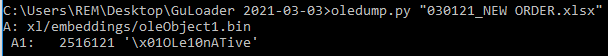

I came across a GuLoader .xlsx document the other day. It didn’t have any VBA or XLM macros, locked or hidden or protected sheets, or anything obvious like that. Instead, this is the only thing I saw in oledump.

It was a bit odd. So let’s see what it takes to tear apart a document such as this. If you’d like to play along, here’s the specimen: https://app.any.run/tasks/706a2ec9-c993-40e0-811a-b18358531b24

A special shout out to @ddash_ct! He helped point me in the right direction for extracting the shellcode.

oleObject1.bin

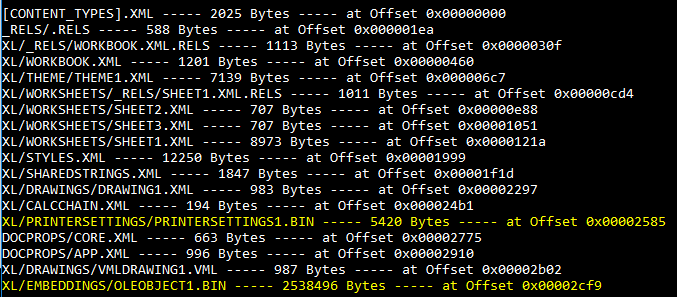

Upon unzipping the file, we can find oleobject1.bin inside the XL/EMBEDDINGS folder.

If you will recall, OLE stands for Object Linking and Embedding. Microsoft documents allow a user to link or embed objects into a document. An object that is linked to a document will store that data outside of the document. If you update the data outside of the document, the link will update the data inside of your new document.

An embedded object becomes a part of the new file. It does not retain any sort of connection to the source file. This is perfect way for attackers to hide or obfuscate code inside a malicious document.

OLe10nATive stream

oledump.py showed that the oleObject1.bin contained a stream called OLe10nATive. These are the storage objects that correspond to the linked or embedded objects. That stream is present when data from the embedded object in the container document in OLE1.0 is converted to the OLE2.0 format.

We can extract this stream by using oledump to select object A1 and dump it to a file.

Looking for shellcode

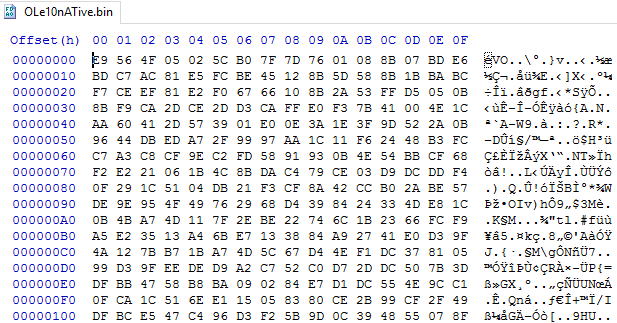

Now that we’ve extracted the stream, how are we going to find anything useful in here?

This is where the advice from @ddash_ct came in handy. He searched this stream output for a hex string like E8 00 00 00 00 and was able to extract the shellcode from there.

Why is this the case? And why that pattern?

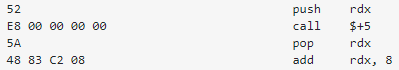

Shellcode cannot assume it will be executed in any particular memory location. It cannot use any hard-coded addresses for either its code or data. This means it must be position-independent. A hex string such as E8 00 00 00 00 can be an indicator of where position-independent code may start. While the example below is not from our sample, the opcode E8 00 00 00 00 is translated into the instruction call $+5. This is used to push the current address in memory onto the stack. This can serve as a sort of anchor point for the rest of the code execution.

This is just an example and is not from the ole10native stream in our sample.

This is just an example and is not from the ole10native stream in our sample.

