A few weeks ago an ordinary security assessment turned into an incident response whirlwind. It was definitely a first for me, and I was kindly granted permission to outline the events in this blog post. This investigation started scary but turned out be quite fun, and I hope reading it will be informative to you too. I'll be back to posting about my hardware research soon.

- How it started

- What hell is this?

- The NFS Server

- 2nd malicious binary

- Further forensics

- Eureka Moment

- The GOlang thingy

- How the kernel got patched? and why not the golang app?

- What we have so far

- Q&A

How it started

Twice a year I am hired to do security assessments for a specific client. We have been working together for several years, and I had a pretty good understanding of their network and what to look for.

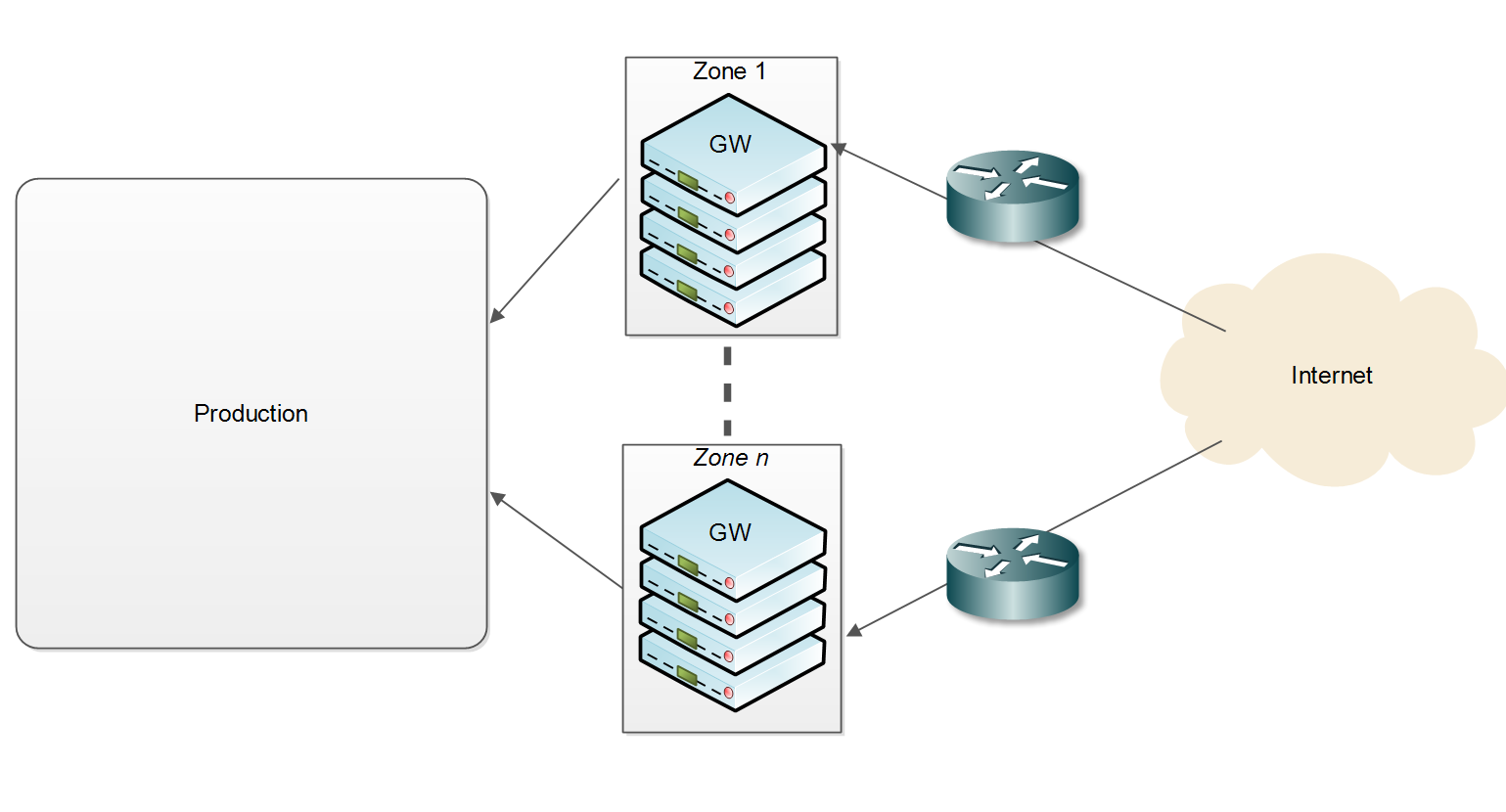

This time my POC, Klaus, asked me to focus on privacy issues and GDPR compliance. However, he asked me to first look at their cluster of reverse gateways / load balancers:

I had some prior knowledge of these gateways, but decided to start by creating my own test environment first.

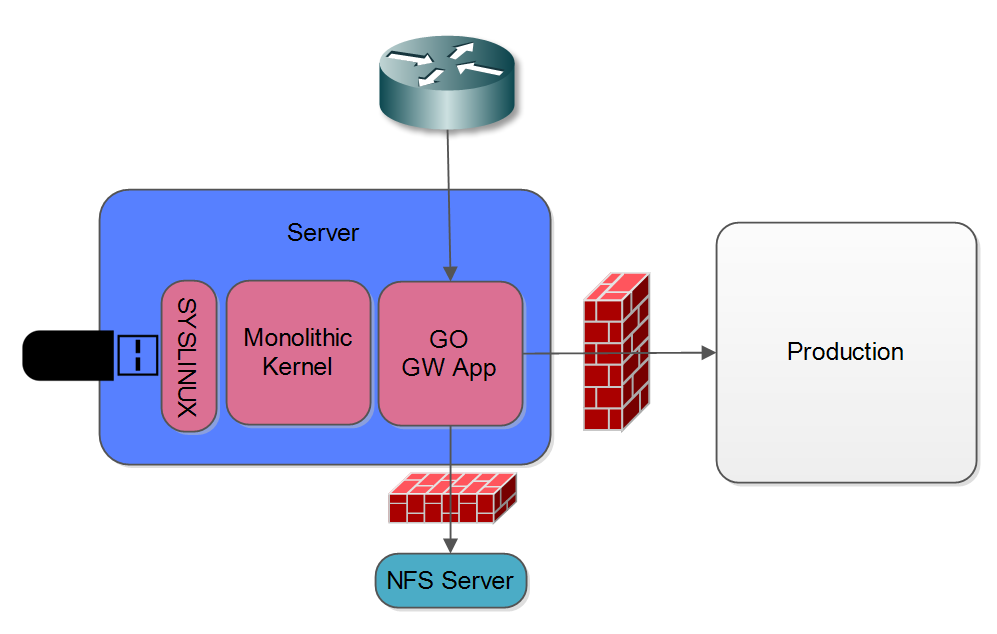

The gateways run a custom Linux stack: basically a monolithic compiled kernel (without any modules), and a static GOlang application on top. The 100+ machines have no internal storage, but rather boot from an external USB media that has the kernel and the application. The GOlang app serves in two capacities: an init replacement and the reverse gateway software. During initialization it mounts /proc, /sys, devfs and so on, then mounts an NFS share hardcoded in the app. The NFS share contains the app's configuration, TLS certificates, blacklist data and a few more. It starts listening on 443, filters incoming communication and passes valid requests on different services in the production segment.

