After the public learned of the leaked documents from the Chinese Information security company i-SOON in February 2024, various media and analysts from the cyber security industry, including the Natto Team, seized the rare opportunity to uncover "the world of China’s hackers for hire". A year later, on March 5, 2025, the US Department of Justice (US DoJ) unsealed an indictment charging eight i-SOON employees and two officers of the Chinese Ministry of Public Security for alleged hacking activities from 2016 to 2023. The i-SOON indictment revealed further details on the company’s operation, particularly, how i-SOON actors coordinated with the Chinese Ministry of Public Security (MPS) and Ministry of State Security (MSS).

Indictments can be valuable resources for cyber threat intelligence (CTI) analysts: they provide insights into the activities, tactics, and infrastructure of threat actors, which can be used to improve threat detection and response capabilities. Indictments also identify threat actors, allowing CTI analysts to build a profile of known threat actors and understand the motivations and intents of those behind the keyboard. Since law enforcement agencies have visibility, sources, and methods for their investigations which may not always be available to researchers using open-source information, indictments give us an opportunity to expand our knowledge on those threat actors. On the other hand, US federal prosecutions draft charges with the knowledge that the allegations must be supported by evidence that can stand up under cross-examination in front of a jury and that guilty verdicts can be further challenged on appeal. Indictments thus might not address information that non-governmental sources such as threat intelligence researchers share more freely.

Although the Natto Team have done a great deal of research into the leaked documents from i-SOON in the past year (see here, here, here and here), the recently unsealed official documents related to i-SOON – including the indictment, a Most Wanted poster for the indicted i-SOON employees, and a warrant for seizure of Internet domains controlled by sometime i-SOON associate Zhou Shuai – provide new information and can yield insights that we might have missed before. Therefore, in this post, we would like to use i-SOON as a case study to evaluate how to leverage sources such as leaks and indictments. The Natto Team believes this approach is very helpful to sharpen up CTI analysts’ analytic process and learn how to evaluate and maximize the value of research sources.

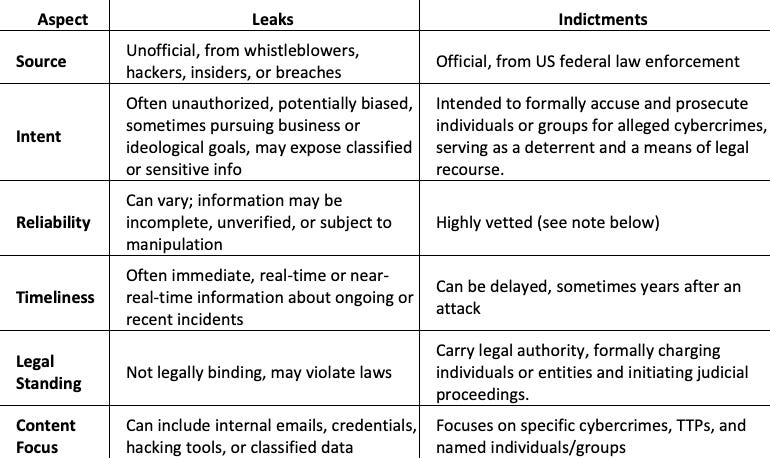

Leaks and Indictments: Similarities and Differences

Both leaks and indictments are valuable resources for cyber threat intelligence. However, they differ in their source, intent, and reliability. Understanding their similarities and differences is essential for CTI analysts to use them effectively. Given that many of the most widely publicized cyber-related indictments to date have come from US federal courts, the following comparison refers predominantly to US federal indictments from recent years. (Note: Legal systems in authoritarian countries such as China and Russia have traditionally operated very differently. Russia’s legal system, for example, is characterized not by rule of law but by “telephone justice,” where judges often make decisions based on telephone calls from powerful people. Law enforcement actions often serve to silence critics of the government or are part of power struggles among competing “clans” of officials and politically powerful individuals, even among security services themselves. In China, too, the ability to contest charges is limited. Indictments from China – such as the promised legal actions of alleged Taiwanese hackers – also merit their own special scrutiny).

Similarities

Both types of documents fulfill several similar functions:

Provide intelligence on threat actors and insight into their tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs): both leaks and indictments present details about threat actors and their methods.

Identify Indicators of Compromise (IOCs): Both sources may contain technical details such as IP addresses, domain names, and malware hashes, which are crucial for detecting and mitigating cyber threats. This aligns with the concept of tactical threat intelligence, which focuses on current threats and provides data on emerging campaigns and prevalent malware variants.

Help in attribution: both can assist in attributing cyber activities to specific individuals, groups, or nation-states, aiding in understanding the threat landscape and informing defensive strategies.

Can be used for threat mitigation: security teams can use data from leaks and indictments to update defenses, improve threat-hunting strategies, and strengthen cyber resilience.

Differences

At the same time, they differ in their sources, intent, reliability, timeliness, legal standing and focus.

