This didn’t start as a blog post. It started as a conversation with Hari Charan @grep_security about something they were looking at called SunCrypt ransomware.

Looking up the name I ran across a couple of interesting blog post, one by Sapphire here and one by Acronis here . Seeing that this was obfuscated PowerShell it peaked my interest.

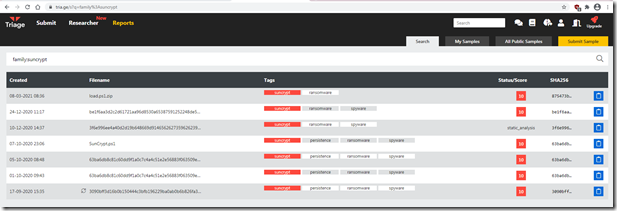

Searching for some samples to work with also revealed that you can do a tag search on tri.age of “family: suncrypt” (without the space)

The PowerShell loader we are going to use here is the one from the Acronis blog post with a hash of MD5: d87fcd8d2bf450b0056a151e9a116f72 . There are multiple copies on https://app.any.run/submissions/ for that hash. There are 3 copies on Tri.age here.

Hari Charan @grep_security also pointed me to a couple of open source yara rules to search for the PowerShell loaders.

This one appears as though it will search for the ransomware binary here and this one will search for the PowerShell script here .

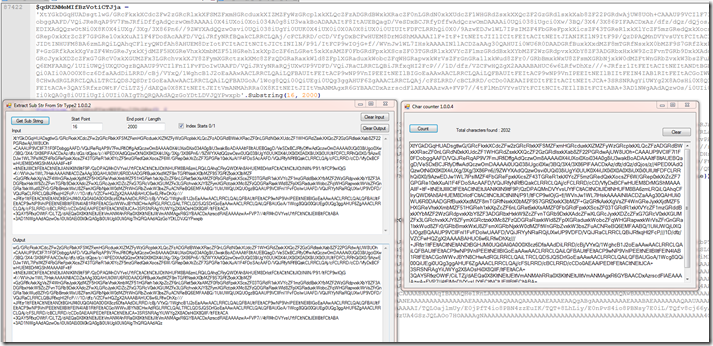

Let’s take a look at some of the encoding.

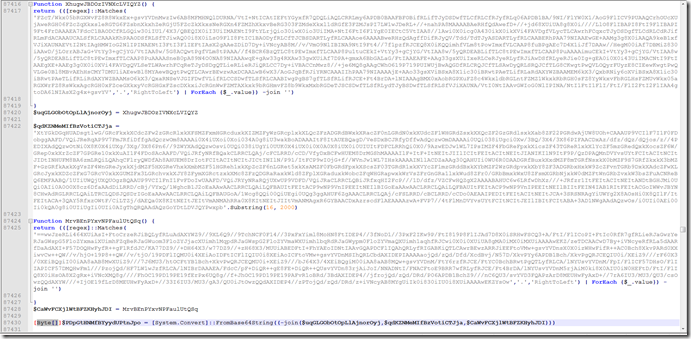

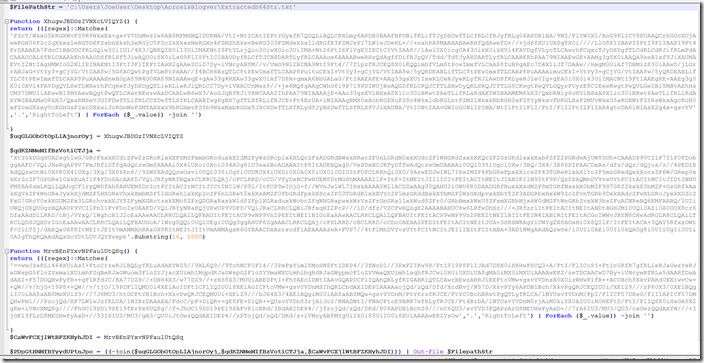

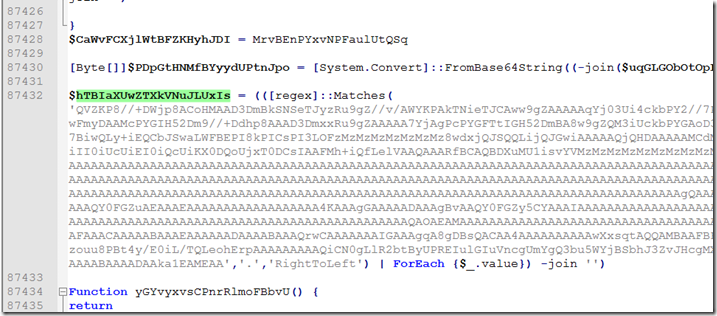

If we look at this part it takes 3 values , assembles them , then it base64 decodes to byte.

