using naval prowess as a necessary means to promote economic progress. These differing theories — one land-based, the other sea-based — come together in a visual display of BRI. Important to note is the fact that BRI also passes through several of the world’s oil chokepoints — the Strait of Malacca, the Suez Canal, and the Bab al-Mandeb strait.

So What?

On the western edge of the narrow Bab al-Mandeb strait, Djibouti sits like an anchor. Smaller than the state of New Jersey (with a tenth of its population), a desert landscape, and a 40 percent unemployment rate, Djibouti may not seem to factor large in global affairs. Yet, it factors into a consideration of BRI, especially so if it is a country in which your organization is doing business. Linking the Red Sea to the Gulf of Aden (and, by extension, the Indian Ocean), the Bab al-Mandeb is a critical link in the BRI’s Maritime Silk Road, thereby underscoring the importance of Djibouti’s geostrategic position. In addition, as The Economist notes, “In the past two years, Beijing has lent Djibouti some $1.4 billion” — this in a country with a GDP just over $2 billion. Of equally important note is the fact that, at the end of 2016, 82 percent of Djibouti’s external debt was owned by China.

All of this sets the stage for an in-depth look at understanding the implications of BRI in the context of a single location of interest through the use of Recorded Future queries.

Queries

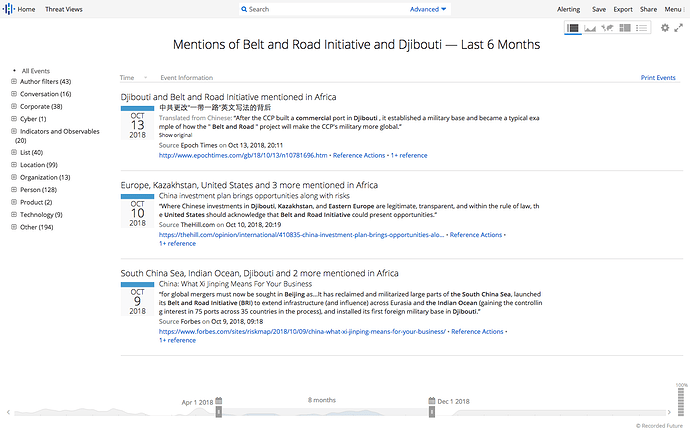

Recorded Future provides an effective way to gain a general understanding of the discussion involving BRI and Djibouti in a matter of seconds. By employing the Boolean logic inherent in the query builder, we can look at mentions across all types of sources involving both BRI and Djibouti over a given time frame. By expanding the table on the left-hand side of the page, we can see the key elements of the narrative that involve BRI and Djibouti. A cursory scan through the results reveals discussion of the Port of Djibouti. Noting this particular port, we can then focus a subsequent query on all Djiboutian ports that might be mentioned in the context of BRI.

Table of data mentioning both the Belt and Road Initiative and Djibouti.

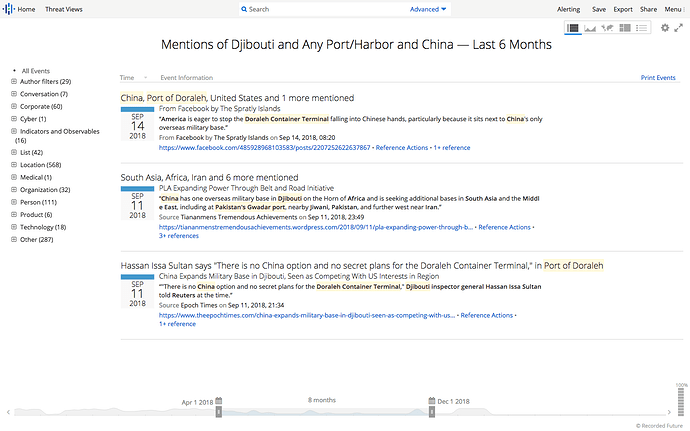

This is exactly what was done in the query below, which was changed slightly to provide the above-mentioned focus. In doing so, discussion of Doraleh Container Terminal (DCT) bubbles up, serving as an additional node for analysis. Further review of the content highlights the fact that China Merchants Port Holdings Co., a Chinese state-owned enterprise (SOE), has a stake in the DCT port. Importantly, the analysis also surfaced the fact that the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) has established its first overseas base in close proximity to the port. The PLAN base is also located six miles west of Camp Lemonnier, a U.S. military base.

Table of data mentioning Djibouti and China, as well as any port, harbor, or facility.

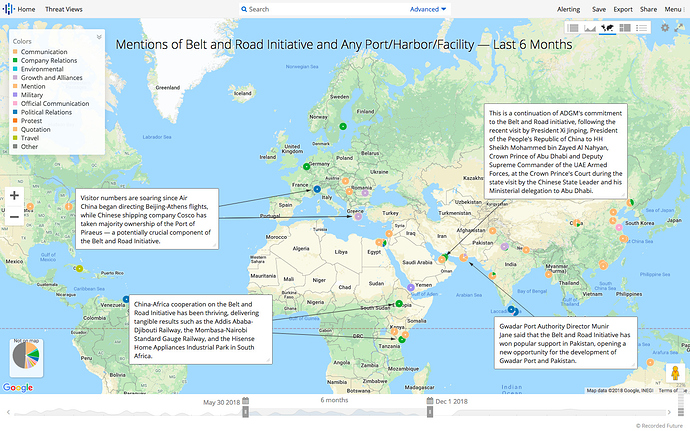

Having zoomed in, we can now zoom back out to get a sense of the larger discussion around BRI and ports on a global level. Doing so can help us look for events involving ports and BRI elsewhere that could serve as a precedent for what may transpire with the Doraleh Container Terminal in Djibouti. For example, the fact that the Sri Lankan government forfeited control of its Hambantota Port to the Chinese government in December 2017 for failure to pay its debts is unsettling for some concerned about the fate of Djibouti’s Doraleh Container Terminal.

Map of data mentioning both the Belt and Road Initiative and any port, harbor, or facility.

Conclusion

The presentation (and this blog post) sought to demonstrate how a seemingly abstract geopolitical reality can have very real consequences for an organization operating in a particular location. Djibouti could just have as easily been switched with another country, such as Pakistan, to highlight the impact of BRI on another location.

While BRI served as a focal point for analysis for this particular conversation, you have the ability to search for any endeavor — national or otherwise — in an effort to understand its impact on the ground in a given location. Whether it’s One Belt, One Road, the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), or any number of other international undertakings, you can make geopolitical realities relevant for your organization with Recorded Future, one query at a time.

The post Making Geopolitics Relevant: One Belt, Road, and Query at a Time appeared first on Recorded Future.

Article Link: https://www.recordedfuture.com/making-geopolitics-relevant/