In short, leaks provide raw, real-time, and sometimes unverifiable intelligence that, at their best, can expose or provide leads as to the real identity of threat actors, vulnerabilities, hacking tools, or attacker communications. At their worst, manipulated or selective leaks can mislead or waste valuable investigation time. Indictments provide formal, structured intelligence that is legally vetted but often comes with a delay.

In i-SOON’s Case…

In i-SOON’s case, two employees of i-SOON confirmed the leak with the Associated Press reporters a couple of days after the leak, and a few experts had medium to high confidence on the authenticity of the leaks. However, we have no information on who the leaker(s) is, what the intents are, and how reliable the leaked documents are, such as whether the leaked documents were complete or incomplete and have been manipulated or not. Security researcher BushidoToken conducted an analysis to judge who was possibly responsible for the i-SOON leak by using the Analysis of Competing Hypotheses (ACH) method. The results of his analysis mentioned that the leaker could be “a revengeful ex-employee,” a hypothesis supported by several “telling pieces of evidence.” In addition, a foreign intelligence agency could hypothetically be the leaker, or an anti-Chinese Communist Party (CCP) hacktivist group could be involved.

As to the indictment, Natto Team found that some information is similar to what we found in the leak, such as i-SOON’s clientele from MSS and MPS. Nonetheless, the indictment gives more details on US-based victims, TTPs and connections with MSS and MPS and the involvement of two MPS officers.

As a case study of leaks and indictments, Natto Team would like to provide a close look at i-SOON’s coordination with the Chinese government agencies and victims revealed in the indictment, comparing this to what we have learned previously from the leaked documents and open-source information.

i-SOON’s Coordination with MPS and MSS

i-SOON coordinated with bureaus and offices of the Chinese MPS and MSS, first courting them as customers, then working for them on hacking activities and training MPS and MSS employees.

i-SOON’s Government Customers

i-SOON’s primary customers were bureaus and offices of all levels of MSS and MPS. The Natto Team identified this information from the official indictment, open-source information, and the leaked documents.

From the i-SOON indictment:

The i-SOON indictment states, “i-Soon’s primary customers were PRC government agencies, including the MSS and the MPS. i-Soon worked with at least 43 different MSS or MPS bureaus in at least 31 separate provinces and municipalities in China.”

From open-source information:

In October 2023, when the Natto Team first identified i-SOON’s connections with Chengdu 404, the company allegedly behind Chinese state-sponsored threat group APT41, we discovered that i-SOON listed its business partners including all levels of public security agencies, including the Ministry of Public Security, 10 provincial public security departments, and more than 40 city-level public security bureaus. i-SOON also possesses relevant qualifications to work for state security. i-SOON is a designated supplier for the Ministry of State Security. In 2019, i-SOON appeared among the first batch of certified suppliers (列装单位) for the Cyber Security and Defense Bureau of the Ministry of Public Security (公安部网络安全保卫局) to provide technologies, tools or equipment. Subsequently, in 2020, i-SOON received a “Class II secrecy qualification for weapons and equipment research and production company (武器装备科研生产单位二级保密资格)” from the Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT). The Class II, the highest secrecy classification that a non-state-owned company can receive, qualifies i-SOON to conduct classified research and development related to state security.

From the leaked documents:

The leak clearly verified i-SOON’s line of public security clientele, as the Natto Team discovered four months before the leak, but also revealed that i-SOON served the Chinese People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and other government agencies. In the leaked Sichuan i-SOON contract list, 66 of the 120 contracts served various public security bureaus; 22 contracts served state security agencies’ needs; only one contract served the PLA – and that was also the only contract classified as “secret” – and the remaining 31 contracts served other government agencies, research institutes, state-owned enterprises, and universities.

i-SOON’s Hacking Activities

i-SOON’s work – “conducting hacking to steal data on behalf of the PRC government” is “at the direction of, and in close coordination with Chinese MPS and MSS,” as the indictment indicates. The leaked documents have suggested this coordination as well.

From the i-SOON indictment:

The i-SOON indictment alleges that i-SOON worked for the MSS or MPS on hacking activities in two types of situations – either at the direct request of the MSS or MPS, or in self-initiated hacking activities – then “sold, or attempted to sell, the stolen data to different bureaus of the MSS or MPS.”