But it will also do something to the strings before it reassembles them.

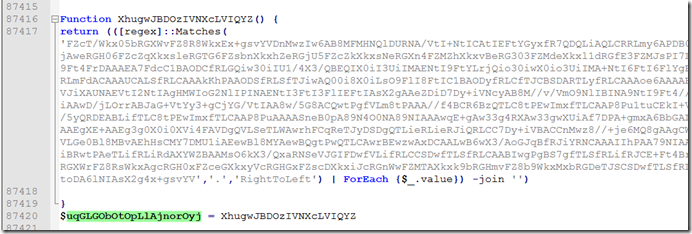

We can see the first string is redirected to a function that will read right to left , basically just reverse the string.

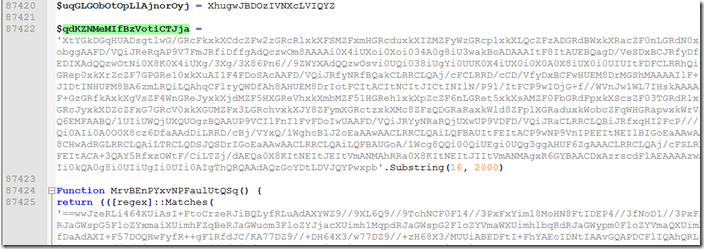

If we Look at the second string it is getting a substring of what is there starting at index 16 and taking 2000 characters.

The encoded string is actually 2032 characters long before we get the substring.

The final string is is just another reverse string.

Then we just have a long base 64 string after reassembling the pieces.

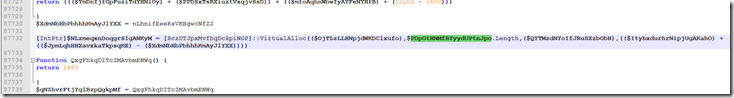

Remember we still have to convert this to byte and it will get loaded into memory using VirtualAlloc.

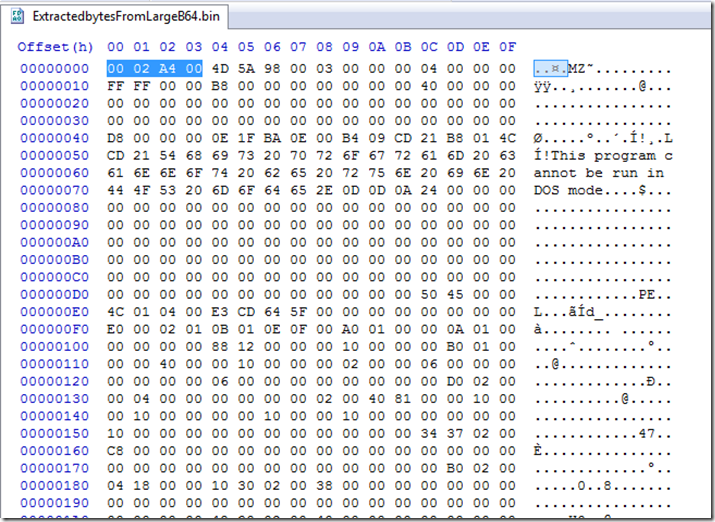

Looking at the bytes in a hex editor we can not see anything that makes any sense.

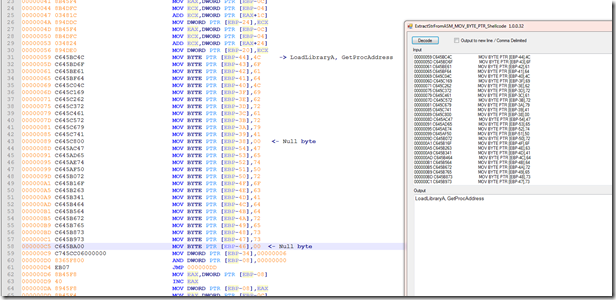

The next step is to drop this into CyberChef here and view the assembly.

