This blogpost is a follow-up to a presentation with the same name, given at SecurityFest in Sweden by Alfred Klason.

Summary

Bokbot (aka: IcedID) came to Fox-IT’s attention around the end of May 2017 when we identified an unknown sample in our lab that appeared to be a banker. This sample was also provided by a customer at a later stage.

Having looked into the bot and the operation, the analysis quickly revealed that it’s connected to a well-known actor group that was behind an operation publically known as 76service and later Neverquest/Vawtrak, dating back to 2006.

Neverquest operated for a number of years before an arrest lead to its downfall in January 2017. Just a few months afterwards we discovered a new bot, with a completely new code base but based on ideas and strategies from the days of Neverquest. Their business ties remains intact as they still utilize services from the same groups as seen before but also expanded to use new services.

This suggests that at least parts of the group behind Neverquest is still operating using Bokbot. It’s however unclear how many of the people from the core group that have continued on with Bokbot.

Bokbot is still a relatively new bot, just recently reaching a production state where they have streamlined and tested their creation. Even though it’s a new bot, they still have strong connections within the cybercrime underworld which enables them to maintain and grow their operation such as distributing their bot to a larger number of victims.

By looking back in history and the people who are behind this, it is highly likely that this is a threat that is not going away anytime soon. Fox-IT rather expects an expansion of both the botnet size and their target list.

76service and Neverquest

76service was, what one could call, a big-data mining service for fraud, powered by CRM (aka: Gozi). It was able to gather huge amounts of data from its victims using, for example, formgrabbing where authorization and log-in credentials are retrieved from forms submitted to websites by the infected victim.

76service login page (source: krebsonsecurity.com)

The service was initially spotted in 2006 and was put into production in 2007, where the authors started to rent out access to their platform. When given access to the platform, the fraudulent customers of this service could free-text search in the stolen data for credentials that provide access to online services, such as internet banking, email accounts and other online platforms.

76service operated uninterrupted until November 2010, when an Ukrainian national named Nikita Kuzmin got arrested in connection with the operation. This marked the end of the 76service service.

Nice Catch! – The real name of Neverquest

A few months before the arrest of Nikita he shared the source code of CRM within a private group of people which would enable them to continue the development of the malware. This, over time, lead to the appearance of multiple Gozi strains, but there was one which stood out more than the others, namely: Catch.

Catch was the name given internally by the malware authors, but to the security community and the public it was known as Vawtrak or Neverquest.

During this investigation into Catch it became clear that 76service and Catch shared several characteristics. They both, for example, separated their botnets into projects within the panel they used for administering their infrastructure and botnets. Instead of having one huge botnet, they assigned every bot build with a project ID that would be used by the bot to let the Command & Control (C2) server know which specific project the bot belonged to.

76service and Catch also shared the same business model, where they shifted back and forth between a private and rented model.

The private business model meant that they made use of their own botnet, for their own gain, and the rented business model meant that they rented out access to their botnet to customers. This provided them with an additional income stream, instead of only performing the fraud themselves.

The shift between business models could usually be correlated with either: backend servers being seized or people with business ties to the group being arrested. These types of events might have spooked the group as they limited their infrastructure, closing down access for customers.

For the sake of simplicity, Catch will from here on be referred to as Neverquest in this post.

“Quest means business” – Affiliations

If one would identify a Neverquest infection it might not be the only malware that is lurking on the infected system. Neverquest has been known to cooperate with other crimeware groups, either to distribute additional malware or use existing botnets to distribute Neverquest.

During the investigation and tracking of Neverquest Fox-IT identified the following ties:

| Crimeware/malware group | Usage/functionality |

| Dyre | Download and execute Dyre on Neverquest infections |

| TinyLoader & AbaddonPOS | Download and execute TinyLoader on Neverquest infections. TinyLoader was later seen downloading AbaddonPOS (as mentioned by Proofpoint) |

| Chanitor/Hancitor | Neverquest leverages Chanitor to infect new victims. |

By leveraging these business connections, especially the connection with Dyre, Neverquest is able to maximize the monetization of the bots. This since Neverquest could see if a bot was of interest to the group and if not, it could be handed off to Dyre which could cast a wider net, targeting for example a bigger or different geographical region and utilize a bot in a different way.