From the leaked documents:

The Natto Team’s analysis of the leaked documents suggested that i-SOON had been proactively making educated guesses about the government’s next targets and following these hunches when undertaking those self-initiated hacking activities. Often, i-SOON has to figure out themselves what is valuable for their government clients. In January 2022, one person – likely an i-SOON employee – complained to another person, saying, “Now the clients are harder and harder to please. Unless the data we found matches what they need exactly, it is more and more difficult to cooperate with them.” In another chat log an employee tried to figure out what might interest the clients. “One idea is to have an inquiry system searching for those Uyghur ethnic people from Xinjiang who are in exile. If (we) need to do this, (we) need to have data from Turkey first. It is very difficult to do that. Whoever can do it, the other side [i.e. the government client] will definitely pay for it.” (Not for lack of trying: the i-Soon leak data appears to include credentials for the email service of Turkey’s Tubitak scientific council. However, that may not have yielded data relevant to Uyghur exiles).

i-SOON’s Training Services

The i-SOON indictment states that i-SOON provided trainings to MPS employees on how to hack. The leaked documents indicated that i-SOON offered its Capture the Flag (CTF) training program to the Public Security bureaus. The Natto Team has found that i-SOON followed closely on government policy directions to adjust their business operations. When the Ministry of Public Security issued guidance on the importance of “network defense and offense exercises” (网络攻防演习) and required all levels of Public Security Bureaus to conduct the exercise regularly, i-SOON executives saw this as an opportunity to promote the company’s Capture the Flag (CTF) training program to the Public Security bureaus. i-SOON CEO Wu Haibo, a.k.a Shutdown (sometimes written as “Shutd0wn”) said to general manager Chen Cheng a.k.a lengmo, “We are pretty good at doing trainings. Our CTF trainings are well recognized.” “Yes, many municipality bureaus have been asking us to help,” lengmo replied.

i-SOON’s Selling its Products

The i-SOON indictment alleges that i-SOON “cultivated relationships” with various bureaus of MPS and MSS and “sold its products to multiple bureaus.” The leaked documents from i-SOON vividly exposed how i-SOON executives and employees courted the government’s favor to obtain contracts through dinner parties or meeting in night clubs.

i-SOON’s Relationship with MPS Officer Wang Liyu

Lastly, the i-SOON indictment described how Wang Liyu, an MPS officer in Chengdu, allegedly worked with i-SOON on hacking activities. Wang “tasked i-Soon with hacking specific targets, including a U.S. news organization perceived as critical of the PRC government, and purchased data that i-Soon had stolen from victims’ computer systems.” Wang also “provided i-SOON with the username and password of the administrator account for a New York-based newspaper.” In the leaked documents, i-SOON executives Shutdown and lengmo mentioned in a chat conversation that Wang was promoted to the rank of section chief and invited Shutdown and others for a dinner and drinking party. This showed the close relationship between the MPS officer Wang and i-SOON.

More i-SOON US Victims Revealed

The i-SOON leaked documents show organizations in 38 countries, including the US, that i-SOON had the intent to hack or had compromised, according to research on the leaked documents by the Internet 2.0. Company. Only one US organization was mentioned in the leak: the Center for Foreign Policy Studies which likely refers to a center by that name affiliated with Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey. In contrast, the i-SOON indictment alleges that i-SOON targeted a range of US victims, including:

Two New York City-based newspapers, including one that publishes news related to China and is opposed to the Chinese Communist Party;

The US Defense Intelligence Agency, Department of Commerce and International Trade Administration;

A religious organization with millions of members and tens of thousands of affiliated churches and congregations;

A Texas-based organization that promotes human rights and religious freedom in China;

The New York State Assembly;

A State research university; and

A Washington D.C.-based news service that "delivers uncensored domestic news to audiences in Asian countries, including China."

In the leaked documents, the Natto Team discovered that an i-SOON employee complained in a chat that their access to a US target had been lost. Another employee said, “It’s normal. That’s why (we) hardly ever target US targets because it is so easy to lose access and easy to be exposed.” So, it seems i-SOON hackers were not yet good enough to maintain backdoors in US targets. Well, this might have not always been the case; judging from the indictment, i-SOON was pretty impressive to choose or be tasked with targeting US entities.

For a CTI analyst, source evaluation and information reliability are a constant quest in threat research. Leaks or indictments rarely align in a particular case, but the most important thing is to compare and assess those facts that are not aligned.

Natto Thoughts is a reader-supported publication. Your paid subscription supports access for all and serves as a token of appreciation for the efforts of the Natto Team

Note: indictments from US federal law enforcement are highly vetted by agents and prosecutors who traditionally adhered to long-held norms of even-handed investigation and due process, rigorous rules for the collection and handling of evidence, safeguards for the presumption of innocence of defendants, and professional incentives to ensure that the allegations are likely to stand up under cross-examination in front of a jury and not be overturned on appeal. Indictments are explicitly identified as allegations only, until proven in court. US federal law enforcement bodies have traditionally had procedures to identify and remediate deviations from these norms. Some critics of various political persuasions have nevertheless claimed “weaponization” of the justice system.

Introduction to Malware Binary Triage (IMBT) Course

Looking to level up your skills? Get 10% off using coupon code: MWNEWS10 for any flavor.

Enroll Now and Save 10%: Coupon Code MWNEWS10

Note: Affiliate link – your enrollment helps support this platform at no extra cost to you.

Article Link: Indictments and Leaks: Different but Complementary Sources