This is also where I hinted on Twitter of a “Somewhat useful tool” which will be on my Github.

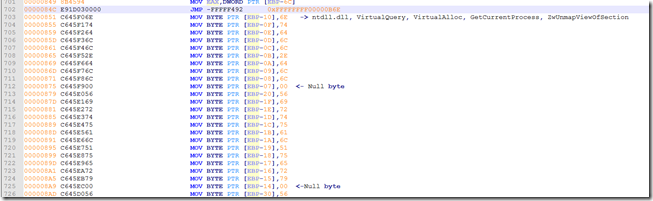

If we look down further we see more API calls.

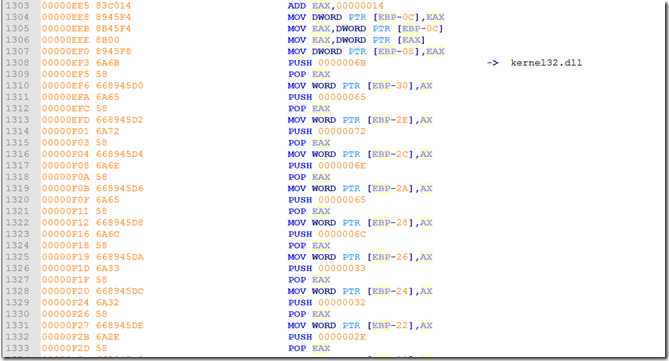

And even further down we see a different type of string building using a “push pop”. I have not made a tool for that yet.

Although doing this statically we can not tell for sure how this is used it can give some clues as to what it will be doing by the API calls.

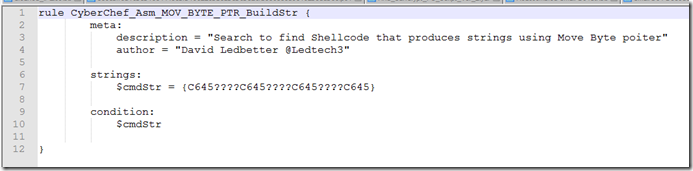

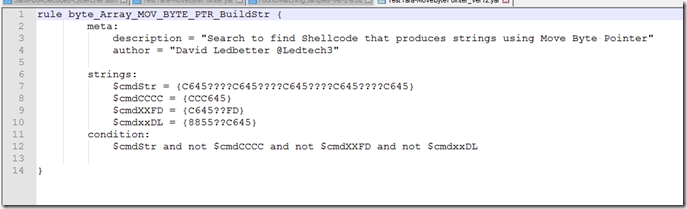

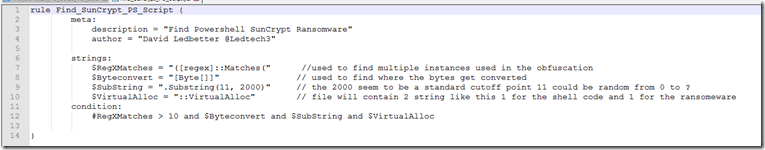

What started all of this was when I was trying to write a yara rule to find more samples to test this tool with and look for any outliers that would break it or not be what I was looking for.

I’m still learning yara and this version just looked for the format of the “MOV BYTE PTR”.

I ended up with over 552 hits for this and many false positives. I knew I need to find something to rule out some of the values that did not return strings or would return either encoded or garbage looking strings.

After several hours of trial and error I ended up with this.

That reduced it down to 214 hits. It ended up being shellcode and binary samples that used that format. I’m sure there are a few more samples in that mix that would be false positives but it was good enough for what I wanted.