More on these affiliations in a later section.

The never ending quest comes to an end

Neverquest remained at large from around 2010, causing huge amounts of financial losses, ranging from ticket fraud to wire fraud to credit card fraud. Nevertheless, in January 2017 the quest came to an end, as an individual named Stanislav Lisov was arrested in Spain. This individual was proven to be a key player in the operation: soon after the arrest the backend servers of Neverquest went offline, never to come back online, marking the end of a 6 year long fraud operation.

A more detailed background on 76service and Neverquest can be found in a blogpost by PhishLabs.

A wild Bokbot appears!

Early samples of Bokbot were identified in our lab in May 2017 and also provided to us by a customer. At this time the malware was being distributed to US infections by the Geodo (aka: Emotet) spam botnet. The name Bokbot is based on a researcher who worked on the very early versions of the malware (you know who you are  ).

).

Initial thoughts were that this was a new banking module for Geodo, as this group had not been involved in banking/fraud since May 2015. This scenario was quickly dismissed after having discovered evidence that linked Bokbot to Neverquest, which will be further outlined hereafter.

Bokbot internals

First, let’s do some housekeeping and look into some of the technical aspects of Bokbot.

Communication

All communication between a victim and the C2 server is sent over HTTPS using POST- and GET-requests. The initial request sent to the C2 is a POST-request containing some basic information about the machine it’s running on, as seen in the example below. Any additional requests like requesting configs or modules are sent using GET-requests, except for the uploading of any stolen data such as files, HTML code, screenshots or credentials which the victim submits using POST-requests.

Even though the above request is from a very early version (14) of the bot, the principle still applies to the current version (101), first seen 2018-07-17.

| URL param. | Comment |

| b | Bot identifier, contains the information needed to identify the individual bot and where it belongs. More information on this in later a section. |

| d | Type of uploaded information. For example screenshot, grabbed form, HTML or a file |

| e | Bot build version |

| i | System uptime |

| POST-data param. | Comment |

| k | Computer name (Unicode, URL-encoded) |

| l | Member of domain… (Unicode, URL-encoded) |

| j | Bot requires signature verification for C2 domains and self-updates |

| n | Bot running with privilege level… |

| m | Windows build information (version, arch., build, etc.) |

The parameters that are not included in the table above are used to report stolen data to the C2.

The C2 response of this particular bot version is a simple set of integers which tells the bot which command(s) that should be executed. This is the only C2 response that is unencrypted, all other responses are encrypted using RC4. Some responses are, like the configs, also compressed using LZMAT.

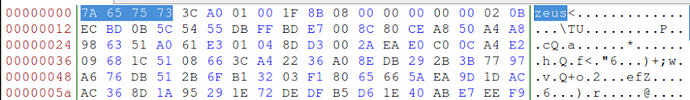

After a response is decrypted, the bot will check if the first 4 bytes equal “zeus”.

If the first 4 bytes are equal to “zeus”, it will decompress the rest of the data.

The reason for choosing “zeus” as the signature remains unknown, it could be an intentional false flag, in an attempt to trick analysts into thinking that this might be a new ZeuS strain. Similar elusive techniques have been used before to trick analysts. A simpler explanation could be that the developer simply had an ironic sense of humor, and chose the first malware name that came to mind as the 4 byte signature.

Configs

Bokbot supports three different types of configs, which all are in a binary format rather than some structured format like XML, which is, for example, used by TheTrick.

| Config | Comment |

| Bot | The latest C2 domains |

| Injects | Contains targets which are subject to web injects and redirection attacks |

| Reporting | Contains targets related to HTML grabbing and screenshots |

The first config, which includes the bot C2 domains, is signed. This to prevent that a takeover of any of the C2 domains would result in a sinkholing of the bots. The updates of the bot itself are also signed.

The other two configs are used to control how the bot will interact with the targeted entities, such as redirecting and modifying web traffic related to for example internet banking and/or email providers, for the purpose of harvesting credentials and account information.

The reporting config is used for a more generic purpose, where it’s not only used for screenshots but also for HTML grabbing, which would grab a complete HTML page if a victim browses to an “interesting” website, or if the page contains a specific keyword. This enables the actors to conduct some reconnaissance for future attacks, like being able to write web injects for a previously unknown target.