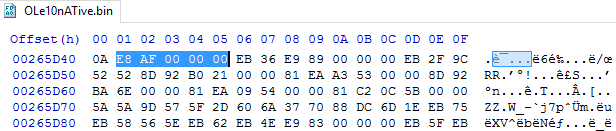

We will not find the exact E8 00 00 00 00 pattern in our file. Instead, we can search for a pattern like 00 00 and something interesting pops up at 0x00265D41.

While we do see a similar pattern, there is a significant difference. The opcode E8 is making a call and will be transferring control to location 0x000000AF. However, the location of AF is relative to E8’s position in memory at run-time. It seems we may have an instance of position-independent code and it might be where some shellcode is hiding. Got that?

All this is to say that hex location 0x265D41 is a likely candidate for our purposes.

Extracting the shellcode

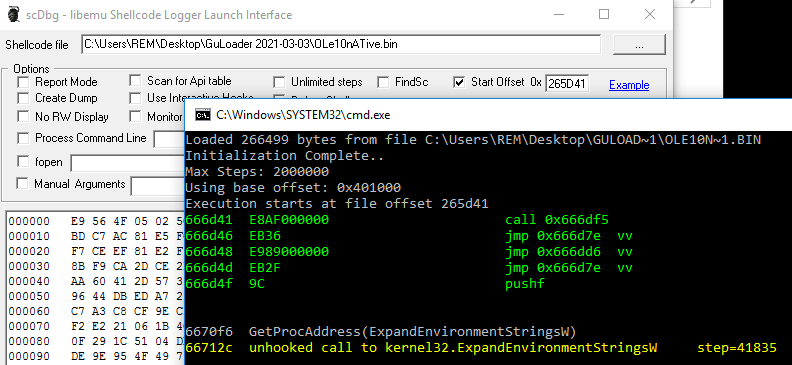

From here on out, this will be a very similar process to getting shellcode from .rtf documents. We can load up ole10native.bin in scDbg with a start offset of 0x265D41. We know we’re on the right track because we can see the unhooked call to ExpandEnvironmentStringsW.

Earlier blog posts showed that scDbg doesn’t work very well with ExpandEnvironmentStringsW. Instead, we can overwrite that with ExpandEnvironmentStringsA. To do so, we will need to unpack ole10native.bin. We do that by checking the box in scDbg for “Create Dump” and re-launch ole10native.bin using the same start offset of 0x265D41. scDbg will then save the dumped and unpacked file. In my case, it was called OLE10N~1.unpack.

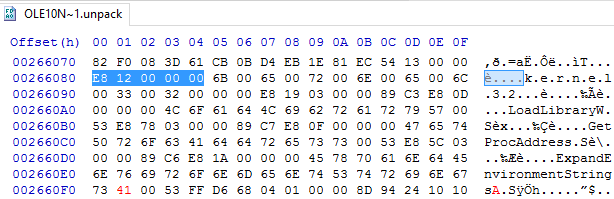

Open up the newly unpacked dump file and scroll to the bottom. You will see a variety of commands in plaintext. Offset 0x002660D9 begins the command for ExpandEnvironmentStringsW. Overwrite the appropriate location with an A and save the changes.

Before we toss this into scDbg again, we are going to need a new start offset. This can be found at the beginning of this part of the shell code. Notice the pattern right before k.e.r.n.e.l.3.2. It also follows the E8 00 00 00 00 pattern.

Toss our unpacked and edited binary into scDbg and enter 0x00266080 as the start offset. And when we do, the shellcode commands are revealed.

Thanks for reading!

References

https://support.microsoft.com/en-us/office/linked-objects-and-embedded-objects-0bf81db2-8aa3-4148-be4a-c8b6e55e0d7c

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/openspecs/windows_protocols/ms-oleds/2677fcf2-ad48-4386-ba8f-b1b7baf4c02f

https://www.forcepoint.com/blog/x-labs/assessing-risk-office-documents-part-2-hide-my-code-or-download-it

Practical Malware Analysis (the book)

Article Link: https://clickallthethings.wordpress.com/2021/03/06/oleobject1-bin-ole10native-shellcode/