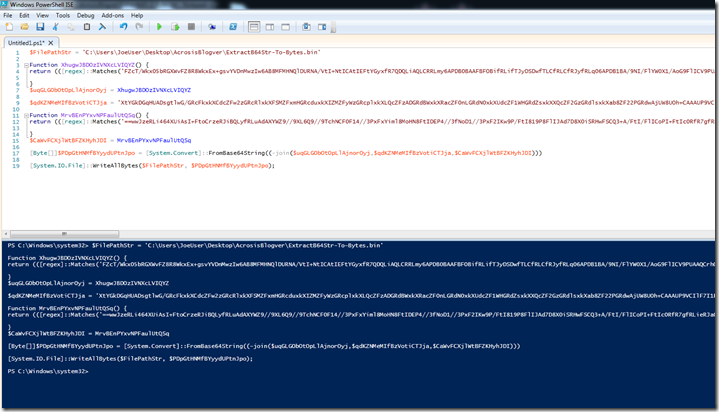

After going thru that exercise I was wanting to try and find a way to let the obfuscated PowerShell self decode. So I started by looking for a way to just let it reassemble the base64 string and then write that to a file.

The template part is the path variable and the pipe out to file. But you have to remember to remove the “[Byte[]]” part and the “[System.Convert]::FromBase64String” from each one you wanted to rebuild and just dump to a text file for further processing of the base64 string.

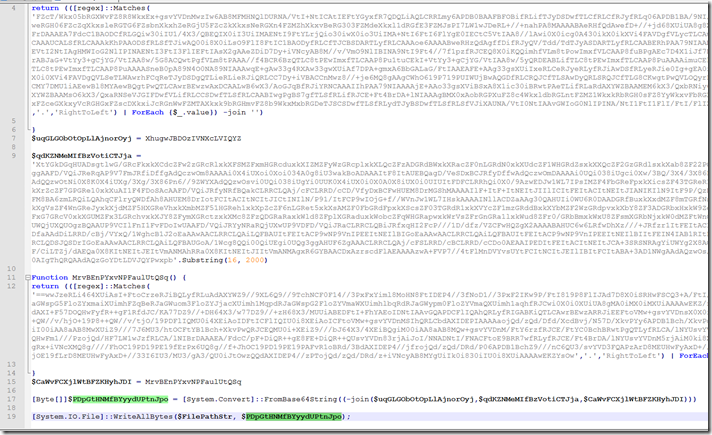

So I then went back and searched for how to just output to a binary file since that is what we ultimately wanted anyway..

The variable for the path can be the same but instead of pipe to write file / text we add the line with the System IO and make sure we have the variable name the same as in the extracted PowerShell.

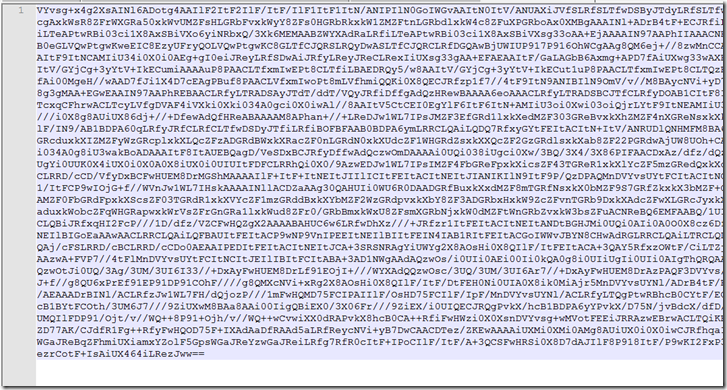

Moving on to the large base64 string.

Using Notepad++ we notice the highlighted area is all 1 section. You may also notice the extra parameter name right after the join.

Searching for that value we find it all the way up right after the code for the shellcode reassembling.

So when we go to use the self decode trick we need from here all of the way to the end of the highlighted area to be sure we have all of the needed parameters to rebuild the base64 string before it gets decoded to hex/binary data.

Once we drop this into our wrapper and verify we have the proper output name set we can then just input it into the PowerShell ISE and run it and it will output our binary file for the next step.

Now the first four bytes of this output appears to be a length of the remaining bytes in the output. These will need to be removed for the next step.