Geographical foothold

Ever since the appearance Bokbot has been heavily focused on targeting financial institutions in the US even though they’re still gathering any data that they deem interesting such as credentials for online services.

Based on Fox-IT’s observation of the malware spread and the accompanied configs we find that North America seems to be Bokbot’s primary hunting ground while high infection counts have been seen in the following countries:

- United States

- Canda

- India

- Germany

- Netherlands

- France

- United Kingdom

- Italy

- Japan

“I can name fingers and point names!” – Connecting the two groups

The two bots, on a binary level, do not show much similarity other than the fact that they’re both communicating over HTTPS and use RC4 in combination with LZMAT compression. But this wouldn’t be much of an attribution as it’s also a combination used in for example ZeuS Gameover, Citadel and Corebot v1.

The below tables provides a short summary of the similarities between the groups.

| Connection | Comment |

| Bot and project ID format | The usage of projects and the bot ID generation are unique to these groups along with the format that this information is communicated to the C2. |

| Inject config | The injects and redirection entries are very similar and the format haven’t been seen in any other malware family. |

| Reporting config | The targeted URLs and “interesting” keywords are almost identical between the two. |

| Affiliations | The two group share business affiliations with other crimeware groups. |

Bot ID, URL pattern and project IDs

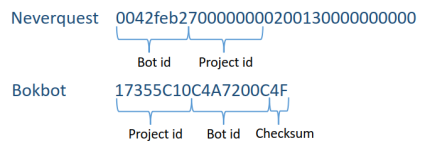

When both Neverquest and Bokbot communicate with their C2 servers, they have to identify themselves by sending their unique bot ID along with a project ID.

An example of the string that the server uses in order to identify a specific bot from its C2 communication is shown below:

The placement of this string is of course different between the families, where Neverquest (in the latest version) placed it, encoded, in the Cookie header field. Older version of Neverquest sent this information in the URL. Bokbot on the other hand sends it in the URL as shown in a previous section.

One important difference is that Neverquest used a simple number for their project ID, 7, in the example above. Bokbot on the other hand is using a different, unknown format for its project ID. A theory is that this could be the CRC checksum of the project name to prevent any leakage of the number of projects or their names, but this is pure speculation.

Another difference is that Bokbot has implemented an 8 bit checksum that is calculated using the project ID and the bot ID. This checksum is then validated on the server side and if it doesn’t match, no commands will be returned.

To this date there has been a total of 20 projects over 25 build versions observed, numbers that keeps on growing.

Inject config – Dynamic redirect structure

The inject config not only contain web injects but also redirects. Bokbot supports both static redirects which redirects a static URL but also dynamic redirects which redirects a request based on a target matched using a regular expression.

The above example is a redirect attack from a Neverquest config. They use a regular expression to match on the requested URL. If it should match they will extract the name of the requested file along with its extension. The two strings are then used to construct a redirect URL controlled by the actors. Thereby, the $1 will be replaced with the file name and $2 will be replaced with the file extension.

![]()

How does this compare with Bokbot?

Notice how the redirect URL contains $1 and $2, just as with Neverquest. This could of course be a coincidence but it should be mentioned that this is something that has only been observed in Neverquest and Bokbot.

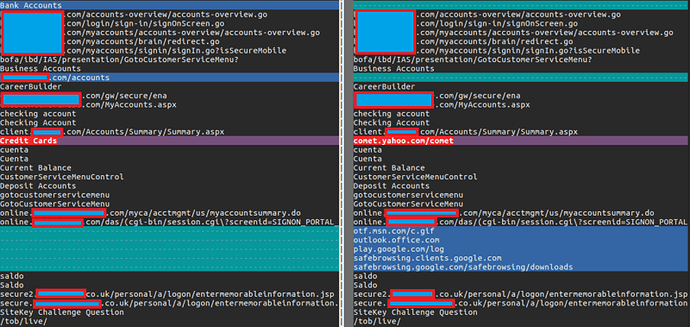

Reporting config

This config was one of the very first things that hinted about a connection between the two groups. By comparing the configs it becomes quite clear that there is a big overlap in interesting keywords and URLs:

Neverquest is on the left and Bokbot on the right. Note that this is a simple string comparison between the configs which also includes URLs that are to be excluded from reporting.