I set up a self contained test environment, and spent a day in black box examination. Having found nothing much I suggested we move on to looking at the production network, but Klaus insisted I continue with the gateways. Specifically he wanted to know if I could develop a methodology for testing if an attacker has gained access to the gateways and is trying to access PII (Personally Identifiable Information) from within the decrypted HTTP stream.

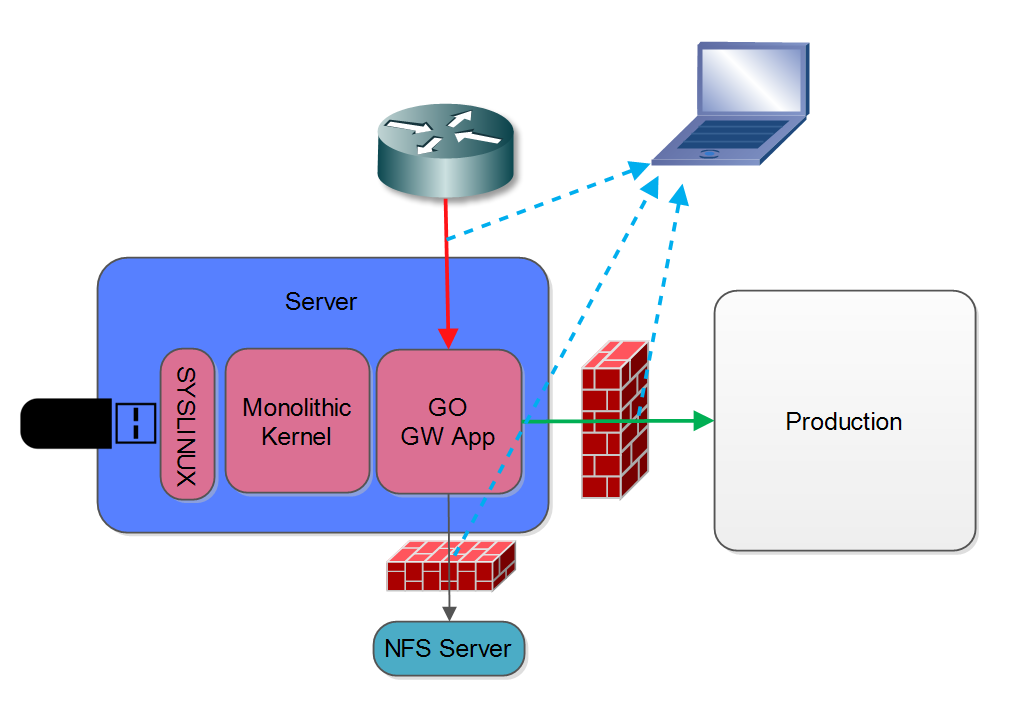

I couldn't SSH into the host (no SSH), so I figured we will have to add some kind of instrumentation to the GO app. Klaus still insisted I start by looking at the traffic before (red) and after the GW (green), and gave me access to a mirrored port on both sides so I could capture traffic to a standalone laptop he prepared for me and I could access through an LTE modem but was not allowed to upload data from:

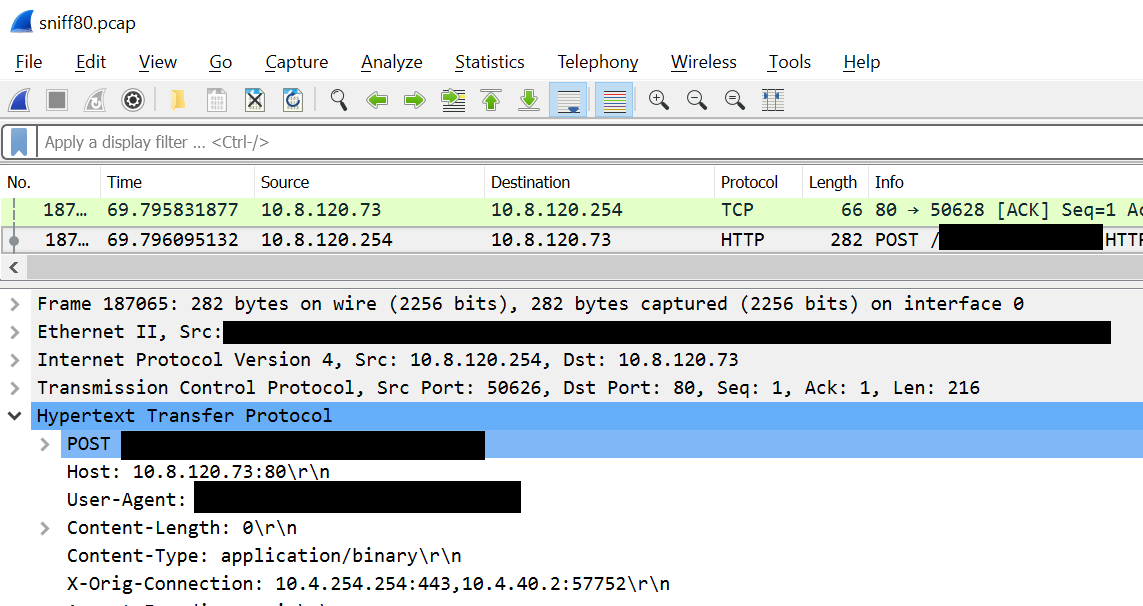

The problem I faced now was how to find out what HTTPS traffic corresponded to requests with embedded PII. One possible avenue was to try and correlate the encrypted traffic with the decrypted HTTP traffic. This proved impossible using timing alone. However, unspecting the decoded traffic I noticed the GW app adds an 'X-Orig-Connection' with the four-tuple of the TLS connection! Yay!

I wrote a small python program to scan the port 80 traffic capture and create a mapping from each four-tuple TLS connection to a boolean - True for connection with PII and False for all others:

10.4.254.254,443,[Redacted],43404,376106847.319,False

10.4.254.254,443,[Redacted],52064,376106856.146,False

10.4.254.254,443,[Redacted],40946,376106856.295,False

10.4.254.254,443,[Redacted],48366,376106856.593,False

10.4.254.254,443,[Redacted],48362,376106856.623,True

10.4.254.254,443,[Redacted],45872,376106856.645,False

10.4.254.254,443,[Redacted],40124,376106856.675,False

...