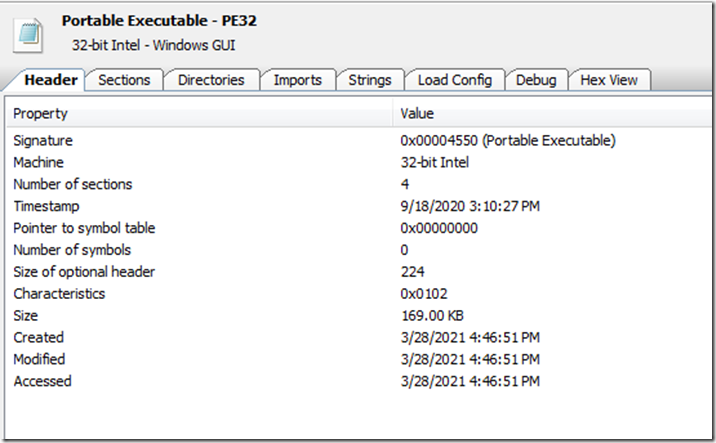

Here we see it is a 32 bit binary with a Timestamp of 9/18/2020 although the file was assembled today in the created date.

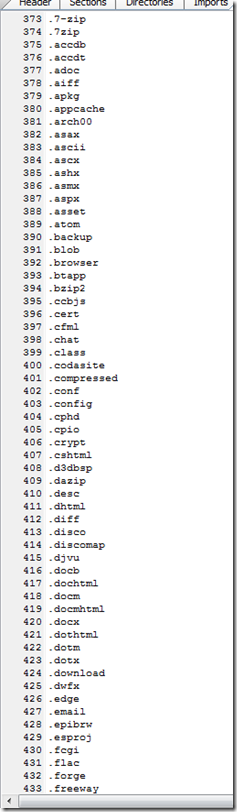

If we look at the Unicode strings we can see that file extension strings are not obfuscated or hashed like the other blog post showed.

One of the next things I was looking for is how to extract the ransom Note.

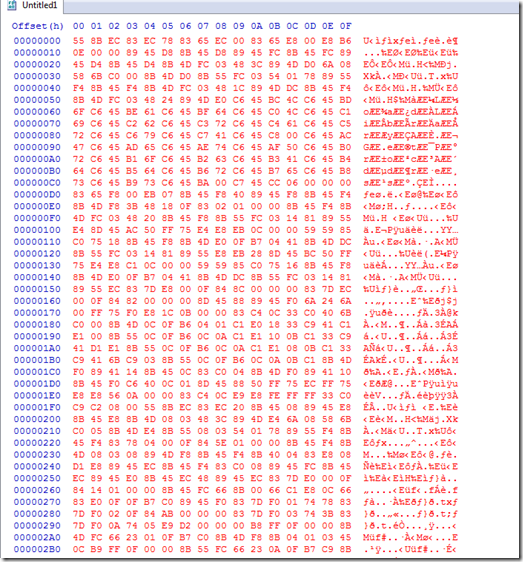

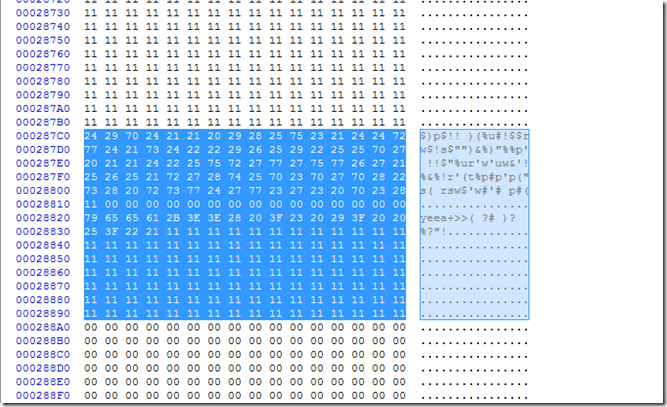

The other Blog post gives us clues what we are looking for so lets look at the file in a hex editor.

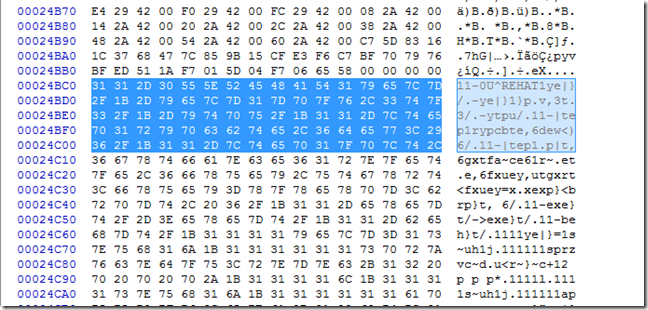

There is a very distinctive string that begins with “11” as it turn out “0x11” is the xor key.