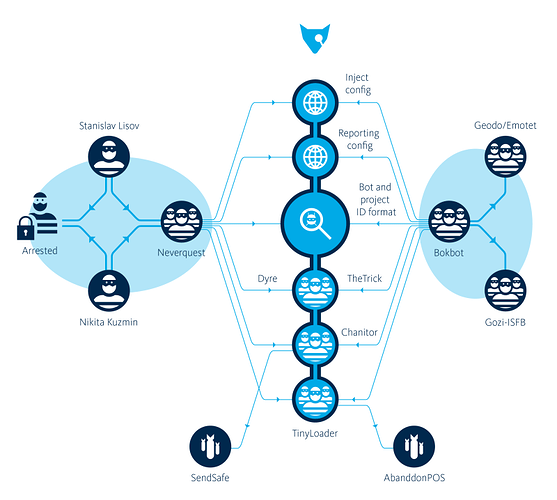

“Guilt by association” – Affiliations

None of these groups are short on connections in the cybercrime underworld. It’s already mentioned that Neverquest had ties with Dyre, a group which by itself caused substantial financial losses. But it’s also important to take into account that Dyre didn’t completely go away after the group got dismantled but was rather replaced with TheTrick which gives a further hint of a connection.

| Neverquest affil. | Bokbot affil. | Comment |

| Dyre | TheTrick | Neverquest downloads & executes Dyre |

| Bokbot downloads & executes TheTrick | ||

| TinyLoader | TinyLoader | Neverquest downloads & executes TinyLoader which downloads AbaddosPOS |

| Bokbot downloads & executes TinyLoader, additional payload remains unknown at this time | ||

| Chanitor | Chanitor | Neverquest utilizes Chanitor for distribution of Neverquest |

| Bokbot utilizes Chanitor for distribution of Bokbot, downloads SendSafe spam malware to older infections. | ||

| Geodo | Bokbot utilizes Geodo for distributing Bokbot | |

| Gozi-ISFB | Bokbot utilizes Gozi-ISFB for distributing Bokbot |

There are a few interesting observations with the above affiliations. The first is for the Chanitor affiliation.

When Bokbot was being distributed by Chanitor, an existing Bokbot infection that was running an older version than the one being distributed by Chanitor, would receive a download & execute command which pointed to the SendSafe spambot, used by the Chanitor group to send spam. Suggesting that they may have exchanged “infections for infections”.

The Bokbot affiliation with Geodo is something that cannot be linked to Neverquest, mostly due to the fact that Geodo has not been running its spam operation long enough to overlap with Neverquest.

The below graph show all the observed affiliations to date.

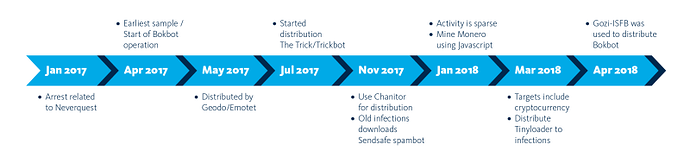

Events over time

All of the above information have been collected over time during the development and tracking of Bokbot. The events and observations can be observed on the below timeline.

The first occurrence of TheTrick being downloaded was in July 2017 but Bokbot has since been downloading TheTrick at different occasions.

At the end of December 2017 there was little Bokbot activity, likely due to the fact that it was holidays. It’s not uncommon for cybercriminals to decrease their activity during the turn of the year, supposedly everyone needs holidays, even cybercriminals. They did however push an inject config to some bots which targeted *.com with the goal of injecting Javascript to mine Monero cryptocurrency. As soon as an infected user visits a website with a .com top-level domain (TLD), the browser would start mining Monero for the Bokbot actors. This was likely an attempt to passively monetize the bots while the actors was on holiday.

Bokbot remains active and shows no signs of slowing down. Fox-IT will continue to monitor these actors closely.

Article Link: https://blog.fox-it.com/2018/08/09/bokbot-the-rebirth-of-a-banker/