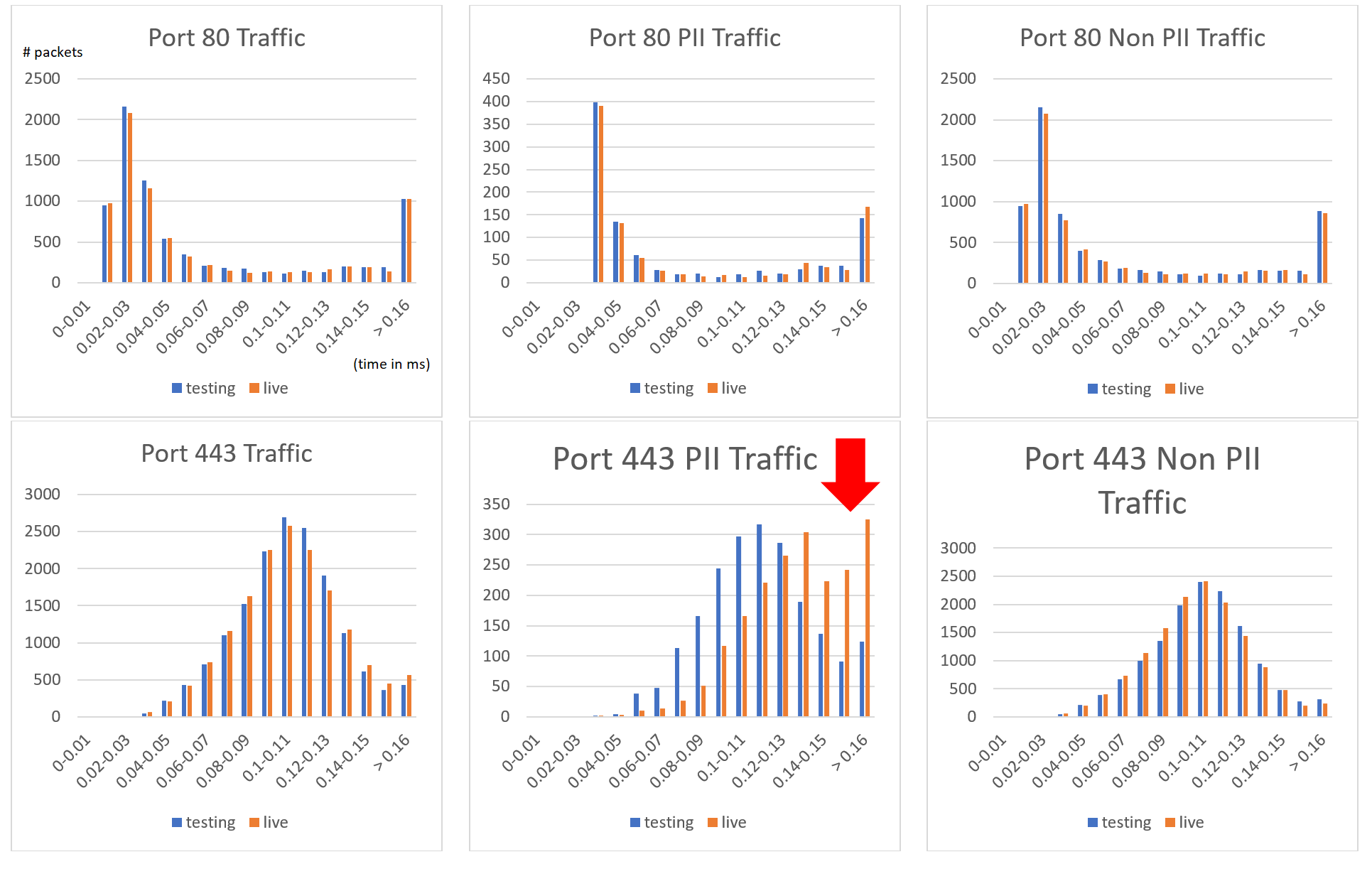

With this in mind I could now extract the data from the PCAPs and do some correlations. After a few long hours getting scapy to actually parse timestamps consistently enough for comparisons, I had a list of connection timing information correlated with PII. A few more fun hours with Excel and I got histogram graphs of time vs count of packets. Everything looked normal for the HTTP traffic, although I expected more of a normal distribution than the power-low type thingy I got. Port 443 initially looked the same, and I got the normal distribution I expected. But when filtering for PII something was seriously wrong. The distribution was skewed and shifted to longer time frames. And there was nothing similar on the port 80 end.

My only explanation was that something was wrong with my testing setup (the blue bars) vs. the real live setup (the orange bars). I wrote on our slack channel 'I think my setup is sh*t, can anyone resend me the config files?', but this was already very late at night, and no one responded. Having a slight OCD I couldn’t let this go. To my rescue came another security? feature of the GWs: Thet restarted daily, staggered one by one, with about 10 minutes between hosts. This means that every ten minutes or so one of them would reboot, and thus reload it’s configuration files over NFS. And since I could see the NFS traffic through the port mirror I had access to, I recokoned I could get the production configuration files from the NFS capture (bottom dotted blue line in the diagram before).