One of the other samples used 0x13 for the xor key.

If we scroll down to the end we can see clearly where this section will end.

If we keep scrolling down while we still have multiple “11” values we get to this.

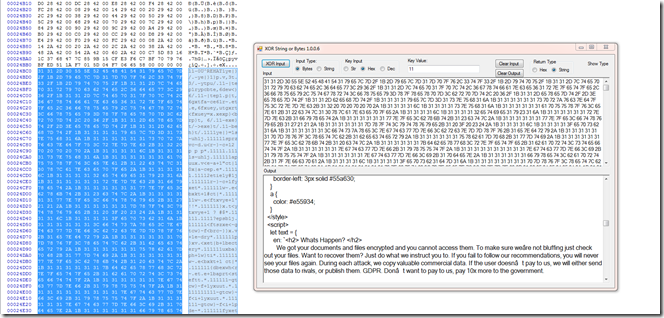

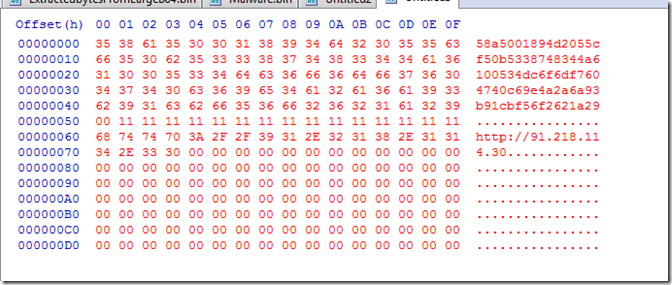

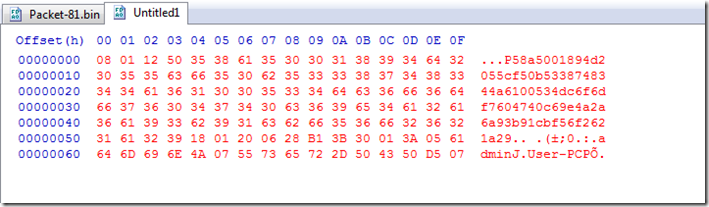

If we xor that by 0x11 we get this.

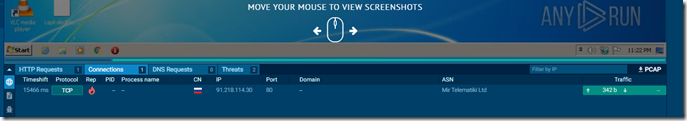

Next I upped this to Anyrun here because I could not figure out at the time where the ip was coming from.

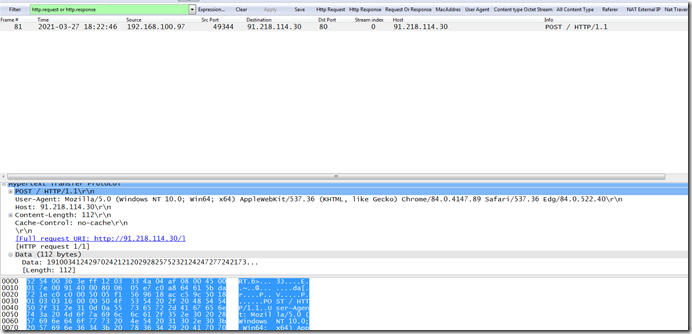

One of the last pieces of this puzzle is that it does a post request with some encoded data.