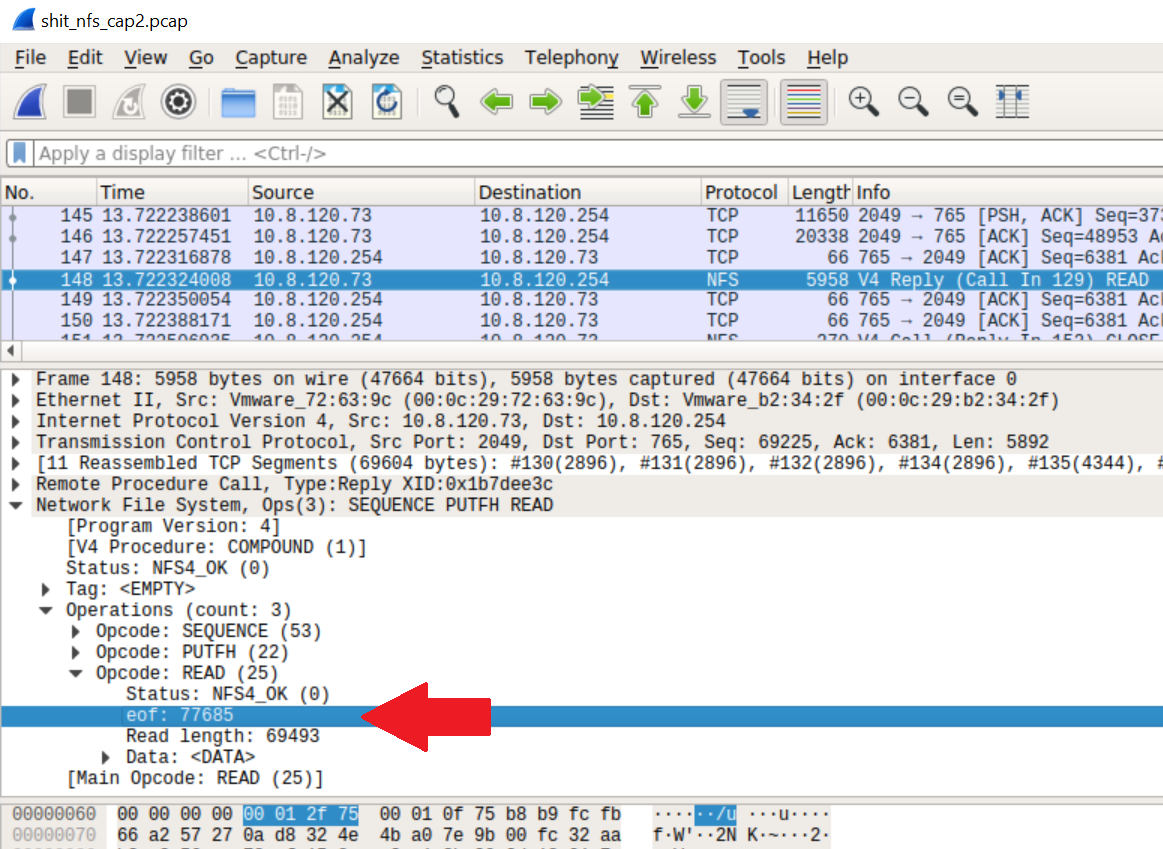

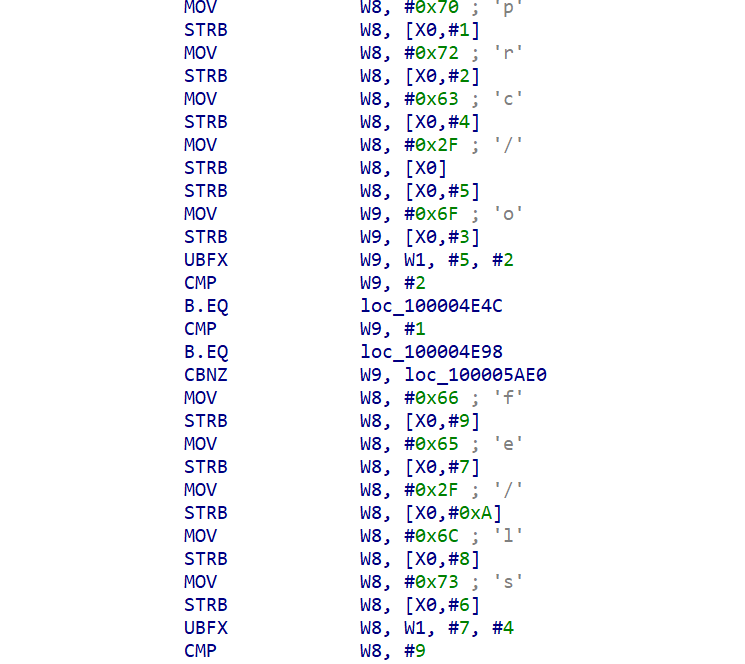

So to cut a long story short I found the NFS read reply packet, and got the data I need. But … why the hack is eof 77685??? Come on people, its 3:34AM!

What's more, the actual data was 77685 bytes, exactly 8192 bytes more then the ‘Read length’. The entropy for that data was pretty uniform, suggesting it was encrypted. The file I had was definitely not encrypted.

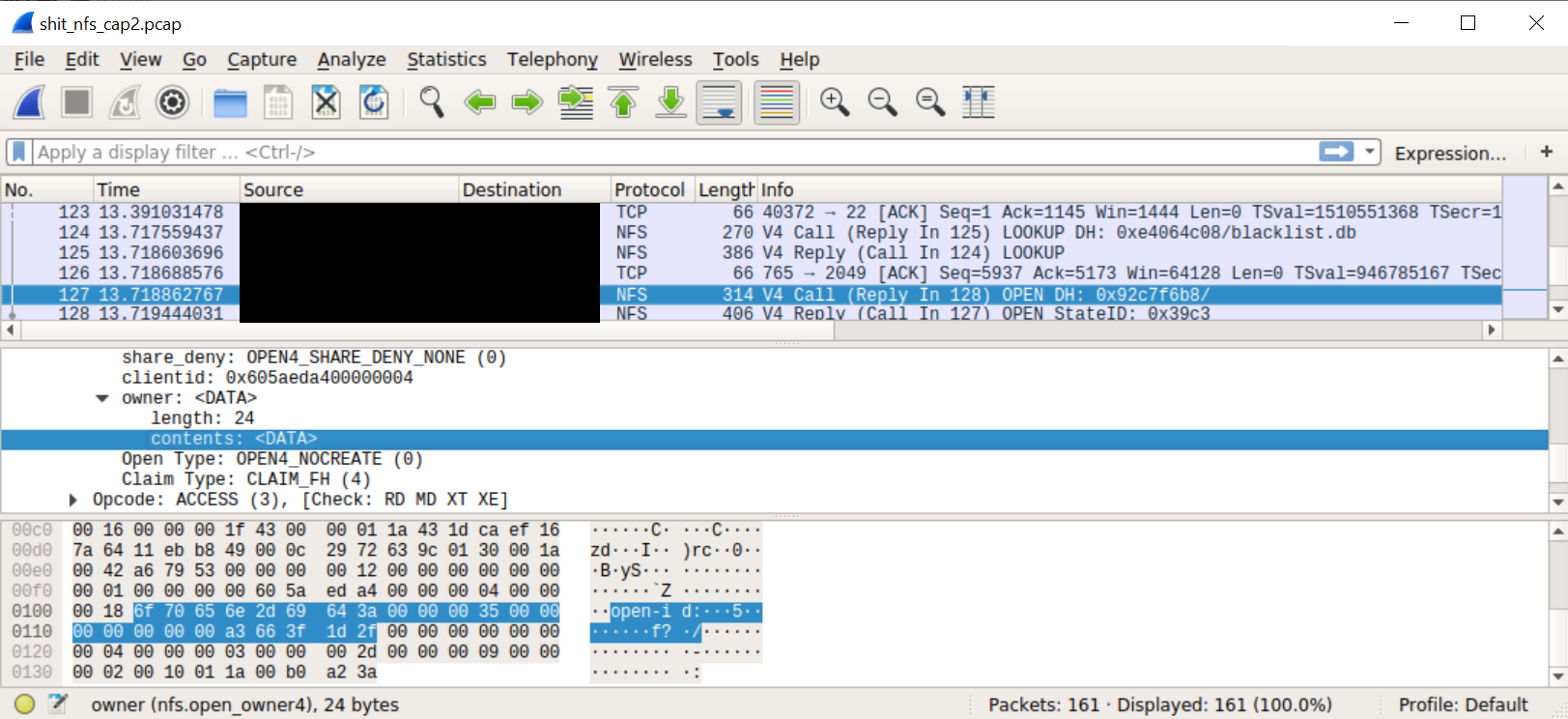

Histogram of extra 8192 bytes:

When I mounted the NFS export myself I got a normal EOF value of 1!

What hell is this?

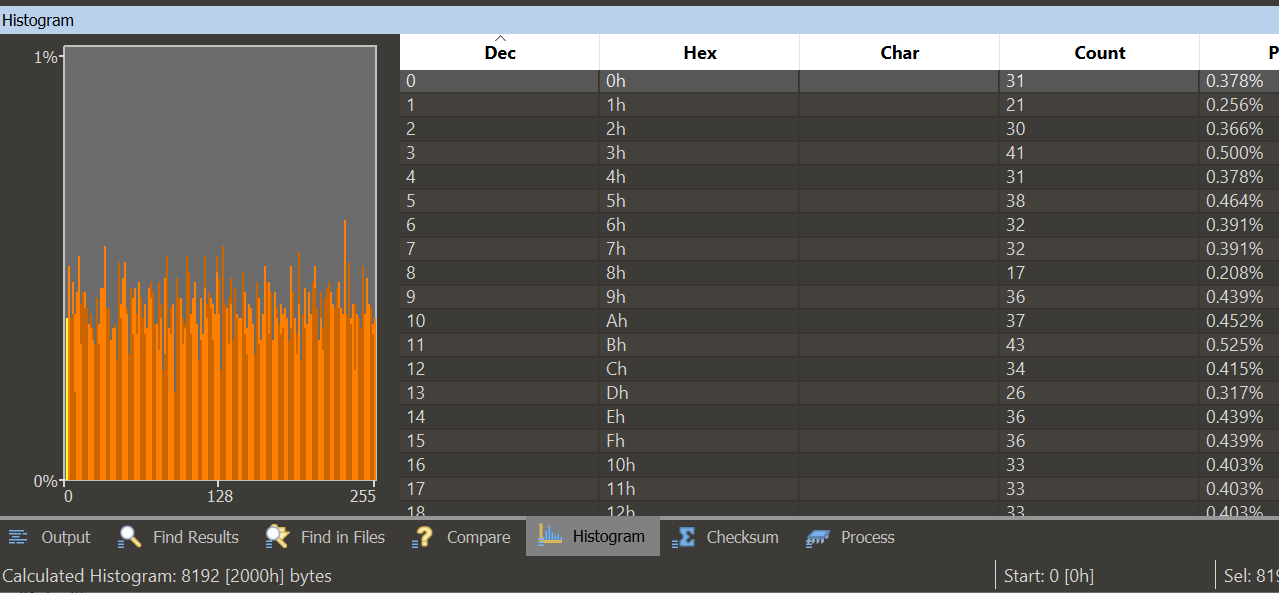

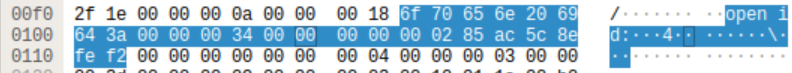

Comparing the capture from my testing machine with the one from the port mirror I saw something else weird:

For other NFS open requests (on all of my test system captures and for other files in the production system) we get:

Spot the difference?

The open id: string became open-id:. Was I dealing with some corrupt packet? But the exact same problem reappeared the next time blacklist.db was send over the wire by another GW host.

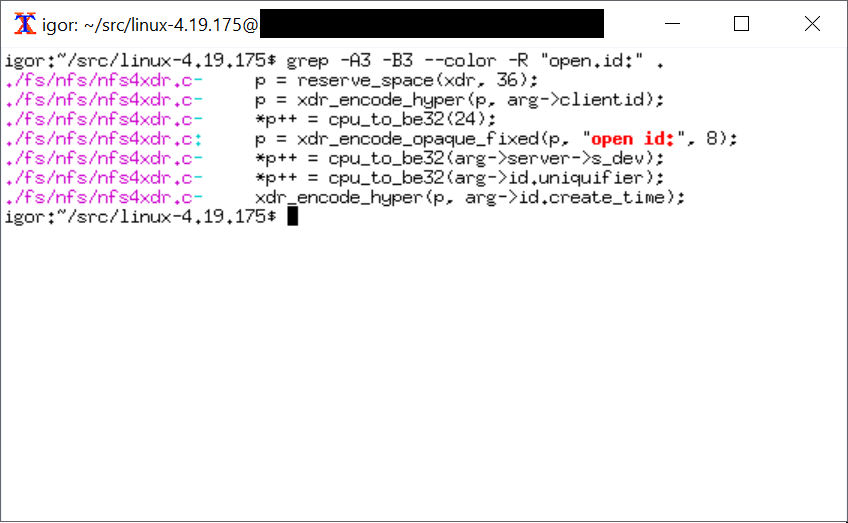

Time to look at the kernel source code:

The “open id” string is hardcoded. What's up?

After a good night sleep and no beer this time I repeated the experiment and convincing myself I was not hullucinating I decided to compare the source code of the exact kernel version with the kernel binary I got.

What I expected to see was this (from nfs4xdr.c):

static inline void encode_openhdr(struct xdr_stream *xdr, const struct nfs_openargs *arg)

{

__be32 *p;

/*

* opcode 4, seqid 4, share_access 4, share_deny 4, clientid 8, ownerlen 4,

* owner 4 = 32

*/

encode_nfs4_seqid(xdr, arg->seqid);

encode_share_access(xdr, arg->share_access);

p = reserve_space(xdr, 36);

p = xdr_encode_hyper(p, arg->clientid);

*p++ = cpu_to_be32(24);

p = xdr_encode_opaque_fixed(p, "open id:", 8);

*p++ = cpu_to_be32(arg->server->s_dev);

*p++ = cpu_to_be32(arg->id.uniquifier);

xdr_encode_hyper(p, arg->id.create_time);

}

Running binwalk -e -M bzImage I got the internal ELF image, and opened it in IDA. Of course I didn’t have any symbols, but I got nfs4_xdr_enc_open() from /proc/kallsyms, and from there to encode_open() which led me to encode_openhdr().

With some help from hex-rays I got code that looked very similiar, but with one key difference:

static inline void encode_openhdr(struct xdr_stream *xdr, const struct nfs_openargs *arg)

{

...

p = xdr_encode_opaque_fixed(p, unknown_func("open id:", arg), 8);

...

}

The function unknown_func was pretty long and complicated but eventually sometimes decided to replace the space between 'open' and 'id' with a hyphen.

Does the NFS server care? Apparently this string it is some opaque client identifier that is ignored by the NFS server, so no one would see the difference. That is unless they were trying to extract something from an NFS stream, and obviously this was not a likely scenario. OK, back to the weird 'eof' thingy from the NFS server.

The NFS Server

The server was running the 'NFS-ganesha-3.3' package. This is a very modular user-space NFS server that is implemented as a series of loadable modules called FSALs. For example support for files on the regular filesystem is implemented through a module called libfsalvfs.so.

Having verified all the files on disk had the same SHA1 as the distro package, I decided to dump the process memory. I didn't have any tools on the host, so I used GDB which helpfully was already there. Unexpectadly GDB was suddenly killed, the file I specified as output got erased, and the nfs server process restarted.