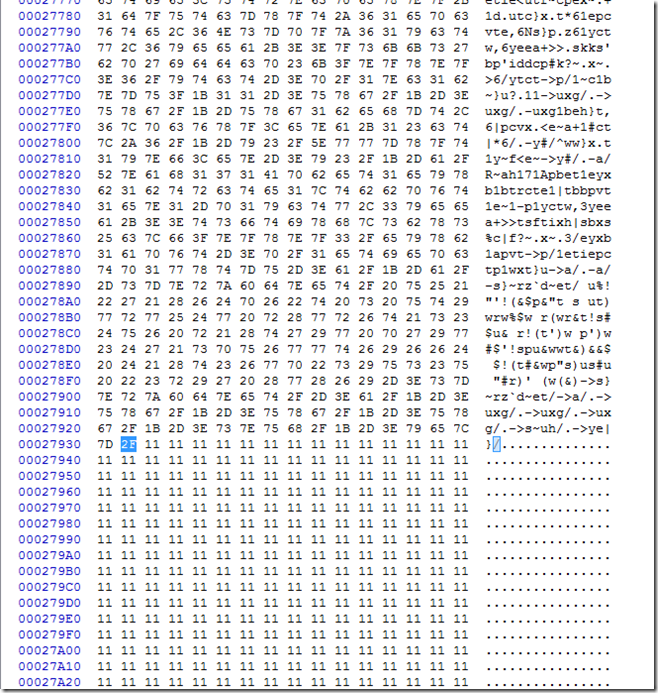

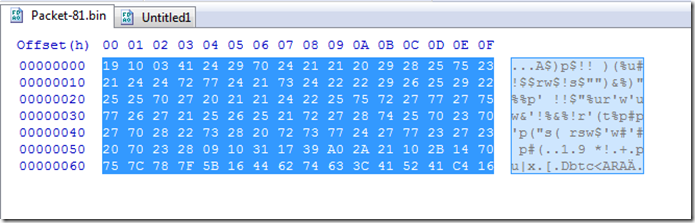

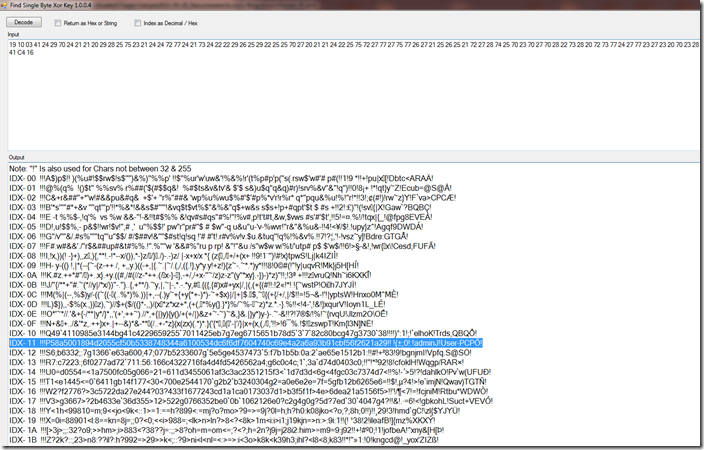

If we look at the data that gets dumped from the packet we see this.

So as a guess I checked to see if it had a single byte xor key and to my surprise it did.

The same one as the rest to decode with, 0x11.

Does this passed hex value look familiar ? It is from the section where the IP was extracted.

What is it? I do not know. If someone does please let me know.