I took the dump again but there was nothing special there!

I was pretty suspicious at this time, and wanted to recover the original dump file from the first dump. Fortunately for me I was dumping the file to the laptop, again over NFS. The file had been deleted, but I managed to recover it from the disk on that server.

2nd malicious binary

The memory dump was truncated, but had a corrupt version of NFS-ganesha inside. There were two libfsalvfs.so libraries loaded: the original one and an injected SO file with the same name. The injected file was clearly malicious. The main binary was patched in a few places, and the function table into libfsalvfs.so as replaced with the alternate libfsalvfs.so. The alternate file was compiled from NFS-ganesha sources, but modified to include new and improved (wink wink) functionality.

The most interesting of the new functionality were two separate implementations of covert channels.

The first one we encountered already:

- When an open request comes in with 'open-id' instead of 'open id', the file handle is marked. This change is opaque to the NFS server, so unpatched servers just ignore it and nothing much happens.

- For infiltrated NFS server, when the file handle opened this way is read, the NFS server appends the last block with a payload coming from the malware's runtime storage, and the 'eof' on-the-wire value is changed to be the new total size. An unpatched kernel (which shouldn’t really happen, since it marked the file in the first place) will just ignore the extra bytes. The EOF value is used as a bool, e.g. checked for 0 or not and not a specific value, so having a large integer values doesn’t change anything in the flow of an unmodified kernel.

The second covert channel is used for command and control, and is implemented in the VFS code as a fake directory.

Any writes to /<export>/.snapshot/meta/<cmdid> are handled by the malware code and not passed on to the FS. They are pseudo-files that implement commands through read and write operations.

The malware implemented the following commands:

- 1701 - self destruct

- 1702 - set auto self destruct time

- 1703 - run shell command

- 1704 - load SO file from buffer specified in command

- 1706 - get basic system description

- 1707 - get network connections

- 170A - upgrade to new SO file

- 74201 - put buffer in memory dict by ID

- 74202 - get buffer from memory dict by ID

- 74650 - put a payload in memory for the first covert channel

- 74651 - arm the first covert channel

- 74652 - disarm the first covert channel

For example cp payload.so /mnt/server/.snapshot/meta/1704 will load the SO file in the NFS ganesha process on the target server, and echo 1616580589 > /mnt/server/.snapshot/meta/1702 will set an autodestruct time. Reading this file will retrieve the time.

The self destruct command (0x1701) is very interesting - it sends a UDP broadcast on port 41701 with a random payload of size 321 bytes, and then restarts a clean NFS-ganesha. I guess this is some kind of network signalling.

It appears the malware has a watchdog that iterates over all /proc/<pid>/fd/* links every 25ms, and if a link is open to /proc/<malware pid>/maps or /proc/<malware pid>/smaps or /proc/<malware pid>/mem it:

- kills the offending process,

- deletes any writeable file handle it had opened (before it was killed) in

/proc/<pid>/fd/, first trying to wipe it, - calls the self destruct command (0x1701).

Further forensics

Lets go back to that awful Saturday I triggered the self-destruct. Having a faint understanding I triggered something (that being before I reversed the devil) I asked Klaus to disconnect all the network connections to the outer world and we started taking memory dumps of whatever we could, storing them all on the laptop. In hindsight we destroyed quiet a bit of evidence by triggering more self destructs in other subnets, but I think the self destruct signal has already gone out to the bad guys through a different piece of malware that I later partially recovered, and probably "heard" the UDP distress signal (that's what is was called in the binary, not my naming).

After getting all the forensics the client insisted on reconnecting his systems to the web, they were "losing money". I switched from forensics to reversing. In the process, while inspecting the malicious libfsalvfs.so I discovered the commands I mentioned above, and discovered a "feature" that helped me fill more paces of the puzzle.

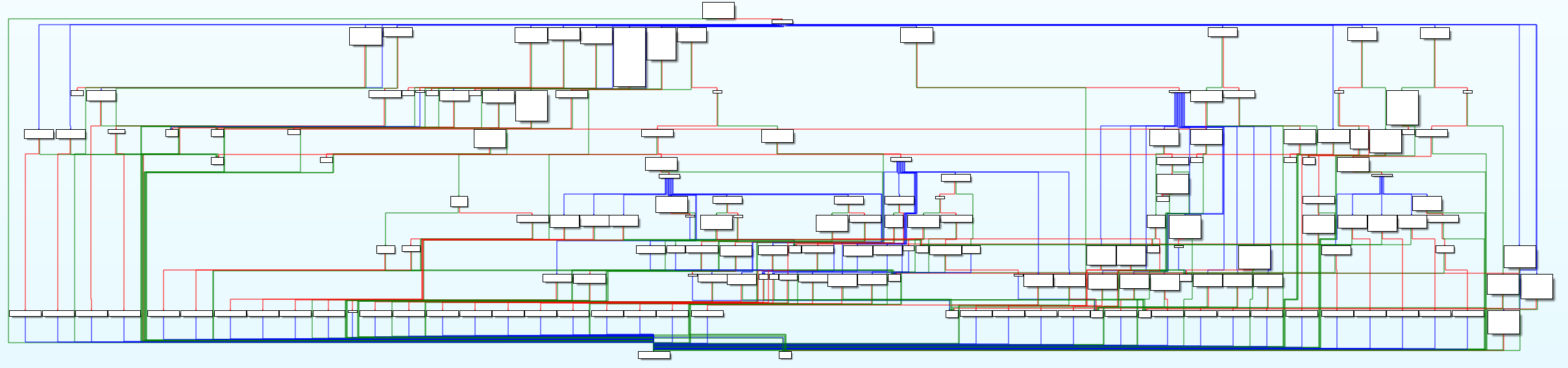

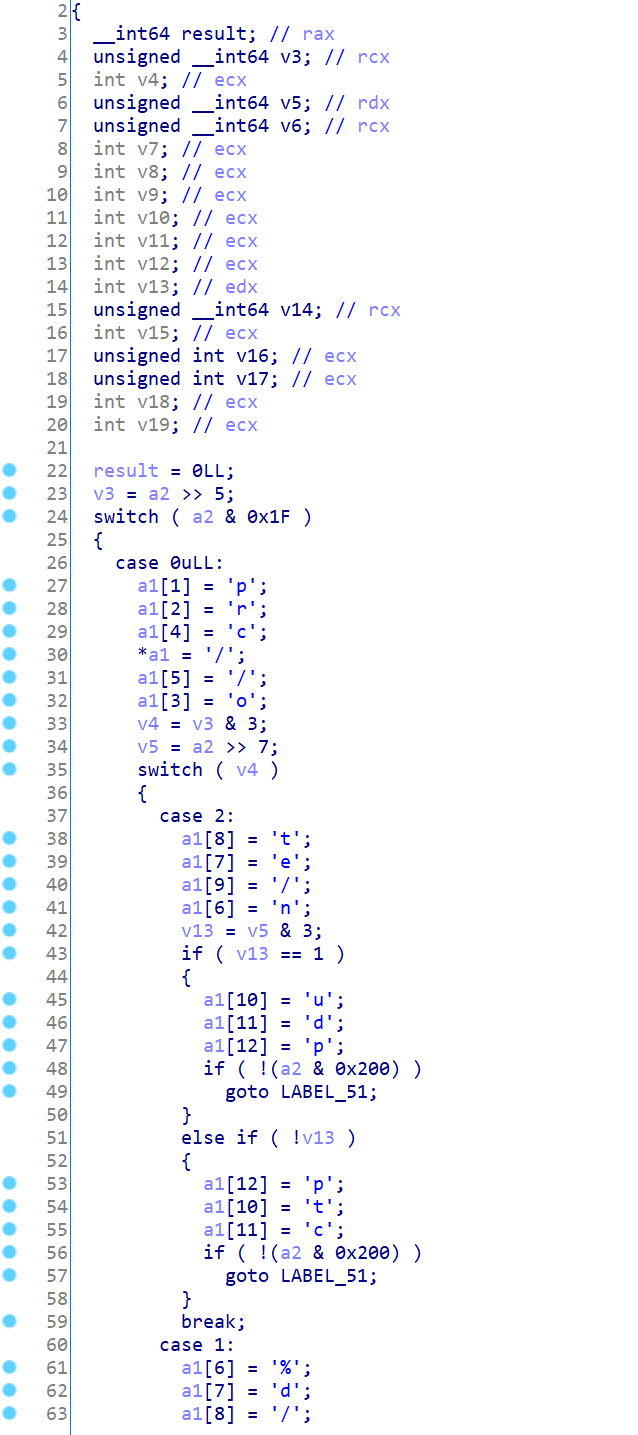

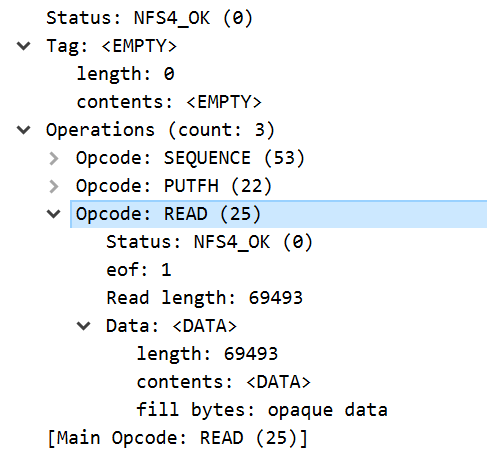

Reversing malware you always find some feeble attempt to obfuscate string using XOR or RC4, or just scrambling the letter ordering. In this case I pretty quickly found a function I called get_obfuscated_string(buffer, string_id). The difference however, was that this one was just horrendous, practically irreversible:

It had like a billion nested switches:

I think they let some intern fresh out of college write that one. It seems the complete list of strings used by the tool are encoded inside in a tree of nested switches, with a variable length encoding, e.g. in one branch the 2nd level might have 3 bits and in another it might have 5 and in a third only a single bit. Some kind of prefix tree if I remember anything from Uni.

Eventually I managed to write code to just brute force the function:

#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <sys/mman.h> #include <sys/types.h> #include <sys/stat.h> #include <fcntl.h> #include <unistd.h> #include <string> #include <set>int main(int argc, char* argv[])

{

// error handling code omitted

const char* filename = (argc > 1) ? argv[1] : “reconstructed.elf”;

unsigned long offset = (argc > 1) ? strtol(argv[2], NULL, 16) : 0x22a0;int fd = open(filename, O_RDONLY); struct stat stbuf; fstat(fd, &stbuf); const char* addr = (char*)mmap(NULL, stbuf.st_size, PROT_READ | PROT_EXEC, MAP_PRIVATE, fd, 0); close(fd); const char* base = addr + offset; typedef int (*entry_t)(char* outbuf, int id); entry_t entry = (entry_t)base; std::set<std::string> found; char buffer[1024]; for(long bits = 1; bits < 64; ++ bits) { bool any_new = false; for(long id = (bits == 1) ? 0 : (1 << (bits - 1)); id < (1<<bits); ++ id) { int status = entry(buffer, id); if(status == 0) continue; if(found.find(buffer) != found.end()) continue; found.insert(buffer); printf("Got '%s'! [0x%x]\n", buffer, id); any_new = true; } if(!any_new) break; } return 0;

}

This first binary had the following strings (I am keeping 3 to myself as they have client related info):

'/proc/self/mem',

'/proc/self/maps',

'/proc/self/cwd',

'/proc/self/environ',

'/proc/self/fd/%d',

'/proc/self/fdinfo/%d',

'/proc/self/limits',

'/proc/self/cgroup',

'/proc/self/exe',

'/proc/self/cmdline',

'/proc/self/mounts',

'/proc/self/smaps',

'/proc/self/stat',

'/proc/%d/mem',

'/proc/%d/maps',

'/proc/%d/cwd',

'/proc/%d/environ',

'/proc/%d/fd/%d',

'/proc/%d/fdinfo/%d',

'/proc/%d/limits',

'/proc/%d/cgroup',

'/proc/%d/exe',

'/proc/%d/cmdline',

'/proc/%d/mounts',

'/proc/%d/smaps',

'/proc/%d/stat',

'nfs',

'nfs4',

'tmpfs',

'devtmpfs',

'procfs',

'sysfs',

'WSL2',

'/etc/os-release',

'/etc/passwd',

'/etc/lsb-release',

'/etc/debian_version',

'/etc/redhat-release',

'/home/%s/.ssh',

'/var/log/wtmp',

'/var/log/syslog',

'/var/log/auth.log',

'/var/log/cron.log',

'/var/log/syslog.log',

'/etc/netplan/*.yaml',

'/etc/yp.conf',

'/var/yp/binding/',

'/etc/krb5.conf',

'/var/kerberos/krb5kdc/kdc.conf',

'/var/log/ganesha.log',

'/etc/ganesha/ganesha.conf',

'/etc/ganesha/exports',

'/etc/exports',

'Error: init failed',

'DELL',

'/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libnfs.so.4',

'/tmp/.Test-unix/.fa76c5adb8c04239ff3034106842773b',

'Error: config missing',

'Error: sysdep missing',

'Running',

'LOG',

'/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/ganesha/libfsalvfs.so',

'none',

'/etc/sudoers',

'/proc/net/tcp',

'/proc/net/udp',

'/etc/selinux/config',

'libdl.so.2',

'libc-',

'.so',

'cluster-config',

'recovery-signal',

Eureka Moment

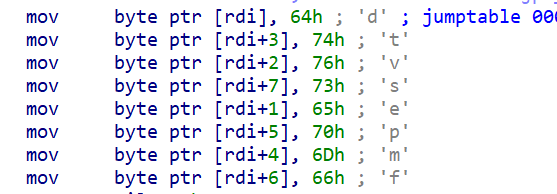

Staring endlessly at this weird function I thought to myself: maybe I can look for code that is structured like this in all the dumps we obtained. We have all those block of mov byte ptr [rdi+?], '?':