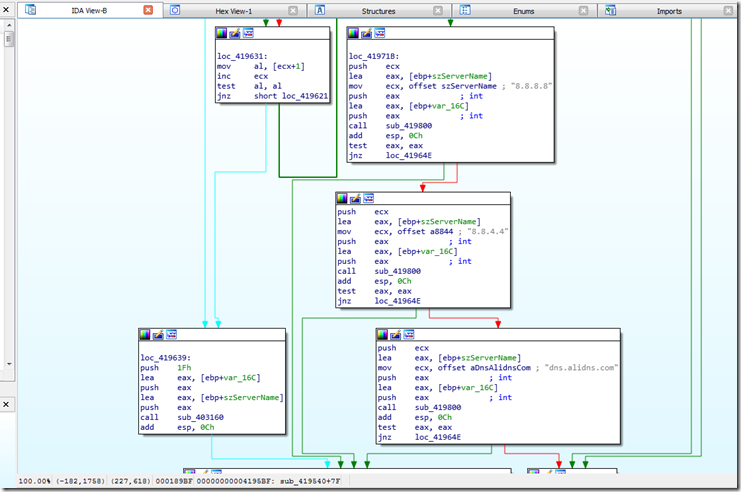

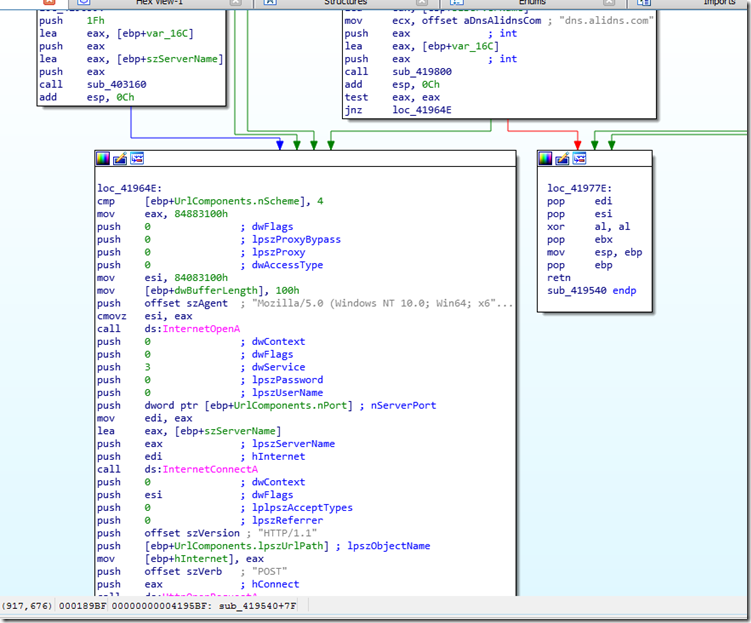

One other thing while I was not initially able to find the IP, I dropped this into IDA to see if I could figure out how it worked.

Seeing this ..

And this..

Was still no help to figure out what was passed.

I’m sure the IDA Experts could tease out the information quick but that is something else I still need to learn.

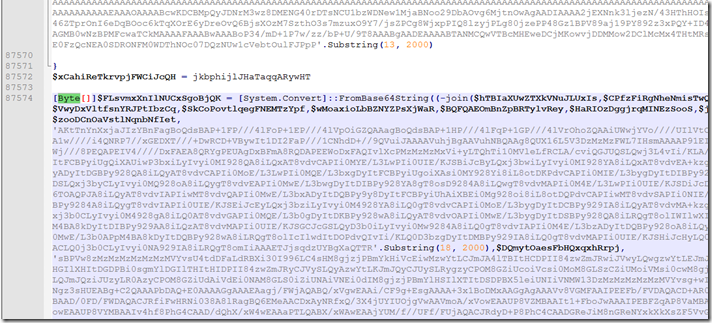

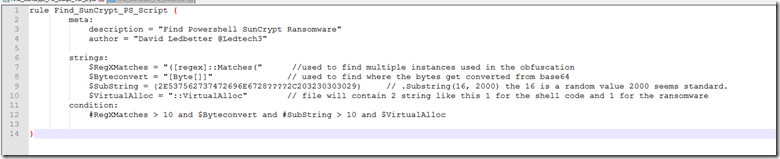

While working on this and needing more samples to compare I also wrote a yara rule to detect the obfuscation format. The open source one will detect the base 64 encoding method.

This first version will search for substring as a string and only has to be found once since the value is “11” in the string.

This version will search for the “Substring” string as bytes but allow for multiple possible values in the start point for the substring.

Well that is pretty much as far I can go on this.

Possible future research.

Set up a vm with Sysmon and PowerShell logging enabled as suggested by Lee Holmes here and run the sample to see what the logs will show me.

Take a closer look and learn how the encryption works.

Links:

Link to Acronis Blog post

Link to Sapphire Blog post

Link to Anyrun for the extracted ransomware

Link to Anyrun for PowerShell sample

Link to tri.age Search

Link to my Github for Files

Link for open source yara rule for the binary

Link for open source yara rule for finding the PowerShell script

Link for working with CyberChef Assembly

Article Link: https://pcsxcetrasupport3.wordpress.com/2021/03/28/suncrypt-powershell-obfuscation-shellcode-and-more-yara/