So lets look for blocks of code that are highly dense with these opcodes:

import syswith open(sys.argv[1], ‘rb’) as f:

data = f.read()

STATE=None

for i in range(len(data) - 6):

if ord(data[i]) == 0xc6 and ord(data[i + 1]) == 0x47:

if STATE and (STATE[0] + STATE[1] + 0x40) >= i:

STATE[1] = i - STATE[0]

STATE[2] += 1

else:

if STATE and STATE[2] >= 20:

print(‘Found region at 0x%x - 0x%x’ % (STATE[0], STATE[0] + STATE[1]))

STATE = [i, 4, 1]

And I found them. Oh I did. Some adjustment even led to a version for ARM systems:

The GOlang thingy

I finally found the payload that was sent over to the GW machines. It had 2 stages: the first was the 8192 buffer loaded through the first covert channel. The kernel was modified to inject this buffer into the GOlang application and hook it. This will get fairly technical, but I enjoyed it and so will you:

- First note that in the Golang stdlib an HTTP connection can be read through the

net/http.(connReader).Readfunction. The calls are made through aio.Readerinterface, so the calls are made through a virtual table, and the call locations cannot be statically identified. - the kernel inject begins by allocating a bunch of RWX memory immediately after the GOlang binary - let's call it the trampoline area, and it will include two types of generated trampoline functions,

- Next the ELF symbol table was used to find the 'net/http.(*connReader).Read' symbol,

- What we’ll call the 1st trampoline function (code below) is copied to the trampoline area, patching the area marked with

HEREwith the first 9 bytes ofnet/http.(\*connReader).Read mprotect(net_http_connReader_read & ~0xfff, 8192, PROT_EXEC | PROT_READ | PROT_WRITE)- modified the beginning of

net/http.(\*connReader).Readto a near jump into the trampoline - using 5 bytes of the 9 original used by 'move rcx, fs:….' that are the preamble to function.

First trampoline function

pop rax

pop rcx

push rcx

push rax

mov r11, cs:qword_<relocated>

mov rdi, rcx

call qword ptr [r11+8]

pop rax

pop rcx

push rcx

mov rcx, fs:0FFFFFFFFFFFFFFF8h <---- HERE

cmp rsp, [rcx+10h]

jmp rax

- When the trampoline is called (from the new near jump in the beginning of

net/http.(*connReader).Read) it examines the stack to locate the return address, and checks if a second type of trampoline we'll refer to as the return trampoline has already been allocated for the return address for the function, - If not it allocates a new trampoline per call location of

net/http.(*connReader).Readfrom the code below, replacing 123456789ABCDEFh with the absolute address of a function in the malware, - GOlang uses memory for all function argument passing, so immediately after the virtual function call to

Read()there will always be a 5 bytemov reg, [rsp+?]to loadRead()'s result into a register. Thismovinstruction is copied into the firstdb 5 dup(0)area, - those same 5 bytes are then replacing with a near jump to the 2nd trampoline

- the 2nd db 5 dup(0) are filled with a relative near

jmpback to the original code patch site.mov rax, 123456789ABCDEFh mov rdi, rsp call rax db 5 dup(0) db 5 dup(0)

This way eventually all the net/http.(*connReader).Read call sites are patched to call a function immediatly after net/http.(*connReader).Read virtual call returns. This lets the malicous code inspect the decoded HTTP packet.

On initialization the 1st stage malware also loads the hefty 2nd stage through the 2nd covert channel, and passes each buffer received from the patch on net/http.(*connReader).Read to it for inspection.

The data collected is collected and compressed by the malware and stored back to the NFS server (the 2nd covert channel which bypasses read ACLs on NFS).

Before this case I did not think there was any nice way to hook random GO binaries, this technique is pretty cool.

Unfortunatly I cannot discuss what the 2nd payload actually as it will reveal stuff my employer isn't ready for yet.

How the kernel got patched? and why not the golang app?

The golang app is built inside the CI/CD network segment. This segment can only be accessed through monitored jump hosts with MFA. Each day, the CI/CD pipline clones the source code from the GIT server, builds it, and automatically tests it in a pre-production segment. Once tested it gets digitally signed and uploaded to the NFS server. The running app self updates, checking the digital signature beforehand.

The kernel, on the other hand, is manually built by the guy responsible for it on his own laptop. He then digitally signs it and stores it on a server where it is used by the CI/CD pipeline. Fortunatly for us a commented out line in a script in the CI/CD pipline (a line that was not commented out in the GIT!) did not delete old versions of the kernel and we know which versions were tampered with.

We noticed a 3 month gap about 5 month ago, and it corresponded with the guy moving the kernel build from a Linux laptop to a new Windows laptop with a VirtualBox VM in it for compiling the kernel. It looks as if it took the attackers three months to gain access back into the box and into the VM build.

What we have so far

We found a bunch of malware sitting in the network collecting PII information from incoming HTTPS connection after they are decoded in a GOlang app. The data is exfiltrated through the malware network and eventually is sent to the bad guys. We have more info but I am still working on it, expect another blog post in the future with more details, samples, etc’.

Q&A

-

Q: What was the initial access vector?

<p><strong>A</strong>: We have a pretty good idea, but I cannot publish it yet (RD and stuff). Stay tuned!</p> -

Q: Why didn't you upload anything to VT yet?

<p><strong>A</strong>: A few reasons:</p> <ul> <li>I need to make sure no client info is in the binaries - some of the binaries have hardcoded strings that cannot be shared</li> <li>All of the binaries I have have been reconstructed from memory dumps, so are not in their original form. Does anyone know how to upload partial dumps into VT?</li> </ul> -

Q: It there a security vulnerability in GO? in the Kernel?

<p><strong>A</strong>: Defenitly not! this is just an obnoxious attacker doing what obnoxious attacker do. I might even say the complexity of the stuff means they don’t have a 0day for this platform.</p> -

Q: What about YARA rules, C2 address, etc'?

<p><strong>A</strong>: Wait for it, there is a lot more coming!</p> -

Q: Why did you publish instead of collecting more?

<p><strong>A</strong>: To quote the client "I don't care who else they are attacking. I just want them off my lawn!", and he thinks publishing will prevent them from returning to <strong>THIS</strong> network.Hopefully what we publish next time will get them off other people’s lawns.

-

Q: Any Windows malware?

<p><strong>A</strong>: Definitly, including what we believe is an EDR bypass. Still working on it.</p> -

Q: Any zero days?

<p><strong>A</strong>: Maybe …</p> -

Q: Who are these bad guys you keep refering to?

<p><strong>A</strong>: No clue. Didn’t find anything similiar published. There is now sure way to make anything except unsubstantiated guesses, and I won’t do that.</p>

To be continued.

Article Link: https://igor-blue.github.io/2021/03/24/apt1.html